The system for catching dangerous pathogens in America’s food supply is finally working

No one saw it coming. A single ice cream sandwich, temporarily rattling a nation’s faith in frozen dessert.

No one saw it coming. A single ice cream sandwich, temporarily rattling a nation’s faith in frozen dessert.

Truth be told, it might have shocked Megan Davis the most.

“You hear about recalls everyday, but you never really think you would be the one who would find the sample,” says Davis, who, at the time, was with the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control’s food safety lab.

It was her three-person team that in February 2015 first discovered the microscopic Listeria pathogen lurking in a couple of ice cream bars pulled from a Blue Bell Creameries distribution center in Lexington, South Carolina. By the end of April, Blue Bell sent out a public request that all its ice cream products—more than 8 million gallons of the stuff—be removed from every home and store freezer.

The company cut 37% of its staff, furloughed many more and imposed wage reductions. It was the fallout from the first product recall in Blue Bell’s 108-year history, which almost drove the beloved Texas-based brand into ruin. The signs of a Listeria infection can be tough to distinguish from other infections—flu-like symptoms, including muscle aches and nausea—but can also be deadly when it strikes people with weakened immune systems. The Blue Bell outbreak wound up sickening at least 10 people across four states and led to four deaths.

“It was overwhelming,” says Davis. “I mean, really it was hard to believe the impact of finding two positive samples.”

It was a horrifying scenario to watch unfold. Weeks of damning headlines, illnesses across several states, and the entire dismantling of a trusted brand. And it was just one of hundreds of food safety outbreaks that same year.

The reality, though, is that it was a sign of something good. The increase in alerts about food illness outbreaks and product recalls is a signal that the system for testing food for dangerous pathogens is working, and making strides toward improvement.

