Hate to say it. But I told you so.

We’re nigh on 10 years since the Federal Reserve cut interest rates to near zero, trying to support the economy in the face of an almost total collapse of the US banking system.

And for many of those years, those low interest rates—as well as a range of “unconventional” monetary policies—seemed to have relatively little impact, especially compared to the past, when US consumers had leapt on any decline in interest rates as an excuse to get a new mortgage or refinance an existing one.

There were good reasons why this linkage between lower interest rates and higher economic activity had frayed. The collapse of house prices in the 2008 crash had left many homeowners owing more than their homes were worth. That made refinancing essentially impossible. What’s more, banks were leery of lending more after seeing giant chunks of their loan books go bad in the recession. (The distraction of years of legal woes and hundreds of billions of dollars worth of fines didn’t help either.)

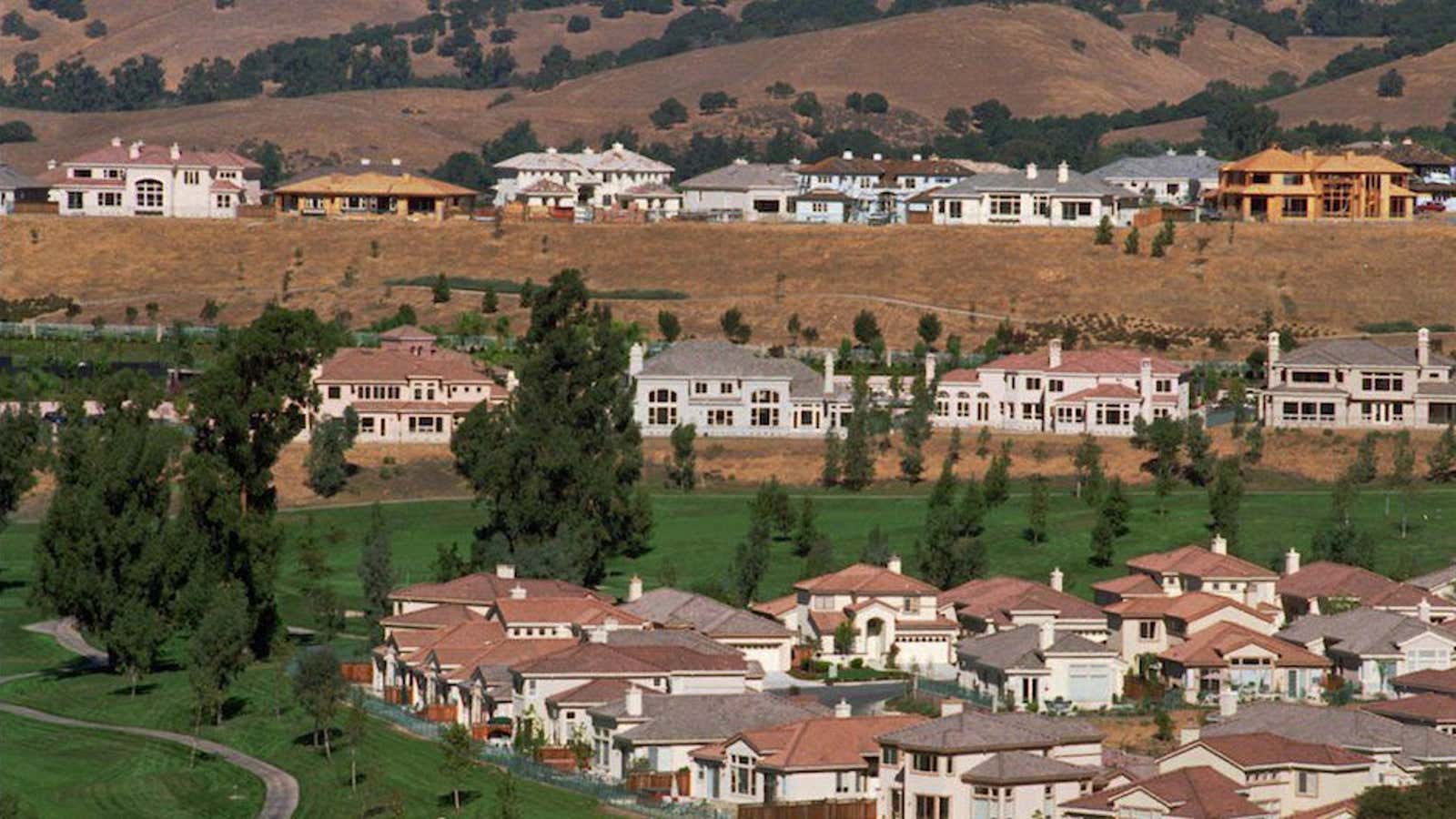

But now, after years of painfully slow growth and healing of household balance sheets, it seems low interest rates are starting to have the desired effect. To wit, just-released statistics show that in June, previously owned homes sold faster than at any time since before the crisis, way back in February 2007.

This is good news. It suggests that important cylinders of the US economic engine continue to fire, despite the slowdown in China and the weakness in Europe (which, in the wake of the UK’s Brexit vote, is likely to continue).

Aside from homes, cars—another interest-rate dependent sector—are going strong too. Last quarter, surging sales of pickup trucks and SUVs pushed GM’s profits up more than 150% year-on-year. It’s hard to think of a more symbolic indicator of American economic confidence than the pickup truck.

The real test of the US economy though, will come as Janet Yellen’s Federal Reserve prepares to bump up the interest rate again later this year. The members of the Fed’s open markets committee are not expected to pull the trigger at their meeting next week, but they could signal their readiness to do so.

A few years back, I’d have been worried that interest-rate increases would undermine the economy. But given the solid indicators, I wouldn’t be surprised if signs of a looming rate increase have the opposite effect—stimulate a bit more activity, as borrowers rush to take advantage of rates near the bottom of the cycle. Yay.