Andy Warhol once said that in the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes. My 15 minutes arrived in the summer of 2014, when I found out that I was going to be a contestant on ABC’s Who Wants to Be A Millionaire.

I got the call that I’d been picked for the show while I was at work. After quietly freaking out in my office for a good half hour, the panic started to set in. What if I embarrass myself on national television? What if my mind goes blank onstage? What if I completely waste my one-time shot at fame and fortune?

I knew that a lot of what would happen on the game show would be beyond my control. But I am the kind of person who arrives an hour early for a concert and spends hours on Yelp before picking a pet groomer. I googled every single professor in the English department before registering for classes in college. I don’t like leaving things to chance. So I decided to do everything humanly possible to make the most of the opportunity. In the end, I walked away with a cool $68,000—and several important lessons about how to survive in high-stakes situations with a lot of unknowns.

1. Work with what you know

One of the tricky things about Who Wants to Be a Millionaire is that the questions aren’t necessarily academic. On the practice quiz in the audition, we were asked questions like “Who invented Flaming Hot Cheetos?” “What is the hardest type of pencil lead?” and “What is the holographic symbol on a Visa card?” You don’t have to be a brainiac to answer these kinds of questions correctly. But they also make it really hard to feel well-prepared.

Since I had no idea what kind of questions I would face on Millionaire, I decided to make the most out of the concrete information I did have: a copy of the game show’s official rulebook and daily Millionaire reruns.

Some of you may remember the “Millionaire classic” rules from back when Regis Philbin hosted the show. The rules have changed a bit over the years. A quick rundown of gameplay during my season:

- There are two rounds of questions. The first round has 10 questions that are randomized by both difficulty level and dollar amount, and worth a total of $68,600. The second round consists of four questions that escalate in both difficulty and prize money. If you get the first question right, you win $100,000. From there, the questions are worth $250,000, $500000, and finally, $1,000,000.

- If you get anything wrong in the first round, you win $1,000. If you choose to walk away, you get half your banked amount.

- If you get anything wrong in the second round, you win $25,000. If you choose to walk away, you get your entire banked amount.

- There are three lifelines. The new lifelines are “Jump the Question,” which lets you skip the question, and “Plus One Guest,” where you bring someone up on stage to help you answer a question. “Ask the Audience,” in which contestants poll the audience for answers, is the third.

After watching the show, I began to realize that these rules weren’t just rules. They were a data set that I could try to use to my advantage.

Next, I went over the official rules to my dad, an admitted math wonk. He did a quick analysis to come up with some general guidelines for playing the game.

First, we examined each question in terms of “expected value.” For example, say you have a bank of $500,000 so far, and you think you have a 50/50 chance of getting the question right. On a psychological level, you might want to go with the $500,000 sure thing instead of shooting for the higher “expected value” of $1,000,000. But pure math would suggest that you should try to answer.

Looking only at the mathematical odds, my dad and I came up with a few principles for playing the game:

General principles

- If you don’t know an answer for sure, try to eliminate some of the possible answers.

- If you’ve got less than $10,000 in the bank, you’re better off answering the questions even if you’re not sure.

Lifelines

- Lifelines get more valuable as your bank increases

- You have a better probability of reaching the second round if you use both of your lifelines in the first round. But there is a better expected outcome if you save the lifelines until round two.

- The Ask the Audience lifeline is only worthwhile in a category that the general public knows about (e.g., not the hardest difficulty rating)

- The greater your total, the more willing you should be to use exercise your right to skip a question

- Althought it might seem counterintuitive, the ideal time to use the Jump lifeline is late in the first round, especially with low-value questions left.

2. Learn from examples

These principles gave me a basic understanding of how to play the game well. But I still had a ways to go.

In school, if you want to ace a test, you hit the books. But given how random the Millionaire questions are, I couldn’t just study up on select categories like African rivers and American literature. I needed to figure out a different way to practice.

So, armed with a DVR and an Excel spreadsheet, I spent the next two months recording every single Millionaire episode that aired. I watched the new episodes, the 2am reruns, the web clips—anything I could get my hands on. I answered every question that a contestant was asked on air, and logged my responses on my spreadsheet under four categories: “Knew it for sure,” “Instinct was right,” “Instinct was wrong,” or “No idea.” I also kept track of when the audience answers were right and wrong every time that lifeline was used.

