Xenophobic. Racist. Jingoistic. Nativist. Parochial. The 52% of British voters who hit the EU eject button might be all of those things. But they were also backing the right horse.

The vote repudiates a vision of Europe that rewards companies at workers’ expense. It’s a rebuke of a government that invests authority in a professional elite insulated from the economic realities of ordinary Europeans. The free flow of goods, services, capital, and people within the EU was supposed to spread prosperity. It hasn’t. Eventually, something big had to break.

While Brexit is certainly big, the fissure beneath it is bigger than Britain, or even Europe. The imbalances of trade, capital, labor, and—above all—savings that lie at the heart of Europe’s current turmoil warp the entire global financial system. Nearly everywhere you look, growth is sputtering because there’s simply too little demand—and far too much debt—to go around. And that’s thanks in no small part to the EU’s wooly-headed policies. However painful it might make the next few months or years, Brexit might ultimately be the wake-up call that prevents the EU from unleashing another global financial crisis, and condemning the world to decades of feeble growth.

To understand why things have gotten to this point, we have to examine the fundamental flaws in the EU’s design that are largely responsible for these distortions.

The curse of the euro

The EU—or more specifically, the euro zone—suffers two major flaws: its common currency and its lack of a central fiscal authority. Both, argues Steve Keen, economics professor at Kingston University, make it next to impossible for the EU to ever heal its most broken economies—Greece, Spain, Italy, and Portugal.

The first problem is that 19 countries share a common currency, the euro, despite yawning disparities among these members’ trade competitiveness. Those nations that can’t boost their exports sufficiently are unable to let their currency depreciate in response to market demand. That leaves them persistently unable to compete globally.

This is compounded by the second problem: The lack of a continental treasury to compensate for a region’s economic weakness. Consider a federation of states that actually works—the United States. Alabama has a weaker private sector than many other states, and likely runs a trade deficit with them. But the US federal government doesn’t demand Alabama live within its more constricted means. By collecting and redistributing taxes, the federal government can rebalance wealth disparities among its states. It shifts some of the taxes it draws from other states to Alabama, and keeps the Alabama economy humming. The EU can’t do that. It can’t offset individual countries’ deficits because it lacks a central treasury.

There is a third huge flaw in the EU that’s not a structural issue, but rather stems from its leaders’ fanatical refusal to let governments run deficits. This is both ideological—based on a misguided yet deep-rooted faith in neoliberal economics—and bureaucratically ordained. A section of the EU’s founding Maastricht Treaty forbids member governments from running a budget deficit greater than 3% of GDP, and limits government debt to 60% of GDP. While in the past these limits had been disregarded often enough, since the 2008 global financial crisis, they’ve formed the basis of the EU’s austerity policies. Meanwhile, the paramount responsibility of the European Central Bank is maintaining “price stability.” Employment is but of ancillary concern.

What happens when you put all these elements together?

In the first half-decade of this century, not much. ”The European system worked well when times were good,” says Peter Temin, economics professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “But the policy response to 2008 was terrible.”

Member countries mired in economic depressions have but a single lever—their own taxation system—to revive their economies. Since they can’t devalue their currency, when member countries find themselves struggling to compete, they can’t revive exports. Sales fall and tax revenue suffers. Layoffs drag down consumption. And debt grows faster than their ability to pay it. The austerity necessary to bring budgets back towards balance dampens demand even more, and the cycle repeats. As economic conditions worsen, many residents flee to other countries to make a living, leaving their home economy to implode.

It’s not that no one anticipated this. Keen points to an article that economist Wynne Godley wrote in 1992, in which he augured the disaster these flaws would wreak on Europe:

If a country or region has no power to devalue, and if it is not the beneficiary of a system of fiscal equalisation, then there is nothing to stop it suffering a process of cumulative and terminal decline leading, in the end, to emigration as the only alternative to poverty or starvation.

In continental Europe, that’s obviously come to pass—and many in Britain feel they’re bearing the brunt.

