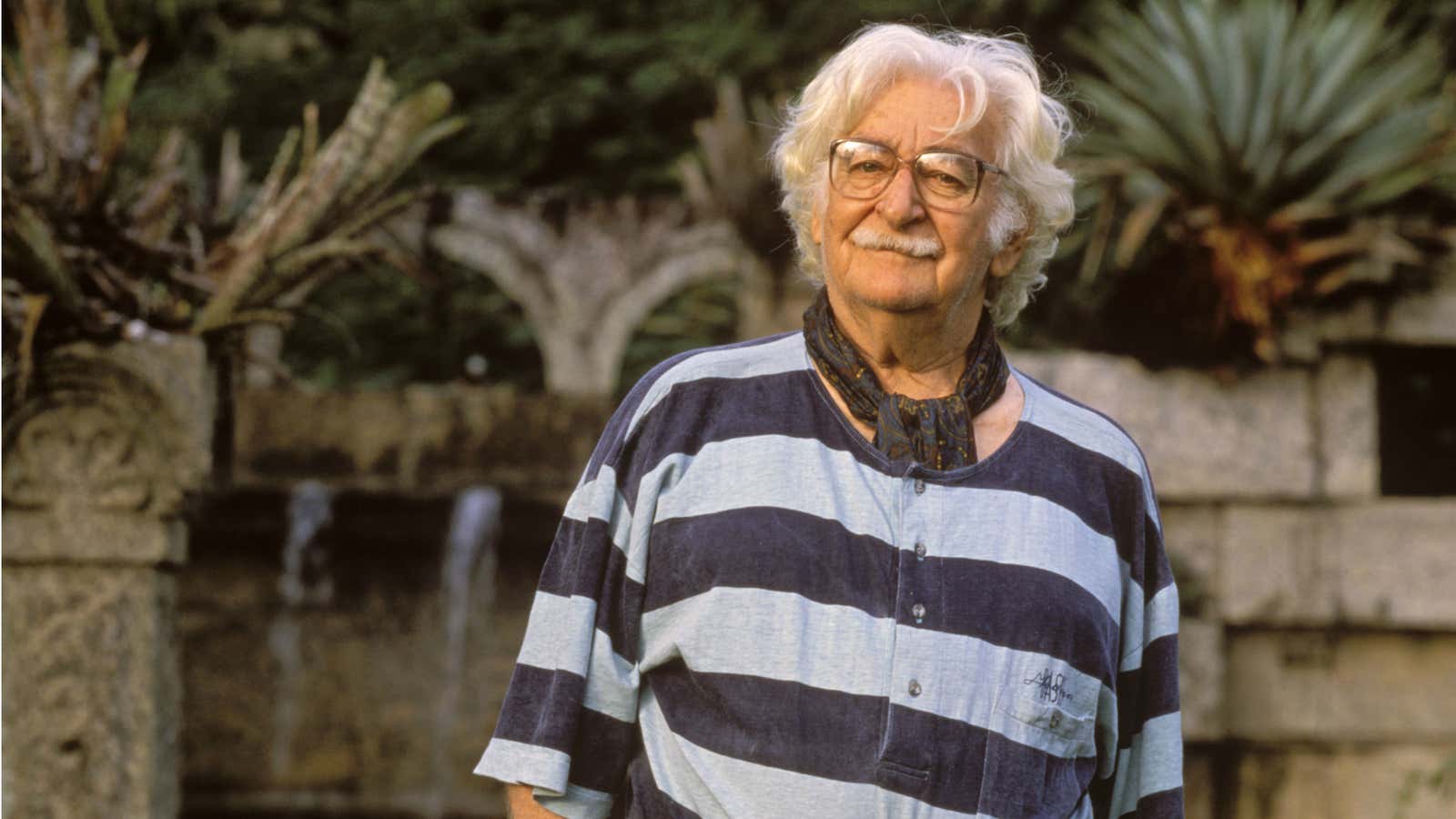

The sense that the Brazilian artist Roberto Burle Marx—perhaps the most influential landscape architect of the 20th century—was generally satisfied with his work, is deeply reassuring. Great artists, Burle Marx shows us, need not be tortured.

