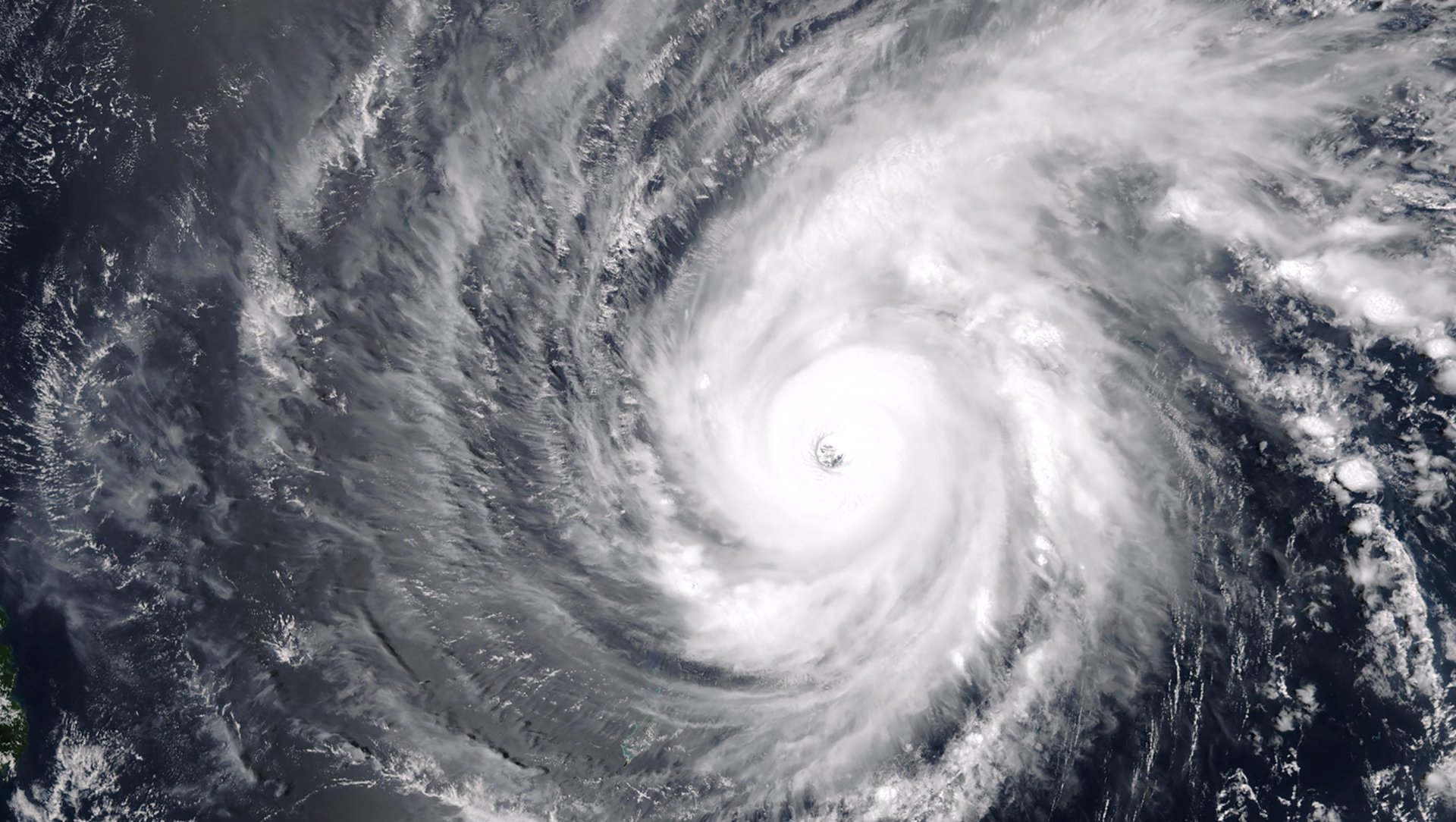

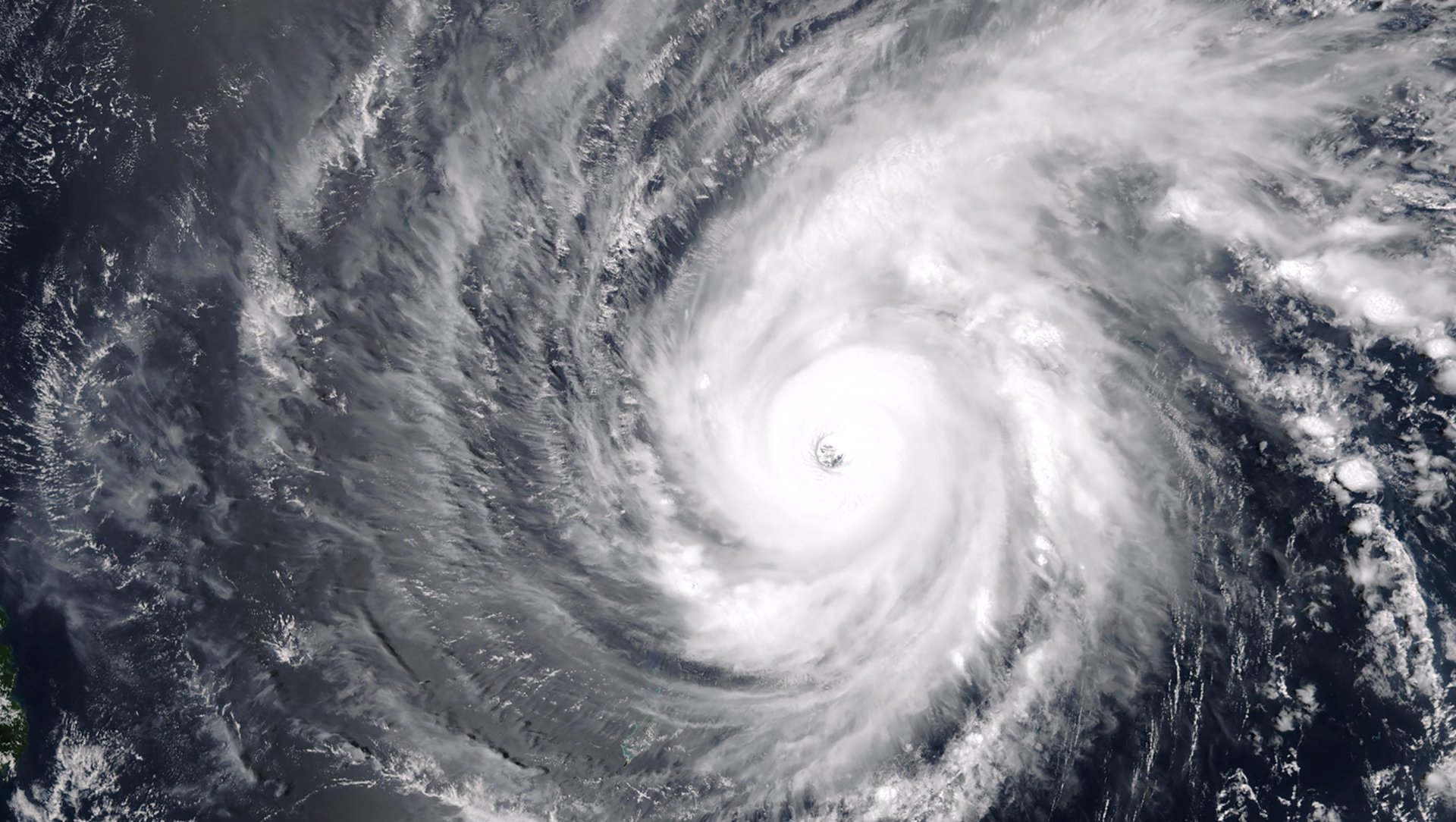

It’s typhoon season in the South China Sea—and China’s fake islands could be washed away

Typhoon Nida is barreling through the South China Sea, after dumping over 300 millimeters of rain on the Philippines over the weekend. As Hong Kong braces for landfall sometime tonight (Aug. 1), some controversial, much-less-populated landmasses may already be feeling the brunt of the storm.

Typhoon Nida is barreling through the South China Sea, after dumping over 300 millimeters of rain on the Philippines over the weekend. As Hong Kong braces for landfall sometime tonight (Aug. 1), some controversial, much-less-populated landmasses may already be feeling the brunt of the storm.

That’s because in the past few years China has rapidly built artificial islands in the South China Sea, cramming them with buildings, runways, and lighthouses—even a farm—in an effort to bolster its territorial claim to most of the sea. Those projects came under legal attack in a landmark ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague on July 12, which took up the case under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Nature, though, may prove to be an even more powerful threat than international law.

While China promptly vowed to ignore the ruling and continue building islands as it sees fit, it could find itself in a losing battle against waves, typhoons, and rising sea levels as it tries to bolster structures built atop fragile, damaged reefs.

Months after constructing an island atop Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratly archipelago, for instance, China had to repair a corner of it that had, satellite imagery showed, collapsed into the sea.