The UK obviously isn’t in the euro zone (a fact that has both allowed its economy to recover more quickly and makes it easier for Britain to leave the EU). However, its relationship with the EU leaves Britain vulnerable to the perilous imbalances created by the euro zone’s reckless design. Though subtler than inflows of foreign workers, the trade and capital imbalances wrought by Germany’s decades-long refusal to restore balance to the euro zone—a policy that gave rise to the European wave of financial crises—has hurt Britain too.

Blame Germany

The reunification of east and west Germany in the early 1990s plunged the country into a period of high unemployment and sluggish growth. To create jobs, German exports had to become more competitive. So the government, unions, and business owners negotiated a suite of policies designed to cap wages and ratchet up production. This shifted profits from workers to company owners, leaving more and more wealth in corporate bank accounts instead of the German people’s pockets. Since companies ultimately spend less than people do, national savings rose, exceeding investment.

These policies were still in place when Germany and a dozen or so other countries swapped their currencies for the euro, forming the euro zone. Suddenly, Germany had a huge market with a common currency to trade with, turbo-charging its exports. Even as German GDP picked up, wage growth remained capped, allowing its businesses to price goods cheaply and outcompete other countries’ exporters. That swelled Germany’s current account surplus, a term economists use to describe a country’s extra trade earnings (and, conversely, the extra investment they send flowing abroad).

Trade and capital flows must balance each other out. So when one country runs a chronic current account surplus, others must run deficits, importing more than they export. That’s what happened in the other euro zone countries as they absorbed cheap German goods that German consumers were unable to consume.

When we talk about current account balances we often use them as a stand-in for trade balances. But there’s another way of thinking about it that illuminates how consumption, savings and investment in one country affects others—and therefore, how policies that change people’s willingness to consume force people in other countries to consume differently too, whether they realize it or not. Germany’s current account surplus means it was saving more than it was investing. Those savings—or capital—had to be invested somewhere.

And this makes sense; the country on the other side of that equation, that’s running a current account deficit, is basically earning less from its own exports than it’s spending buying imports. It pays for those extra imports by borrowing from other countries.

Running a current account deficit is fine as long as it’s temporary, or as long as the country’s debt is growing more slowly than its economy. What makes chronic trade deficits unsustainable, however, is the debt required to maintain them.

For example, in the early 2000s, Spain had a pretty healthy economy; it was running a budget surplus and had some of the region’s strictest banking laws. It also had enough capital that its firms had no trouble borrowing to expand their businesses. It didn’t need more capital. But more capital it got—flooding in from Germany. That inflow gushed into Spain’s property market. Home prices climbed, leaving Spanish households feeling wealthier. They bought furniture and electronics to outfit their new homes, and cars to put in their garages.

Owning bigger, fancier homes, however, didn’t boost Spanish workers’ incomes to help them pay back their growing debts. In fact, despite the temporary economic bump from the construction boom, they were less able to. Surging inflation made Spanish goods even less competitive. But since it belonged in the euro zone—and therefore couldn’t devalue—Spain could neither deflate its property bubble nor counteract inflation.

Disparities deepened: As spending drove inflation, Spanish purchasing power continued to rise, while that of under-consuming Germany slumped. Spain became steadily less competitive. This chart shows the real increase in labor costs relative to 1999:

By the time the financial crisis hit in 2007 and 2008, the borrowing-fueled Spanish housing bubble was huge—and its imbalances with Germany had eroded its ability to pay its debts.

When the bubble finally burst, billions of euros in wealth vanished with it. Unemployment soared. Spain was swamped in debt, a state in which it remains still today. It also left Spain and its fellow debt-laden euro zone brethren unable to continue buying Germany’s extra goods.

So which foreign countries are currently stuck with absorbing Germany’s excess? Well, the UK, for one.

How euro zone imbalances hurt the UK

Of course, Britons have their leaders to blame for most of their economic woes. But not all of them—the UK’s gaping current account deficit, for example. Since the financial crisis, the stalactite-like formation that is the UK’s current account deficit continues to grow, hitting 7% of the UK’s GDP in the first quarter of 2016.

Britain’s biggest trading partner is the EU. In 2015, Britain accounted for nearly two-fifths of the euro zone’s surplus in exports of goods and services, according to Eurostat data. That has helped bump up the euro zone’s current account surplus to 3.2% of its GDP in 2015, up from 2.5% the year before.

