Taking a bus in Latin America can be a disorienting experience. While the light rail systems in places like Mexico City, Buenos Aires, and Rio de Janeiro have system maps that are fairly easy to understand, most cities lack a comprehensive bus map.

Several factors have kept bus maps from taking root in much of Latin America. One reason is that bus lines running through cities tend to be operated by a collection of private companies, so they have less incentive to coordinate. Newspapers and local governments occasionally attempt to create system maps, but none have stuck.

In Managua, Nicaragua, this absence has had a constricting effect on residents’ lives. Most people know the bus lines that take them to school or to work, but don’t stray far from their usual route. “Mobility in Managua is very difficult,” says Felix Delattre, a German programmer and amateur cartographer who moved to Nicaragua 10 years ago to work for an NGO. “People don’t go out at night because they don’t have the information on when the bus is coming and where it’s going.”

Delattre led a group of volunteers who teamed up with university students in Managua to create what they believe to be the first comprehensive bus map in Latin America. The mapping venture is an independent project connected to the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team, a nonprofit group that uses open-source technology and crowdsourcing to create badly needed maps around the world. The team spent almost two years mapping out Managua and Ciudad Sandino and recording its 46 bus routes.

“Only a grassroots effort like that is going to be successful,” says Blake Girardot, president of the Humanitarian OpenStreetMaps Team. “It has to be local people doing it, or you have to talk to a lot of local people.”

First, team members created an up-to-date base map of Managua using satellite imagery on computers. Then pairs of volunteers went out on bus routes with GPS devices or smartphones to make note of all the stops, asking fellow passengers what the stops were called. Only some of the stops have official, government-sanctioned names, and even those are often more commonly known by unofficial monikers.

Managua residents’ reliance on landmark-based directions is a necessity, not a quirk, considering that many streets don’t have names, according to Karl Offen, an associate professor of environmental studies at Oberlin College who co-edited Mapping Latin America: A Cartography Reader.

“Managua has tried to put up street signs on bigger boulevards,” says Offen, who lived in Managua during the 1990s. “But there’s a popular culture that resists these official proclamations.”

Delattre, who also runs the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team’s website, says he was mindful to avoid imposing his northern transit map ideology on the Managua project. “Addresses in Nicaragua aren’t based on street names but on reference points. They perceive their space in a very visual way,” he says. “We had to make the style in the way people perceive it and make it easier for people to read it, especially when you take in account there is still some illiteracy, and people are not used to reading maps.”

