US legislators are expected to release a draft of a comprehensive immigration-reform bill this week. But right from the start, one of its core provisions—a compromise agreement between labor and business on guest workers—is inherently flawed, according to two labor economists.

The bill also includes provisions that provide a path to citizenship for 11 million undocumented immigrants and improve border security. But the most important economic test is whether it will allow the US to meet its labor needs without forcing workers into the underground economy. The last big immigration reform in 1986 failed that test—and Congress seems ready to repeat its mistakes.

Politicians outsourced negotiations over guest workers to the business lobby, which advocates for large numbers of guest workers and little regulation for the businesses that need them, and trade unions, which want to protect American workers from cut-rate competition. They came up with a deal for a “W Visa” that would allow 20,000 temporary workers per year to come to the US for the first four years, then increase the cap to 75,000 per year and eventually as many as 200,000 per year.

The problem is that the US economy will require many more workers than that, even if high unemployment might mask this reality today.

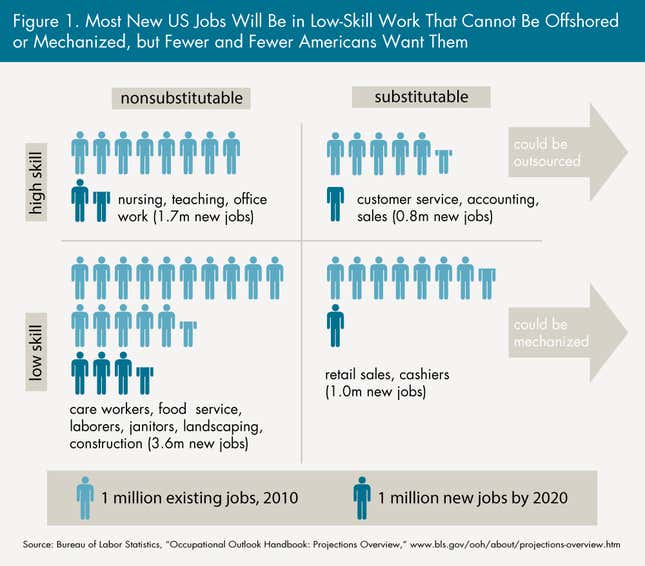

In a forthcoming policy brief, economists Michael Clemens and Lant Pritchett argue that more low-skilled jobs will be created in the US between 2010 and 2020 than there will be workers to fill them. Using a Bureau of Labor Statistics forecast of occupational demand, they broke down jobs by skill level and whether workers could easily be replaced by automation or offshoring:

The bottom line: About 1.7 million new American workers between ages 25-54 will begin looking for jobs in the decade. But there will be demand for 1.6 million high-skilled workers—jobs like nursing, teaching and other professional work done face-to-face—and 3.6 million new low-skilled workers in sectors such as health care, food service, construction and janitorial services.

But wait, won’t people who are currently unemployed pick up the slack? That simply hasn’t happened during the recession, and there’s no reason to think it will change. For example, some skilled workers whose jobs have been outsourced don’t want to take low-skill jobs, and some older unemployed workers have opted for Social Security’s disability pensions.

So, filling all of the new jobs that will be created this decade will be a challenge. Ideally, Clemens says that lawmakers would simply increase the number of green cards issued. But since that’s politically unfeasible, the remaining options are to fill the gap with undocumented immigrants, create a sufficiently large guest worker program, or simply leave the jobs unfilled.

Critics of guest worker programs worry that they will drive down overall wages, but the research by and large suggests that any job displacement or lowering in wages is outweighed by the benefits that the immigrants bring, including this report from Alan Krueger, now the White House’s top economist.

What these critics really miss, Clemens and Pritchett write, is that new low-skilled workers help create new jobs—not only by spending the wages they earn but also by creating demand for more managers, and by protecting industries (particularly tough to harvest crops like apples, cucumbers, lettuce, and melons) that couldn’t exist without cheap labor.

What worries Clemens most of all is that the guest worker compromise doesn’t appear to be looking closely at the United States’ labor needs in the future.

“It was not from a detailed economic analysis of the needs of the country,” he says. “To enshrine in law that the economy in no circumstance will ever need more than 200,000 a year is a strategy for guaranteeing that there will be large numbers of irregular workers in the future again.”