And as you can see, Britain’s relationship with its European trade partners is far from reciprocal. In fact, Britain buys more euro zone goods and services than those of any other country—and sells relatively much less in return. That’s not the case in its trading relationship with the rest of the world:

When things get rough on the continent, Brits, it seems, become Europe’s consumers of last resort.

Buying more from abroad than it sells has put its own exporters out of work (mostly in manufacturing). And as the UK’s current account deficit has deepened, first consumers, then the government have borrowed to keep demand aloft.

Of course, you need some sum of debt to keep factories expanding and entrepreneurial activity in bloom. But when lending is going largely to fund consumption—including home purchases—it’s not boosting earnings in a way that ensures those debts will be paid.

The more the euro zone forces its own imbalances on the UK—instead of stoking its own internal demand—the more Britons will have to borrow. And as Spain and its southern European neighbors discovered, when the debt burden grows big enough, lenders start cinching their purse strings, and the spending must end. It leaves the UK in danger of relapsing into the kind of financial catastrophe we saw in 2008.

“The scariest graph in the world”

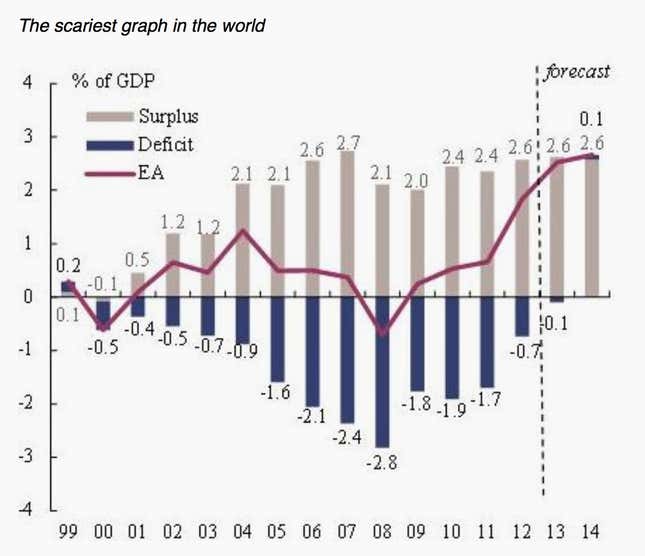

This isn’t necessarily accidental. Back in 2013, Michael Pettis, finance professor at Peking University, hailed what he called the “the scariest graph in the world.”

Recall that before the financial crisis, peripheral European countries imported Germany’s exports, their deepening deficits balancing out their Teutonic neighbor’s soaring surpluses. Obviously, southern Europe can no longer afford to absorb Germany’s excess production. But the plan isn’t to halt the export bonanza. The chart in question, presented by EU economists in Pettis’ class at Peking U, shows a plan to force Europe’s surpluses, to countries outside the euro zone.

“In a world with weak demand and deteriorating trade relationships… the northern Europeans have decided that rather than boost domestic demand they will resolve their domestic problems by absorbing far more than their share of global demand, to the tune of 2-3% of Europe’s GDP,” wrote Pettis at the time. (In this chart, the columns show surplus and deficit as a share of GDP; “EA” refers to the euro zone current account balance as a share of GDP.)

Here’s what has happened since:

We checked back in with Pettis about what has subsequently come to pass. ”Remember what I said at the time—that it was impossible for what actually has happened to happen? What we’ve seen in the last two to three years, I said way back then, ‘No way could that happen—it would be too damned irresponsible of Germany,'” he says. “Well, I was wrong.”

Gobbling up global demand

By quashing consumption in the euro zone, austerity has also pushed down the UK’s savings rate.

Ironically, if the UK government does the right thing and launches a fiscal stimulus—temporarily spending to prevent its economy from tanking—it winds up essentially borrowing from its future taxpayers to buy Europe’s austerity-driven exports.

The way to squeeze European distortions back into balance, then, would be to force Germany to boost spending and kick up inflation—and restructure debt so that Spain and other debt-laden countries have a real shot at eventually making good on what they owe. Rampant unemployment and unused factory capacity in southern Europe suggest fiscal stimulus could help juice growth—boosting demand overall.

