The US government says it doesn’t want to release data about who’s entering the country because it charges for that information. But no one has purchased access to the databases in more than two years, records reveal.

I’m suing for the data in question, which include anonymous immigration records and statistics about international air travelers. The databases would add a lot of information to the debate over US immigration policy at a time when it’s being hotly debated. For instance, how many people from Muslim-majority countries actually enter the country each year? Where are they going? What visas are they using? How old are they? These data would tell us.

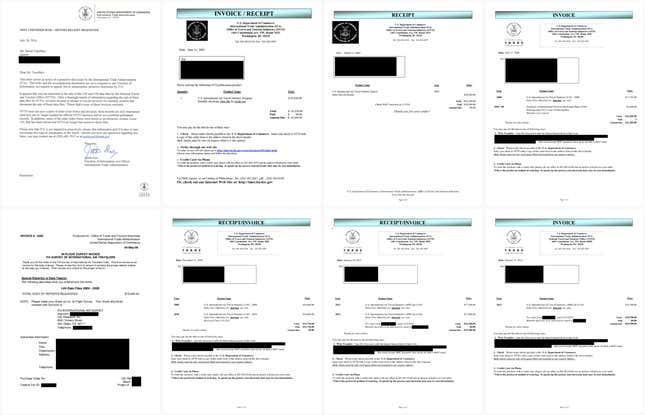

In denying my request for free access, the government offered to sell me five year’s worth of data, instead, for $173,775. That would have been nearly as much money as the government appears to have made selling the data over more than a decade, according to records maintained by the commerce department’s International Trade Administration (ITA).

To get a sense of how much revenue these data generate, I made two public records requests. The ITA ended up giving me seven invoices (pdf) totaling $221,315 that were processed by the ITA since 2003. It’s impossible to tell if those invoices cover all purchases of the data or only some of them. It also indicated that it has no completed order forms (pdf) for the data on file. The ITA declined to comment or provide more information, citing my lawsuit.

Inside the agency, officials expressed concern that giving me the data would disrupt their revenue stream. “If this data is provided for free, we would have to terminate it as we do not receive sufficient funds from ITA to administer each of the programs we manage and provide to the government and industry,” Ron Erdmann, the director of research in the office that manages the data, wrote in an email on May 6, 2016 to his ITA colleagues.

In a later email, he indicated that his office collects $500,000, presumably per year, through the sale of data and reports associated with the data that I seek. The ITA offers for sale not just the full data files that my lawsuit centers around, but also monthly, quarterly, and custom designed reports derived from that base data. Those reports are less expensive than the full data files.

You can read more of the emails, which were part of my records request, here.

The demographic information of the people entering and leaving the US could be of great value to businesses looking to market and attract to tourists. It could let a sightseeing operator know when the highest number of older tourists visit, a hotel know when the most people on temporary business visas are in the country, or a museum know when translators of certain languages are most needed.

The names and address of the billable parties were redacted on the invoices, so it is unclear who is paying and how many different people are using this data. After taking into account similar repeating requests and segregating overlapping requests, the invoices seem to indicate that there have only been four paying customers of this data since 2003. With seven invoices, there could have been at most seven different purchasers represented by these invoices.

Regardless of the exact amount, the revenue generated by these data pales in comparison to the ITA’s total budget, which was $483 million for 2016, with $56.3 million going towards the statistical and analytical offices.

To be sure, Erdmann’s email indicates that the ITA may have been more concerned about protecting the revenue created by the reports derived from this data. “They too could create their own information and sell to the industry,” he wrote to colleagues. The released invoices and the response letter did not contain information about these reports.

In a conspicuously timed twist, the US Department of Commerce, which oversees the ITA, published a notice in the Federal Register on June 20, 2016, that enumerated the fees for the data I seek and included a legal basis for charging for them. It was the first such notice ever published by the ITA.

The timing is conspicuous because, two days later, the government asked for more time to respond to my lawsuit after it said it had discovered that the rationale used to deny my request under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) was used “in error.” The initial rationale for denying my access to the data cited would have benefitted from this fee schedule being on the books at that time. Documents covered by statutes “specifically providing for setting the level of fees” are exempt from release under FOIA.

When the government finally filed its complete response with the court, it used the same justification for withholding the records as used in the Federal Register to justify the fees.