“My favorite garden is always the last garden I have done,” he told the LA Times in 1989.

According to Jens Hoffmann and Claudia J. Nahson, the deputy director and curator at New York City’s Jewish Museum, where a retrospective of Burle Marx’s work is currently on view, the unpredictability of nature left Burle Marx at ease with impermanence and imperfection.

“Nature’s instability was for Burle Marx both a stabilizing and a liberating force,” wrote Hoffman and Nahsonn in their introduction to Roberto Burle Marx: Brazilian Modernist.

“It unleashed his creativity. That quality—the sense that life is always in flux—permeates his diverse artistic output. ‘Perfection in a work of art does not exist,’ he said. ‘A work of art is never definitive.’”

The tropical modernist

Burle Marx, who died in 1994, was most famously the man behind the black-and-white tiles that undulate alongside Copacabana Beach in Rio de Janeiro, and a frequent collaborator of Oscar Niemeyer, the architect who defined mid-century modernity in Brazil with his swooping, space-age white buildings. Beyond his seminal work in landscape architecture, Burle Marx was also a painter, sculptor, and designer of textiles and jewelry—not to mention a baritone, cook, mentor, and host. (A guest at a garden party at Burle Marx’s sitio on the outskirts of Rio might have rubbed shoulders with Buckminster Fuller, Alexander Calder, Pablo Neruda, or Susan Sontag.)

But Burle Marx’s primary medium—and the source of the joy that permeates his legacy—was plants.

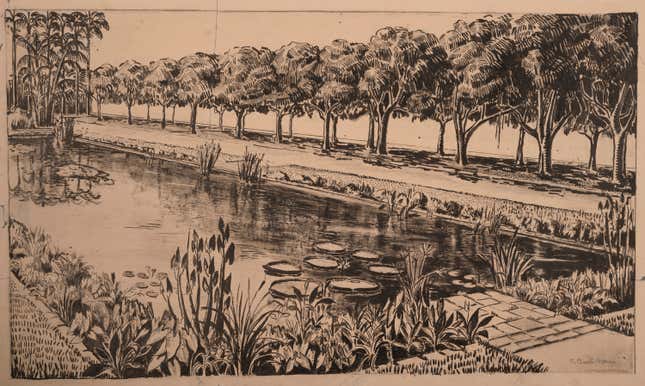

Before the cultural movement of tropicalia took hold—when Brazilian musicians including Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil were exiled for challenging the dictatorship with their electronic embrace of Brazilian samba and bossa nova in the 1960s—Burle Marx similarly defied convention in his celebration of Brazil’s homegrown beauty. Rather than continue the tradition of imitating European gardens with imported flowers and strict symmetry, he planted lush native bromeliads, orchids, and palms in amoeba-shaped formations amidst azulejo tiles.

Burle Marx had discovered many of those native plants himself, on botanical missions into the country’s interior. All told, he designed some 2,000 gardens worldwide and discovered nearly 50 plant species. He credited his productivity and energy to an insatiable natural curiosity:

“Why does nature, with the one hand, create a leaf so broad and tough that a child can float on, and with the other, fashion a flower as tiny as a pinhead containing all the organs for its reproduction?” he asked. ”These mysteries, these forces of nature, are my gods. When I no longer have the curiosity to pursue them, I will surely die.” (He was 79 when he gave the LA Times that interview in Miami, and had gone straight from his flight from Rio to see a rare orchid at a nursery.)

Burle Marx’s sense of perspective extended beyond his work, to his embrace of others. Haruyoshi Ono, who joined Burle Marx as an intern in 1965 and went on to become a partner, and today is the firm’s general director, remembered him as a generous, good-humored mentor and colleague.

“He never discouraged people,” said Haruyoshi. “When people got discouraged, he would say, ‘No, no, we’re going to do it. You’re doing really well!’ And if they said, ‘no, no it’s terrible.’ He’d say, ‘No it’s good. It’s good. Keep going. Continue.’ He always made people feel better.”