After watching over 40 episodes of the show, I had a good idea about my abilities and probable success rate. Here were my stats:

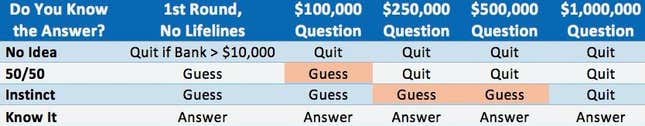

I sent my stats to my father, who then had a love affair with an Excel spreadsheet to produce the definitive guide for how to play Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. Which leads me to the third thing I learned:

3. Make a game plan

My dad-genius ran a bunch of complicated statistical regressions to calculate the estimated value of each round, the probability of my getting the answers right, and how much money I stood to gain by quitting or guessing. He also took into account the fact that the $500,000 and $1,000,000 prizes are distributed in an annuity: you get a $250,000 lump sum, and then subsequent payments over 10 or 20 years, respectively. So a million dollars earned in 2016 would not be worth the same dollar value if it were paid over a 20-year period.

Of course, it’s pretty hard to keep strict formulas and mathematical rules in mind when you’re answering questions in front of a live studio audience. So my dad boiled everything down to a simple chart. The orange cells refer to places where the mathematical odds were slight, but still in the favor of guessing:

The big game

Now I knew when I should answer and I knew when I should quit. All I had to do was play the damn game.

So how did I fare? At the end of the day, I made it through the first round but had to use all my lifelines. I used the “Ask the Audience” lifeline on a question about Led Zeppelin’s hairstyles (not my musical genre, nor my decade). For the “Plus One Guest” lifeline, I brought up my boyfriend to help me answer a geography question (my worst subject in school). I used “Jump the Question” on an American history question, but realized later that I actually knew the answer—I had been confused by the phrasing. Luckily the question was only worth $500.

