Despite the pall of deep and lasting uncertainty cast over the British economy by the electorate’s vote to leave the European Union, British stocks rallied like crazy today (June 30). The FTSE 100 surged roughly 2.3% on the day, bringing the market to a high for the year.

Let’s be clear. The markets are not rallying because Britain’s economic prospects look bright. They’re rallying because things look downright bleak—bleak enough, in fact, for Bank of England governor Mark Carney to make a public statement on behalf of the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street. Here’s the short version.

The prospect of fresh assistance from the central bank sent the pound tumbling and pushed stocks sharply higher. What with all the excitement among traders, few properly digested the full context of Carney’s remarks. He ended the speech—his second since the June 23 vote to leave the EU—with a clear warning that monetary policy likely won’t be enough to keep the economy running strong.

“Monetary policy cannot immediately or fully offset the economic implications of a large, negative shock,” he said. “The future potential of this economy and its implications for jobs, real wages, and wealth are not the gifts of monetary policymakers.”

The predicament Carney lays out is a familiar one for central banks since the 2008 financial crisis and the ensuing global recession. Over and over, politicians have been unable to take the kind concrete steps needed to help shore up economic growth. And in some cases, political actions have threatened to topple a shaky return to growth.

“I think, in general, governments have relied too heavily on central banks,” former Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke told Quartz in an interview last year. “And we’ve therefore had a less vigorous recovery, and a less balanced policy response than we otherwise would have had.”

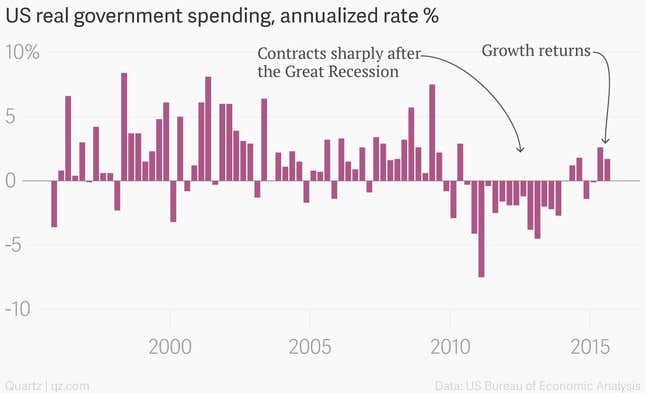

The man knows of which he spoke. In the aftermath of the Great Recession, US government spending—including that of state and local governments—retrenched sharply, supplying another headwind to the painfully slow US recovery.

The story elsewhere has been similar. After the Japanese government tightened fiscal policy in 2014 by raising taxes, the country found itself back in recession, prompting The Bank of Japan to undertake a fresh round of easing that now includes the somewhat experimental and uncertain policy of negative interest rates.

In Europe, endless political dithering over the problems of Greece and other heavily indebted nations has landed much of the continent in a deflationary soup. There seems to be little political appetite for the kind of policy adjustments Europe desperately needs—mainly debt write-downs and greater consumption by Germany. Mario Draghi’s European Central Bank, which is tasked with keeping prices stable, has had little choice but to undertake a wide array of monetary policies, bond purchases and negative interest rates among them, that one would be hard-pressed these days to keep describing as “unconventional.”

And now, egged on by a crop of populist, truth-challenged political figures, Britain has voted to leave the EU, effectively saying they planned to tear up a large share of the trade deals that offer it access to the rich EU single market. Essentially, this was a vote for a sharp recession, a weaker pound, and lower real incomes due to higher prices for imported goods. (The weaker pound pushes up import prices, as it takes more pounds to buy the same amount of stuff from abroad.)

The Bank of England hopes to keep things from getting too ugly. We should wish them luck. It’s a thankless task.

But you can’t help but wonder whether democracies wouldn’t make better economic decisions if central banks weren’t so quick to save them from the consequences of their bad ones.