Correctly sloping walls can be a challenge with such structures. But a more fundamental problem is that reefs are generally hit by a great deal of wave energy—and the same goes for anything built atop them. A 2014 study (pdf) published in the journal Nature Communications examined the beneficial aspects of coral reefs in reducing natural hazards for coastal populations. It found that reefs reduce wave energy by 97% on average. Reef crests, or the seaward edge of a reef (often the shallowest part), dissipate about 86% of the energy. That’s a lot of wave energy pounding into a structure.

What’s more, if sea levels rise, the damaged reefs might be unable to make natural adjustments, in turn weakening whatever is built atop of them. The walls of a base ”can be undercut if the crests weaken due to having concrete structures sitting on and killing the microbial ecosystems which keep them repairing themselves and growing upwards with sea level,” noted marine biologist John McManus, a professor at the University of Miami in Florida who’s proposed turning the Spratlys into a international marine reserve.

Typhoons and super typhoons occasionally rip through the South China Sea, especially during the summer months. A structure like Fiery Cross Reef is precarious enough in normal conditions. A super typhoon (pdf) carrying winds of 185 km per hour (115 mph) or higher and waves of possibly six meters (19 feet) could wipe it out, or cause severe damage at the very least.

Many of the structures on China’s fake islands are facing their very first typhoon season. Nida alone is expected to pick up strength as it crosses the South China Sea, and could be a Category 2 hurricane before it makes landfall on mainland China.

The Permanent Court of Arbitration found China in violation (pdf, p. 416) of UNCLOS articles concerning the protection of the marine environment, noting it had caused “devastating and long-lasting damage” to seven reefs in the Spratlys while island-building: Cuarteron Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, Gaven Reef (North), Johnson Reef, Hughes Reef, Subi Reef, and Mischief Reef.

While Beijing seems determined to weather the legal storm caused by its artificial islands, it remains to be seen whether its precarious structures can withstand natural storms.