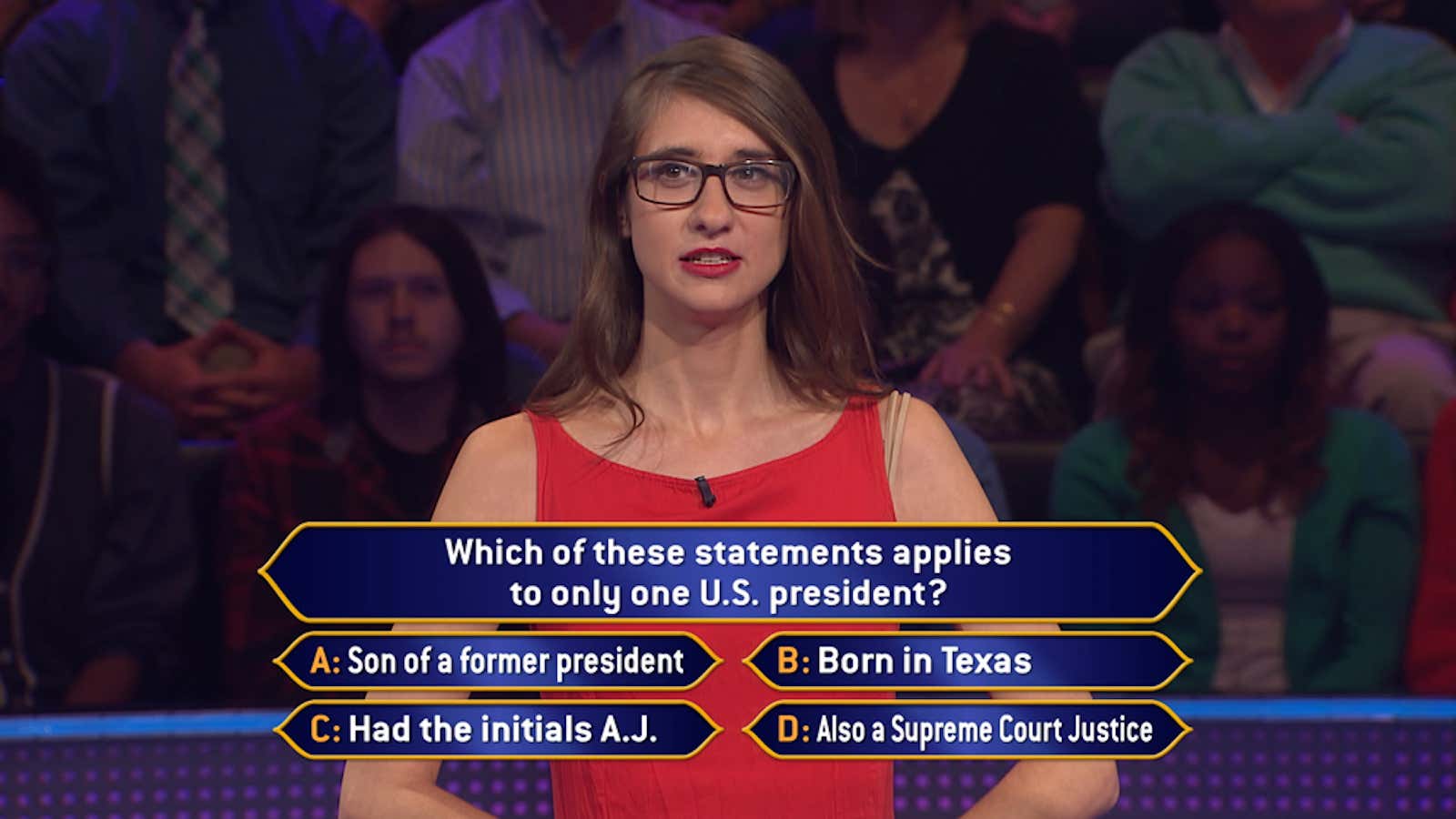

Then I made it to round 2 and saw the $100,000 question:

“With R representing its size, and D representing its potential for destruction, which of the following natural disasters could technically be categorized as an R2D2?”

A) Tornado B) Hurricane C) Blizzard D) Avalanche

I definitely didn’t know the answer, and most people might be torn about what to do here. Luckily, my dad had given me a mathematical roadmap for this very moment.

Thanks to his rules and my practice answering all those questions, my choice was clear. I had $68,100 dollars in my bank. If I answered incorrectly, I’d only get $25,000. If I got it right I’d add $31,900 to my bank. If I walked away, I’d get the whole thing. I could only comfortably eliminate one of the answer choices, so I decided to walk away from the game with a total of $68,100. Not bad for roughly 18 minutes of onscreen work.

I know that most people don’t audition for daytime TV game shows on the regular. But I think there are some universal takeaways here about how to face down high-pressure, scary situations with a lot of unknowns. There are a lot of things you can’t control in life—what kinds of questions you’ll be asked in a job interview, or whether you’ll wind up hitting it off on a first date. But there are always things that you can do to prepare yourself.

For me, what mattered wasn’t just arming myself with facts and data, but also going through the process of preparation itself. By the time I actually played the game, I’d watched so many episodes that I knew the theme music and dramatic lighting cues by heart—so I felt comfortable even in unfamiliar territory. I also knew the host tended to needle the contestants to make them nervous before revealing the answers on the big screen, which made it a lot easier to keep my heart rate down onstage.

I didn’t have a cheat sheet. I couldn’t really change the odds. But just knowing the odds gave me the confidence I needed to perform well under pressure. Because I had the tools to make an informed decision, the game didn’t feel so random anymore.

I haven’t gone on any more game shows since then. But I did move apartments and plan an extensive trip to Europe, both of which benefited from significant preparation ahead of time. When I applied for this job here at Quartz, I combed through more than 100 articles on the site. I looked up every journalist and picked my favorites, so I could talk about their work with confidence. I researched the people I was interviewing with on LinkedIn. I asked my friends who work in journalism for tips, and I did a practice interview run-through with my boyfriend at home the night before. After all that practice and planning, I wasn’t nervous or caught off guard during the interview, and at the end of the day, I got the job.

Now, whenever I’m up against a potentially scary situation, I make sure to dig up as much information as I can ahead of time, learn from other people’s examples, and come up with a specific strategy for success. With the right preparation, it’s a lot easier to give a firm nod when someone asks, “Is that your final answer?”