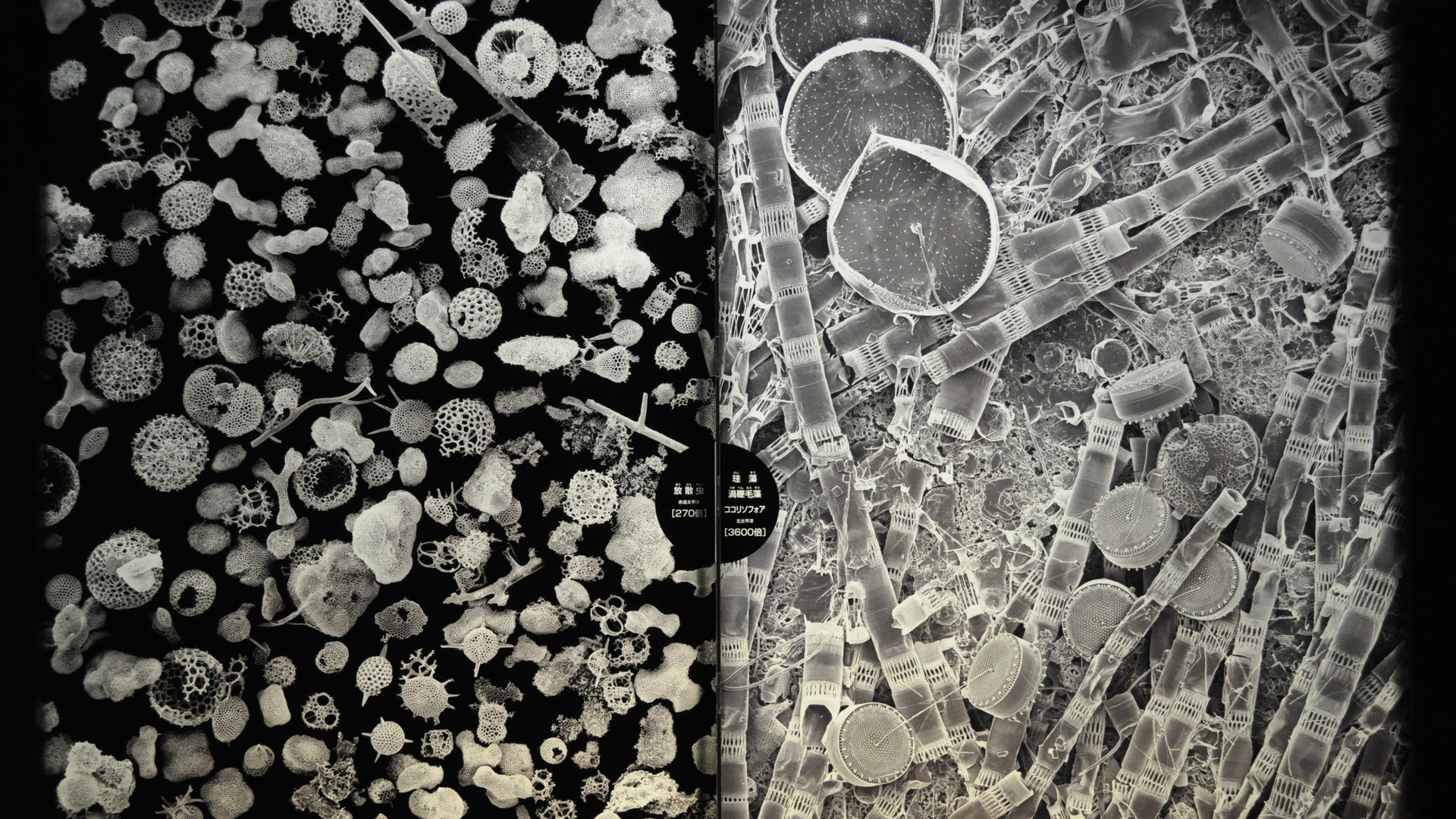

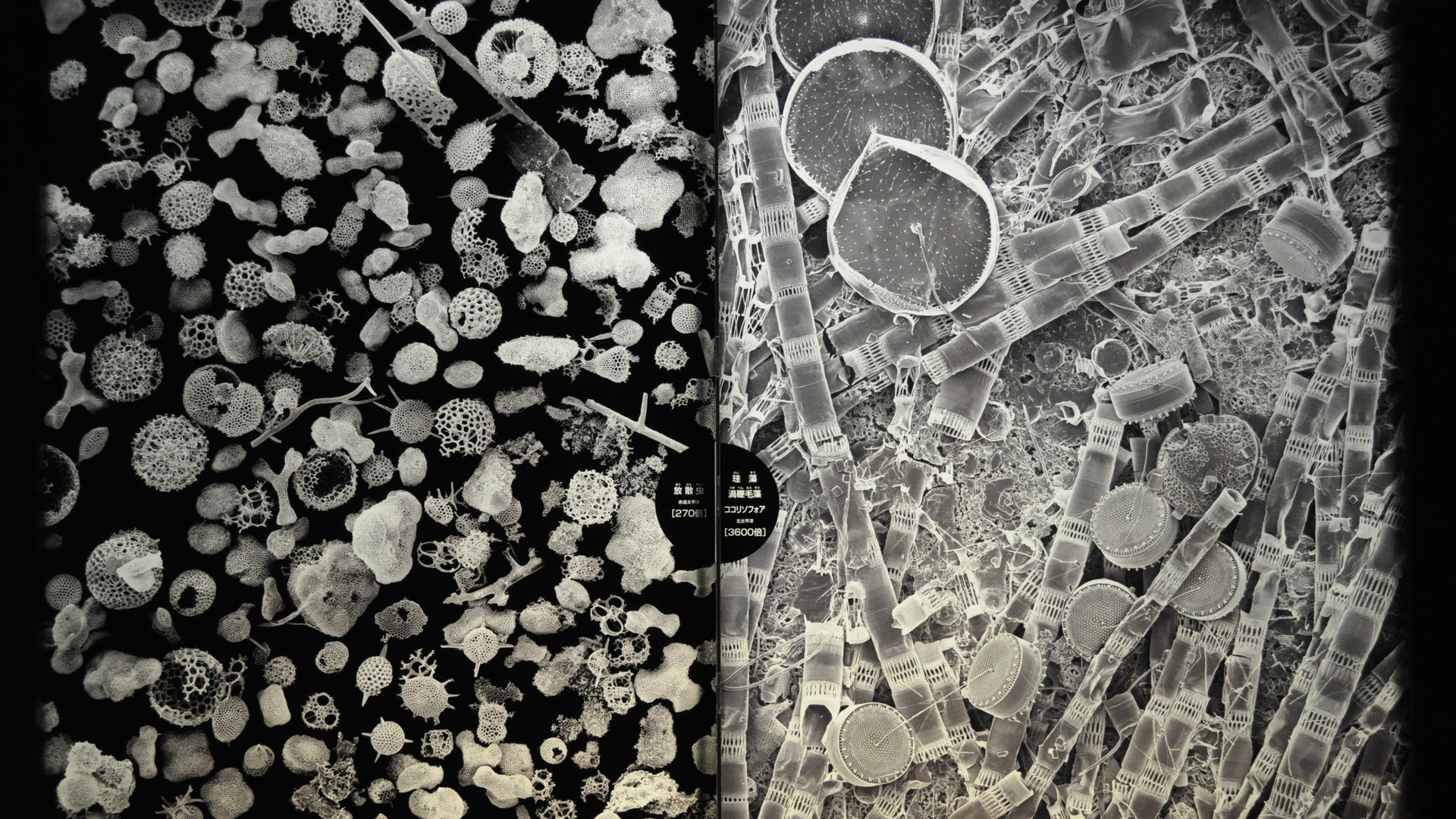

Invisible threats

Foodborne pathogens are tricky to pin down. They’re true shape shifters—creepy little threats that can find their way to a person through almost any food that hasn’t been fully cooked or processed. They could travel as easily via cheeseburger as in a box of supermarket cake mix.

They also seem to be a never-ending threat; there are headlines about tainted food on a near-daily basis. Then there are the big ones. For example, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on Aug. 5 announced Salmonella hiding in green sprouts was behind a nine-state health outbreak that sickened at least 30 people. A month earlier, a massive 21-state E. coli outbreak linked to General Mills led the company to recall more than 45 million pounds of some of its most popular flours and Betty Crocker-branded cake mixes. So far, at least 46 people have been infected and 13 hospitalized (at least one person is now suffering from kidney failure). Both of these outbreaks have yet to be contained.

Those are just a couple of cases that surfaced this summer, two blips on a constantly-updated government list of recalls. As a snapshot of food safety in the US, they are reminders of how unexpected and damaging foodborne illnesses can be. More broadly, they raise the specter of how the public is put at risk when food companies are allowed to self-regulate.

There have been dozens of examples of companies cutting corners and ignoring warning signs over the past few decades, including:

- In 1993, burgers served at 73 locations of the fast-food chain Jack in the Box were linked to an E. coli epidemic that infected 732 people, mostly children under 10 years old. Four children wound up dying and 178 people were left with permanent injuries, including brain and kidney damage. That could have been avoided if Jack in the Box hadn’t ignored a warning by the Washington state public health department that told the company it should increase the temperatures at which it cooked its “Monster” burgers from 140 to 155 degrees Fahrenheit.

- In 2007, agribusiness giant ConAgra failed to properly maintain one of its peanut butter plants in Sylvester, Georgia. A malfunctioning sprinkler system and a leaky roof allowed rainwater and bird feces into the plant, leading to salmonella-tainted Peter Pan peanut butter. More than 600 people fell ill and the company was fined $11.2 million.

