In this series, Perfect Company, we are examining pockets of excellence in the corporate world. No single company is perfect, but together they show what the corporate ideal could look like.

The platonic ideal

“Good marketers see consumers as complete human beings with all the dimensions real people have.” – Jonah Sachs, Winning the Story Wars

The practice

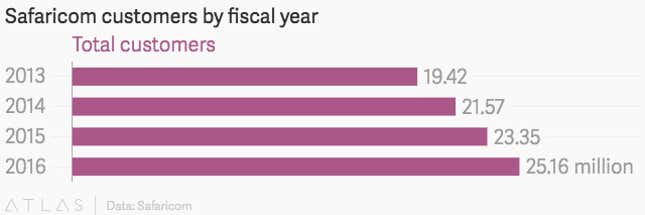

For the last 16 years Safaricom, Kenya’s largest publicly traded company and East Africa’s largest telecom, has focused on signing up more mobile subscribers. With 87% of Kenya’s population already subscribed to mobile phone plans, Safaricom, partly owned by Britain’s Vodafone—along with its newer rivals such as India’s Bharti Airtel or Orange Kenya, partly owned by France’s Orange SA—are now chasing a smaller slice of the pie.

So far, Safaricom is grabbing the most of that slice, with about 25 million subscribers and a market share of almost 70%. Its mobile-money platform, M-pesa, is the world’s largest, with more than $50 billion in transactions a year; it’s used by more than half of Kenyan adults.

But Safaricom, one of the earliest telecoms in the region, worries it won’t always be on top. Competition is becoming more intense and customers have more choices. Safaricom, while dominant, lacked customer loyalty, its executives realized more than a year ago.

“We had a bit of a challenge where we had people using Safaricom by default just because it’s big. It’s there,” says Charles Wanjohi, head of customer segmentation, who was hired from rival Airtel to start the department last year. “The challenge is how to make all these 25 million people love you.”

To achieve that, the company has been going through a transformation over the past year. It’s been focused on changing itself into a “consumer-led” business. This means using data and research to organize marketing, distribution, customer service, and product offerings—basically all decisions—around niche markets.

Potential and existing Safaricom customers are classified and analyzed not just by their age and income, but instead according to a series of ”psychographics,” or attitudes and aspirations.

Instead of looking to other telecom companies, Safaricom emulates consumer goods companies like Procter and Gamble that have long used principles of market segmentation.

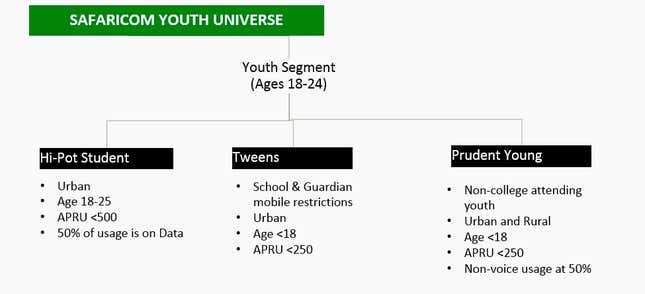

Safaricom’s consumer segments are based on four broad categories, divided into 16 sub-segments, which include: “young flashers,” entry-level professionals eager to show off their newfound wealth; “savvy loyalists,” self-employed entrepreneurs age 4o and up who like to keep their money under wraps; “mature trendies,” young families; or the “prudent young,” youth who work and have responsibilities.

Some of these segments are broken into smaller groups, a process that Wanjohi says is “ever evolving.” They are based in their average spending, or “ARPU” average revenue per user, education level, age, and less tangible factors like their “attitude toward life.”

The company has begun more heavily targeting Kenya’s various regions over the past year. These range from pastoralist communities to the coast where most of the country’s Muslims live, or tribes that prefer their own language over Kiswahili or English, Kenya’s two national languages, notes Musau.

A lot of Wanjohi’s efforts have been getting the staff to think in the mindset of its customers. Charts of the “Safaricom universe” are taped to the cubicles outside Wanjohi’s office. Staff parties are held where different departments dress up as a consumer segment.

