A few years back, I was talking to one of the smartest finance people I know. It was wasn’t long after the crisis, the economy was pretty much a smoldering crater. Everyone’s ears were ringing.

Anyway, he was explaining to me why the Federal Reserve’s efforts entice people to borrow more by pushing interest rates lower and lower wasn’t going to result in the kind of refinancing and home-buying boom we had come to expect when the Fed cut rates.

The Fed was basically trying to sell booze at an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, he explained.

“It doesn’t matter how low the price is,” he said. “These people just don’t drink anymore.”

It’s a crude metaphor, sure. And it doesn’t take into account that much of the Fed’s efforts to push low rates through a deeply damaged financial system made it more like a liquor wholesaler cutting prices, and hoping they filter through the mark-ups at badly run bar.

Still, his explanation rang true. Low interest rates weren’t going to generate a boom. And they haven’t. Yet.

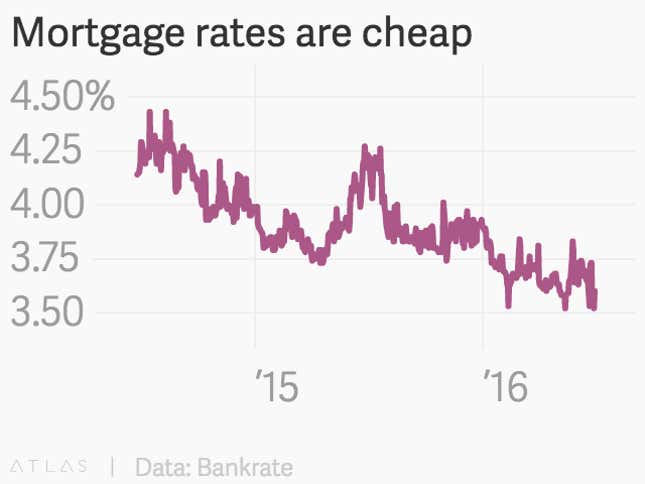

That could be about to change. The weak US jobs report in May, and more recently the Brexit shock, pushed boatloads of cash into the safety of US government bonds, pushing interest rates—and the mortgage rates that track them—to some of their lowest levels in the last two years.

Those happy-hour prices might be tempting people back to take a tipple. Over the last year, the Mortgage Bankers Association index of applications for new home purchase has been running an average of more than 20% higher than the prior year. After flatlining for years, US credit card debt outstanding is growing at its fastest clip since the financial crisis. In April it was up roughly 5.5%, compared to the prior year.

Consumers are in much better financial shape then they were during Great Recession and for a long time after it, when unemployment declined painfully slowly. Now, the percentage of Americans with low, or “subprime,” credit scores has fallen to its lowest level in a decade, according to a recent article in the Wall Street Journal. Given that they’re far more creditworthy, banks and financial institutions are more likely to lend to them.

Speaking at a conference earlier this week, the CFO of Wells Fargo, one of the country’s largest mortgage lenders had this to say:

“In mortgage, it’s a stronger year this year versus last year. Affordability in many places still remains good. Rates are down. So, mortgage-ability and financing costs are still very attractive. There’s more supply, more people have jobs. So, that is a – it’s a better business. It’s a brisker business.”

Given that credit is the gasoline in the US economic engine, this is a very good thing.

In other words, don’t fall into the trap of thinking that just because low interest rates didn’t provide much pep to the world’s largest economy in 2011, they won’t generate results today.