Positive data on the UK economy don’t totally douse fear of a triple-dip recession

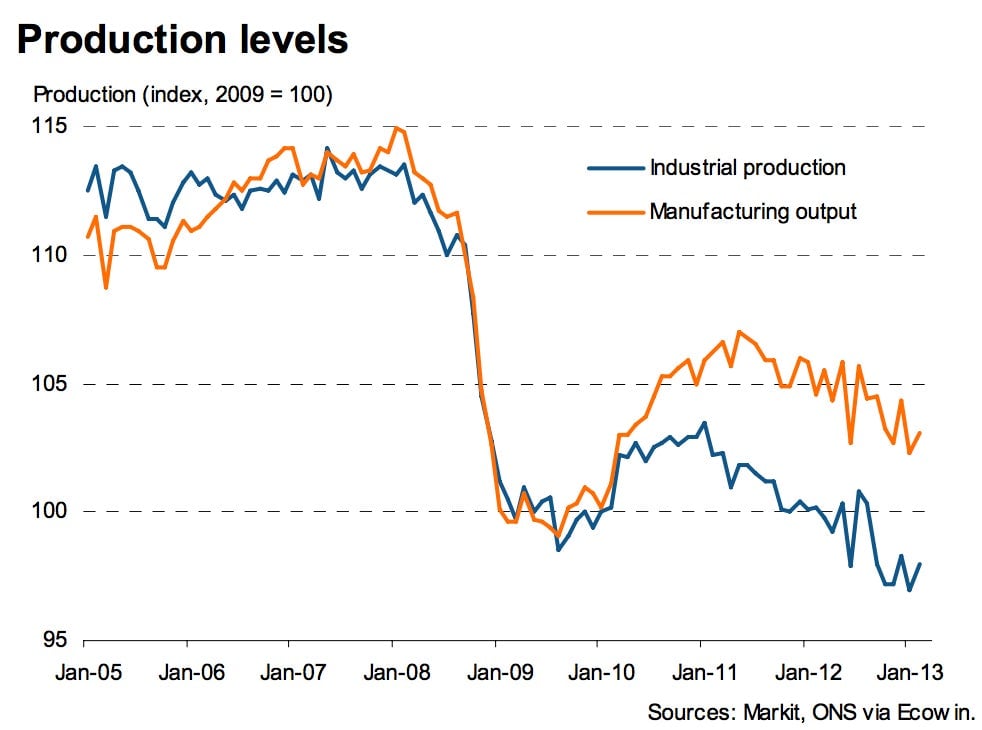

The UK economy saw another dram of possibly good news today, following on last week’s unexpectedly strong UK services PMI data. February industrial production rose 1.o% month-on-month, while manufacturing picked up 0.8% from January. That was way more than analysts expected—and much better than January, when both measures contracted markedly. Because the two combined make up a little more than one-fifth of the UK economy (services contribute around three-quarters of GDP, with a teeny fraction allotted to agriculture), these are critical measures of the UK’s economic health. Here’s how they look in chart form, via Markit:

The UK economy saw another dram of possibly good news today, following on last week’s unexpectedly strong UK services PMI data. February industrial production rose 1.o% month-on-month, while manufacturing picked up 0.8% from January. That was way more than analysts expected—and much better than January, when both measures contracted markedly. Because the two combined make up a little more than one-fifth of the UK economy (services contribute around three-quarters of GDP, with a teeny fraction allotted to agriculture), these are critical measures of the UK’s economic health. Here’s how they look in chart form, via Markit:

But as you can see, these data are really quite erratic. And that’s a reminder that optimism about these figures is at this point little more than a silver-lining reading of the situation. For one thing, the Office for National Statistics slashed its January estimate for manufacturing growth from -1.5% to -1.9%. So that not only means that February’s data is rising off a very low base, but it should also mute confidence in the data themselves.