- In 2009, executives at the Peanut Corporation of America actually knew their peanut butter was tainted with salmonella and still let it get shipped out to consumers. Federal investigators later found one of the company’s facilities had a leaky roof and was infested with roaches and rodents.

- In 2015, too little surveillance over its supply chain led to a norovirus outbreak at Chipotle, sickening more than 300 people across 14 states and 22 hospitalizations. The company has spent all of 2016 revamping its food safety program in an attempt to regain consumer favor, even as foot traffic in its restaurant have declined by 20%, the company said in July.

Uncle Sam gets involved

That could be changing, as the government implements sweeping legislation signed into law by president Barack Obama in 2011. The Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) will, among other things, hold companies more accountable for testing and will force them to react, by law, if something potentially dangerous is detected in their factories.

“If an ice cream company found Listeria in its facility pre-FSMA, it wasn’t required to do anything,” says Sandy Eskin, director of the Pew Charitable Trusts’ food safety campaign. “Now, starting in mid-September, they’re going to be responsible…for taking steps to prevent problems and the government is going to hold them accountable.”

The FSMA gave the government, for the first time, more oversight and access to company records in sectors of the food system beyond just meat and poultry, including massive manufacturers such as Nestlé, General Mills, Unilever and Pepsico. The rules of FSMA are still being implemented, but once up-and-running they will represent a sea change in how the government protects the public, says Eskin.

The law includes provisions for better testing throughout the produce sector, at US ports for imported foods, mandatory food recalls, and minimum factory inspection requirements. Implementing all of that will be expensive, though. The Obama administration, in its FSMA budget requests sent to Congress each year, has consistently asked to add more money to fund the law despite a difficult political climate in DC. Still, the White House’s requests have called for less discretionary funding than the FDA has said it will need to implement the law.

