Usually, the bond market is a cautious, prudent and a deeply boring place, especially when compared its tempestuous kid cousin, the stock market.

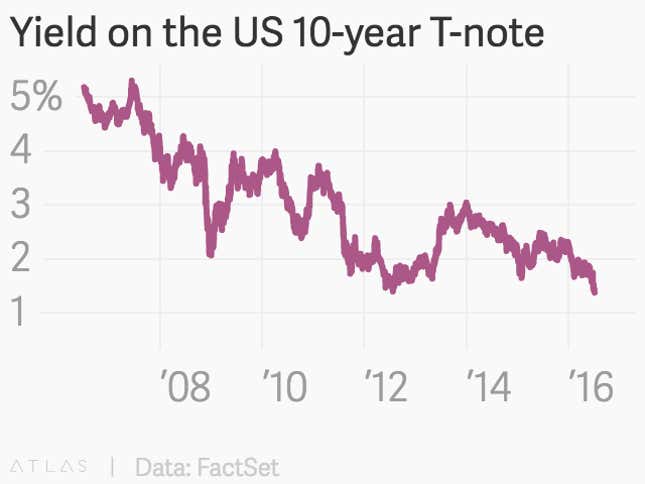

Yields on the key benchmark securities such as the US 10-year Treasury note—that serve as the foundation for rates paid to finance everything from cars and mortgages to skyscrapers and armies—placidly bob around for a few hours before settling a few basis points from where they started. (Basis points are hundredths of a percentage point. So one basis point is 0.01 percentage point.) A big day would see yields move by 10 basis points, or a tenth of a percentage point.

But to really understand what makes the bond market interesting, you have to look at the big picture. A really big picture. You basically need like 200 years worth of data. Luckily, the good people at Global Financial Data have just provided us with just that in the form of monthly US long-term bond yields stretching all the way back to 1786. Using more than two centuries of amalgamated data on long-term high-quality bonds, we can see that interest rates in the US have struck never before seen low levels recently.

This is not a big mystery. Britain’s decision to exit the EU in a referendum late last month has set of a stampede of investors into the safety of assets like US government debt. That surge of buying pushed already-low yields, even lower. (Bond prices and yields move inversely.)

Why were bond yields already low? Well, a bunch of reasons. Piddling global economic growth with disinflation bordering on deflation has kept yields quite low. The bottomless wallets of central bankers—who have been devouring the supply of the safest global bonds in an effort to give economic growth a lift—is another reason.

So is this good or bad news? If you have solid credit and a decent job and you’re looking to get a mortgage and buy a house, or refinance a mortgage, this is incredibly good news. The rate on a conventional 30-year fixed rate mortgage has fallen to near-record lows, setting off something of a refinancing boomlet. If you’re a well-run company looking to borrow and expand, again, this is good news. The same goes for governments who want to borrow and invest in costly infrastructure projects that pay dividends over time.

On the other hand, if you are a bank or financial institution that makes your money on the spread between borrowing short term and lending long term, this is making life more difficult. Likewise if you’re an insurance company trying to buy long-term bonds that pay you enough of a return to match the claims customers will make on you decades in the future, this is a very difficult environment. Lastly, if you’re a member of the global financial aristocracy sitting on vast troves of wealth that you’re used to investing and living off of, this isn’t great.

Like most things in life, where you sit is where you stand.