All marketing campaigns are customized to target these specific groups. The approach applies to customer service, too. Staff at the its customer care centers are subdivided according to the customer segments they serve.

“One fundamental thing is that we have become cognizant of the customer in all our decision making, across the whole company, “Wanjohi said.

Immersive research has been important as well. Wanjohi recently assigned his staff an exercise in understanding one of their lower income groups, the “mass segment” customer. Teams were sent out to buy 4,000 shillings ($40) worth of goods they thought that consumer would buy. The same amount of money was given to real customers that his team then followed on their shopping trip.

The results were surprising. Instead of spending the bulk of their money on basic food items and Kenyan staples like maize and flour, these shoppers also bought more costly basics like rice, cooking oil, laundry detergent, and toothpaste, in small amounts.

“The exercise taught us that to understand each segment, we had to experience what it’s like for consumers within that segment,” Wanjohi said.

The segment the company is most focused on now is Kenya’s 11 million working-age young people. They don’t have a lot of buying power now, but as many as 1 million Kenyans between the ages of 15 and 25 are signing up for mobile phone services a year, according to Musau. In a few years they will start earning an income. Wanjohi says the company expects to see 25% of its growth to come from the youth market over the next few years.

To appeal to this group of ”high pot students,” or high potential university students, “tweens,” youth as young as 10 years old, or “prudent young,” Safaricom launched a sub-brand called BLAZE in June.

The brand—which includes cell phones, SIM cards, and customizable phone plans to mentorship programs, youth summits, and a television show—is built around the idea of being your own boss, or BYOB. Mentors and BLAZE brand ambassadors are self-employed young Kenyans who have established untraditional careers in things like Thai boxing, dancing, or music.

“When we landed on this segment of young people, we found this tension that people want success but the opportunities are very limited, ” Wanjohi said. As many as half a million new Kenyan graduates are competing for just 30,000 jobs a year, one reason why the country has the highest youth unemployment rates, almost 20%, in East Africa.

The takeaways

In the year since Safaricom began focusing on segmentation, its net profit rose 19.5% for the year ending March 2016 to 38.1 billion Kenyan shillings ($375 million). Its increase in customers this past year, almost 8%, was the highest in five years, according to Musau.

“[This approach] is already translating into success when you look into our engagement and brand scores with consumers,” Wanjohi said, but declined to share those scores.

Wanjohi admits that there has been a learning curve. His department has had to overturn assumptions about young Kenyans. ”There’s a perception that the youth are all about the party lifestyle, but we found they are very driven and very entrepreneurial from a very young age.”

Another issue has been translating segmentation into usable measures of performance. “You can define the consumer very well, you can see the consumer in your head, but if you can’t match the consumer with the internal reporting system then you have a big challenge,” Wanjohi says.

“The challenge is how do you make sure you marry the customer description with how they are described in the reporting system? So, when you are doing the reporting … you can say, ‘This is the customer group that is bringing the growth.'”

The biggest risk in this approach may be offending customers with simplistic or off-base characterizations. “Very few firms ever recover from this,” says Mary Onguko, relationship manager at Imarasat, a broadband provider to African businesses who published a 2014 paper on segmentation on Kenya’s telecom industry.

Airtel, one of Safaricom’s rivals, once focused almost entirely on mobile phone users of the highest-income group, ignoring the larger but poorer wanjiku or “common man.” Airtel has since tried to reverse course, Onguko says, but now lags Safaricom, which took that opportunity to establish itself as the everyman’s service provider.

It’s partly for this reason that Wanjohi is hesitant to reveal all the names the company has used to describe its segments. Some of them have verged on the offensive, leading Wanjohi to make some recent “refinements” to the category names. To him, this is as important for implementation as it is for appearance.

“How you name your consumers affects your perception of them,” he says. “You need to have a picture of the customer in your mind. You always want to have a positive view of the customer group.”