Not surprisingly, when the government gets involved results follow. After the Jack in the Box burger scandal, the US government decided to classify E. coli as an “adulterant,” which gave it the legal blessing to unilaterally decide to sample and test food products for the bacteria, as well as the power to recall possibly-contaminated products without waiting on reports of human illnesses. Since then, the number of E. coli cases in the US did drop, according to CDC data.

“You look back over time and, from 1993-2003, about 90% of my firm’s revenue was from E. coli cases connected to hamburger,” says Bill Marler, the most prominent food safety attorney in the US. “I was highly critical of the beef people for decades, but I am very positive of them now.”

Salmonella, on the other hand, is still not classified as an adulterant, despite years of health advocacy groups pushing for the change. Unlike E. coli, the number of illnesses attributed to salmonella have remained relatively consistent.

When a company loses control of a food safety problem, it chips away at the public’s trust of that brand—but also in the larger food system.

But there’s public perception and then there is the truth. Consumers tend to believe that the US food system is a perilous landscape to navigate—more than three-quarters of Americans say they are concerned about food safety, according to a June 2016 Harris Poll.

“I think that consumers are seeing these massive amounts of recalls all over the TV and people are starting to go, ‘Well shit, the wheels of the bus have come off,’ ” says Marler.

The reality, though, is that’s a good thing: the increase of alerts about food illness outbreaks and product recalls is a sign the system for testing food for pathogens is finally starting to work.

The data back it up: over the last two decades show illnesses during outbreaks have decreased, from 27,156 cases in 1998 to 13,287 in 2014.

It’s all about culture

Perhaps most importantly, the rise in testing and recalls is forcing the food industry to change its food safety culture.

For example, in Nestlé’s newly-revamped food safety laboratory in Dublin, Ohio, the company has gone to great pains to ensure employees feel encouraged to report food safety problems the moment they arise. That means setting up a chain-of-command that facilitates such reports. Lab director Aaron Ayres reports directly to management at the company’s headquarters in Vevey, Switzerland—not to an executive in the US, who would have a stake in performance and thus an interest in lab results.

Nestlé has also chosen to develop, fund, and build its own food safety laboratories—spending $31 million in the process—instead of outsourcing the work to third-party labs. As the company explained it, they chose to make this investment because they believe the work that happens in those third-party labs can often be reduced by a company to a line item on a budget, a cost to manage, something to check off the checklist. Marler agreed Nestlé’s reasoning made sense.

The company has also established rigorous—even onerous—policies for suppliers, including testing the soil in which its pumpkin seeds are grown and the wheat used to produce to flour that goes into many of its products. The Nestlé facility is now the largest of its kind, and tests the quality of every product line the company distributes across the Western Hemisphere.

But what’s happening at Nestlé is the result of 150 years of trial and error, and having many billions of dollars to achieve its goals. What about newer, smaller chains who seek to beef up their food safety efforts, such as Chipotle?

The 23-year-old burrito chain is in the process of rebuilding its food safety culture in the aftermath of the 2015 norovirus disaster. The company has hired four industry leaders known for their work in food safety, tinkered with its supply chain processes, launched a traceability program to better track its foods, and now incentivizes employees to speak up when they notice something wrong.

“A full 50% of managers bonuses are now tied to performance on food safety measures,” says Chipotle spokesman Chris Arnold. “[It] underscores the importance we are placing on food safety and will help ensure that our teams remain really focused on food safety.”

On the other hand, some companies still choose not to share details about in-house approaches to food safety. General Mills is currently mired in its contaminated flour scandal, yet when asked how it plans to avoid a repeat food safety scare, the company minimized the recall, which has so far left dozens hospitalized.

“Even with the seemingly large amount of flour recalled so far, it still represents a very small percentage of the flour we produce,” a spokesperson said in a statement, adding, “General Mills has suggested to the FDA that they bring together experts to work with FDA and CDC to conduct research and identify long-term solutions to determine if testing protocols need to change.”

There’s still a long way to go. The CDC has said many illnesses still go unreported, and estimates nearly 48 million Americans overall are sickened by foodborne illnesses each year, leading to 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths. But the way the country addresses food safety has undoubtedly improved over time, enough that it gave Marler momentary pause.

“I may never quite be put out of business before I just decide to retire, but the volume of work that I have in my office is less than it was a decade ago,” he says.