But restructuring debt would force losses on creditors, and fiscal stimulus would require more government borrowing, anathema to the EU’s anti-deficit dogma. Instead the plan is to grow out from under the debt by forcing indebted governments to cut spending and collect more taxes.

This is a big gamble. Austerity might limit debt, but it doesn’t create growth. And the longer it takes to deleverage, the more austerity gnaws away at their long-term potential to grow. Even if it succeeds in preventing a sovereign debt crisis, the euro zone’s imbalanced growth leaves the global economy at risk of another financial crisis.

The tragedy of austerity

For the many people horrified by the ”leave” vote and all it appears to stand for, it might help to remember what EU and British leaders consistently haven’t stood for: their people—working people in particular. The problems that have sparked anti-EU antipathy seem unlikely to have occurred if the euro zone and Britain had let the economic needs of ordinary households—and not the abstract anxieties about sovereign credit—guide their policies.

“The whole European project was a neoliberal economic agenda sold to workers like castor oil: ‘You’re not going to like the taste but it’s good for you,'” says Keen. “Well, it tastes bad and it’s been dreadful for us.”

“What globalization has meant for the working class is deindustrialization, falling wages, disappearing jobs. Reducing the size of the public sector, [limiting] union, enabling capital movement—all this stuff is supposed to lead to economic nirvana. ‘You’ll be working in the service sector but it’ll be higher paid,'” he adds. “The elite is still selling this message because the elite do very well out of this. It’s the working class being screwed.”

The tragedy isn’t merely one of injustice for workers, though. It’s also breathtakingly destructive economics. Policies like the EU’s that leave households and governments boxstepping between debt and unemployment ultimately benefit creditors, banks, and big business owners. As this tiny, privileged segment of the global economy vacuums up more and more middle-class wealth, it sucks up consumer demand—the engine of global economic growth—along with it.

That’s why when you shift wealth to the captains of capital, economies stagnate. This might seem obvious—tautological, even. But, strangely, even after the world’s financial and bureaucratic elite already let these dangerous imbalances plunge the world into a global financial crisis, they seem bent on inviting another.

Brexit: Hope for change?

What now?

The most likely arrangement post-Brexit is for the UK to adopt a Canadian-style trade agreement with the EU, giving it access to the single market. However, that won’t cover banking and financial services, which make up an astonishing share of the UK’s exports.

Even if weaning Britain off its reliance on its hypertrophied banking system ultimately makes the economy more stable, it’s bound to be excruciating.

“Brexit, unless they walk it back, will harm the English economy, grievously harm the City of London, and may break up the UK as a whole,” says MIT’s Temin. “The referendum has destabilized the EU, which already is suffering from bad policies after the collapse of 2008.”

Then again, if the world is to avoid another catastrophic financial crisis, righting these imbalances has to start somewhere.

With capital gushing out of the UK and the pound at a two-year low against the euro, British manufacturing will have a chance to revive. That will take investment, of course. Rates are hovering at zero everywhere, though, so it shouldn’t be hard for those in genuine need of credit to borrow, says Peking U’s Pettis. If it helps redistribute wealth and diversify the economy, the growth that will follow as manufacturing picks up will be far more sustainable in the long term than if the British economy remained lashed to its financial sector’s fortunes.

Keen does see a glimmer of hope for Europe, though—a chance for a reckoning among EU leaders that they must address the structural flaws in the euro zone’s design in a way that rebuilds the southern European countries’ economies At the very least, says Pettis, the obsession with fiscal zealotry and preserving German competitiveness must end.

“If there is a wakeup call it has to be a recognition that it’s not austerity that’s going to get them out of this,” he says. “Austerity simply means after Germany bankrupts peripheral Europe and can no longer do so, they push their entire surplus abroad. And the US will probably have to absorb it.”

And that would ultimately be catastrophic: Even the US can’t borrow from foreign countries to pay for its imports forever. And when austerity has worn away enough of the global economy’s ability to grow, those debts will bury the world in another financial crisis, maybe even a reprise of the Great Depression.

As part of the EU, Britain was neither empowered nor inclined to lead the major world economies in ending these damaging policies. Maybe going solo will help it find the will to do so now.