“My policies are based not on some economics theory, but on things I and millions like me were brought up with: an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay; live within your means; put by a nest egg for a rainy day; pay your bills on time; support the police.” – Margaret Thatcher, 1981

Today, many people around the world will be mourning the passing of one of Britain’s most distinctive and most divisive post-war prime ministers. Margaret Thatcher’s economic reforms were lauded by many as having rescued the country from the economic malaise of the 1970s and denounced by others who saw her as out to crush the labor union movement.

Of course both narratives contain some element of truth, but could politicians today, struggling in the wake of the Great Recession learn anything from the Thatcher era?

The 1970s was characterized by a cascade of economic crises from the collapse of Bretton Woods and the 1973 oil shock to the infamous “winter of discontent.” It was also marked by a sharp deterioration in relations between the labor unions and government that saw widespread strikes, electricity cuts, and the three-day working week.

When Thatcher came to office in May 1979, she did so with the stated aim of curing the “British disease.” In practice, this meant a series of radical reforms including the privatization of state-owned industries and the unwinding of the statutory underpinning of the union power, which set her on a direct collision course with the unions.

Undoubtedly, these reforms have left a permanent imprint on British society. At the time Thatcher took office, over 50% of the working population were members of trade unions. By the early noughties this figure had dropped to below 30%, and in the private sector the figure was less than 20%.

A number of economists have argued that reducing the wage-fixing powers of the unions was necessary to break the cycle of high inflation leading to higher wages, which in turn pushed prices up even further. As Stephen Nickell, economist and former member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, put it in a 2001 speech at the Society of Business Economists:

[Whatever] these changes have meant for the working conditions of the average employee, there seems no question that they have contributed to the decline in inflationary pressure at given levels of labour market slack and hence to the fall in…unemployment.

Given that the UK has been suffering from above target inflation for majority of the past five years, since the onset of the financial crisis, commentators might be forgiven for drawing parallels with the 1970s. Yet this ignores some crucial differences.

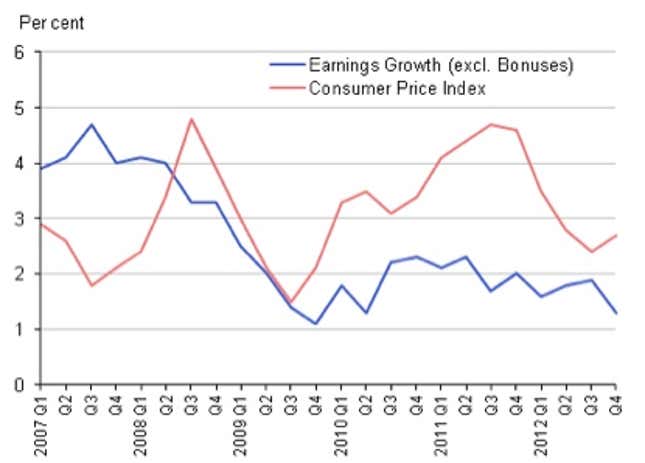

Below is a chart from the Office for National Statistics showing the behavior of wages and inflation over the crisis:

As this illustrates, wage growth has not been contributing to Britain’s inflation problem. In fact quite the reverse, real wages have been falling consistently since the second quarter of 2008.

Far from the situation that confronted the Conservative party in 1979, today’s Coalition government is having to deal with a new phenomenon of rising employment coupled with falling productivity. Though there are many potential explanations for this so-called “productivity puzzle,” it is highly unlikely that this situation reflects an inflexible labor market.

Indeed Simon Wren-Lewis, economics professor at Oxford University, suggests that part of this puzzle could be explained by a remarkable flexibility of UK workers:

This leads to one possible story: factor substitution. Firms are replacing machines by workers, because real wages are low. Real wages are low because the UK labour market has become more flexible, and workers are cutting wages in response to unemployment by more than they used to.

So could another round of Thatcher’s labor reforms and privatizations help spur the British economy out of its current slump? Probably not.

While private sector investment was very possibly being restrained by the wage demands of workers in the 1970s, non-financial corporations on both sides of the Atlantic are sitting on large cash reserves. Their unwillingness to invest suggests either a dearth of opportunities or a paralyzing fear of further economic weakness to come, or possibly both.

Either way, those suggesting a repeat of the Iron Lady’s approach to economic policy offers a panacea might do well to recall a quote from another great 20th Century figure, John Maynard Keynes:

Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.