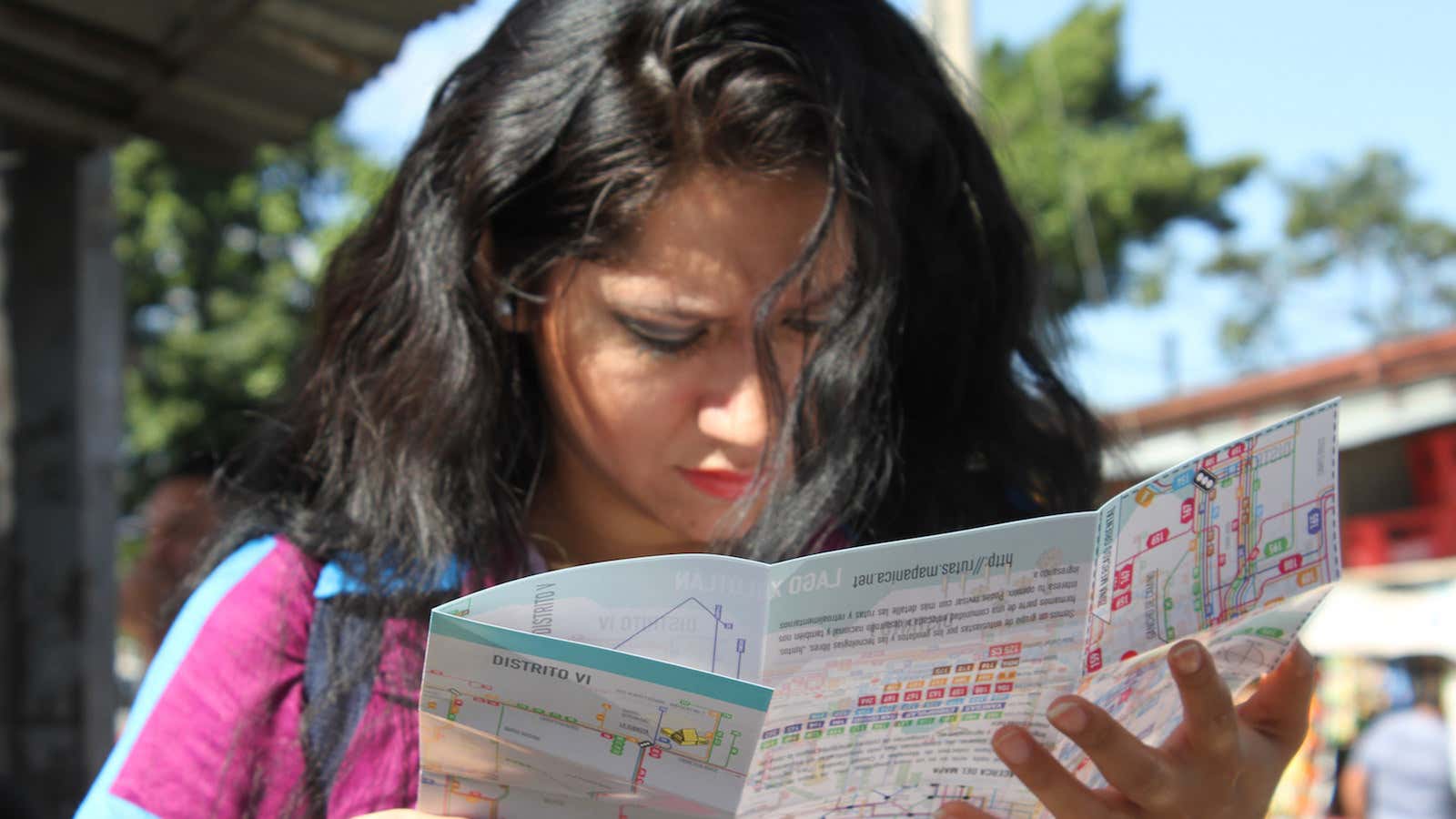

The final transit map was designed by a Managua firm, Ninfus Design Studio, and includes images of well-known landmarks, like statues and water towers. Once finished, a crowdfunding campaign paid for the printing of 40,000 paper copies of the Managua map which were then distributed by volunteers on buses and at central stations throughout the city. It’s also available for free online.

Mark Ovenden is the author of Transit Maps of the World, which critiques designs of light rail and subway systems’ network schematics. I asked him what he thought of the Managua map. “That is a bloody great job they’ve done there,” he says. “I even like the inclusion of these oversize landmarks.”

Delattre reports the maps been very well received so far, especially among bus drivers. One bus driver told him that on his first day of work he’d been given a bus and set out on the road without any instructions on where to go. He had to rely on passengers’ directions and made lots of wrong turns. Now, the guesswork has been taken out of his job.

OpenStreetMap volunteers and Managua students hope the maps will open up new opportunities for the city’s residents. They’re already hosting mapping parties where people could learn about cartography, wayfinding and how to use and edit OpenStreetMaps.

“If you have a map and you’re able to read it then you can actually do more, try some things in your life or help you get a job,” Delattre says.

The project isn’t over yet, however. While the map is complete, the team still only has a vague idea of when buses start running and when service ends. They hope to raise an additional $1,000 in order to collect information on bus schedules and build a free mobile app that will help residents figure out the most efficient routes to their destinations. Delattre is excited to see local contributions continue: “It’s about doing something with technology that everybody can do, not just consuming technology.”