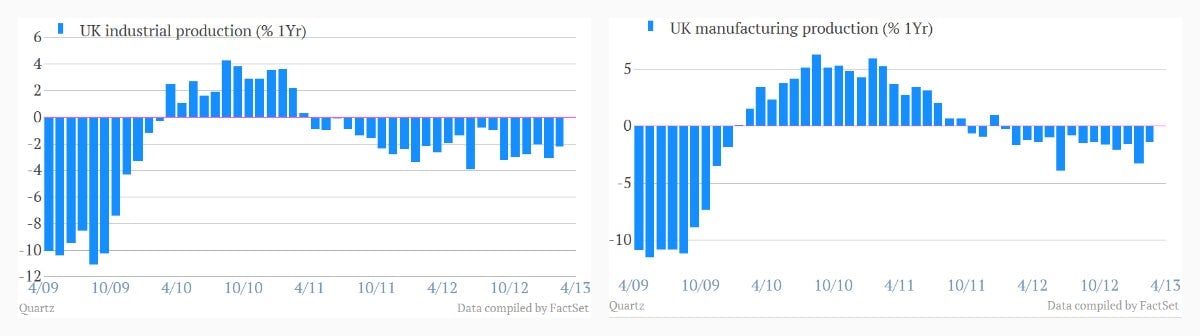

In addition, we’re still looking at year-on-year declines for both measures. While there might be a hint that that’s moderating, that deterioration has been fairly consistent over the last 14 or so months:

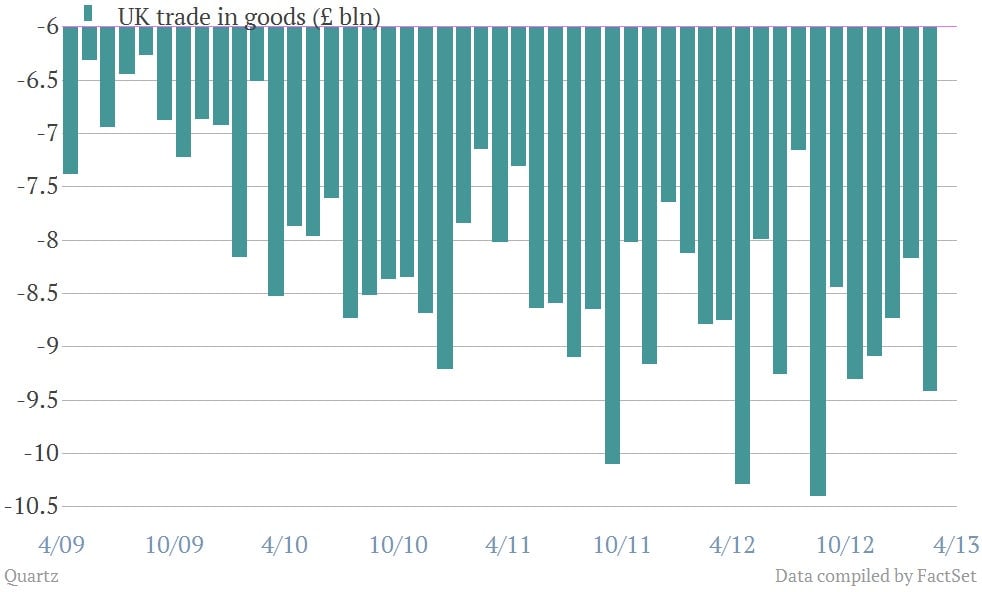

Finally, though, comes UK’s trade balance, which grew to a deficit of £3.6 billion in February, from £2.5 billion in January. The deficit in goods slipped to £9.4 billion, from £8.2 billion. Exports to the US fell by £329 million—part of a 4.7% drop in exports to non-EU countries, extending a slump that began in October 2011, said the ONS (pdf). The good news was that services posted a surplus of £5.8 billion, in keeping with the uptrend in that critical engine of the UK economy. Here’s what the goods deficit looked like:

Based on today’s and other data, Markit expects that the UK economy grew between 0.1% and 0.2% in the first quarter of 2013, after a 0.3% contraction in Q4 2012. That optimism helped bump the sterling up to a six-week high against the dollar. However, the continuing erosion of demand for UK exports keeps the possibility of a triple-dip recession too close for much comfort.