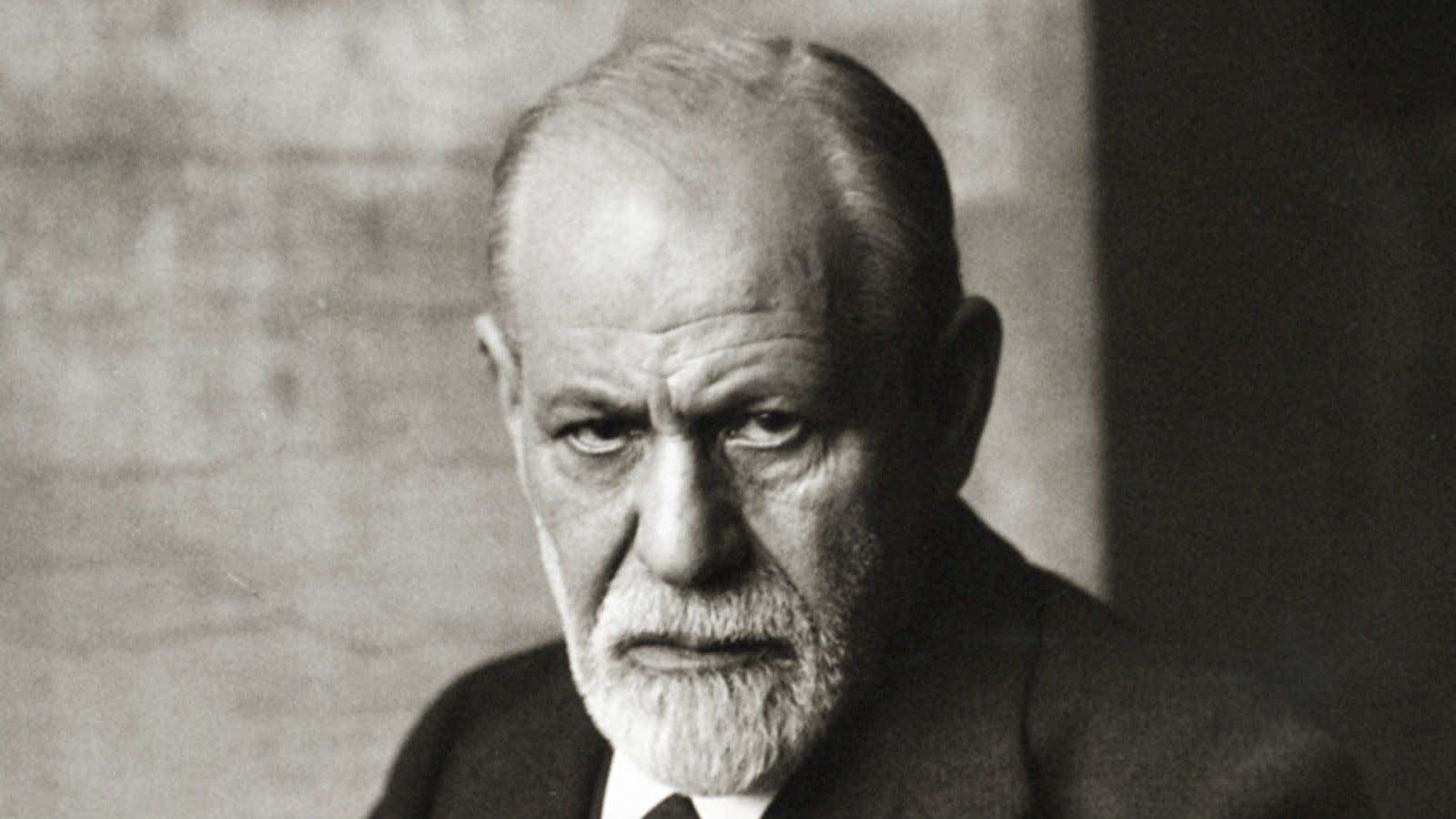

Freudian psychoanalysis is all the range in Argentina. This is the country with the highest number of psychologists per capita and where psychoanalysis is a standard treatment option for kids. So it makes sense that in prisons, too, the inmates get Freudian psychoanalysis once a week.

At least that’s the case in one Buenos Aires prison, where psychologist and researcher Alicia Iacuzzi has headed the program for 30 years. Other mental health services for prisoners have a more Lacanian approach, based on the work of French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist Jacques Lacan, but Iacuzzi believes that Freud provides the best guidelines for prison therapy.

“Lacan writes that the unconscious mind is structured as a language,” she says. “But many of the issues I find here [in prison] are pre-linguistic, and Lacanian theory is not enough to explain them.” And while cognitive and behavioral therapies can change the way a patient acts, Freudian psychoanalysis, which plumbs the unconscious for hidden feelings, works to focus on deeper problems.

Iacuzzi makes sure there are no guards present during therapy, so that the prisoners don’t feel exposed, and says that she’s never had any problems with the inmates.

“People in prisons have been neglected all their lives. So suddenly having a therapist listen to them, give them a space to talk, provides them with a sense of importance that no one, not their families nor society, has ever given them,” she says.

She says most of the prisoners she works with have suffered emotional neglect, and a large number show signs of borderline personalities.

“Emotional neglect and abandonment leave marks on the psyche,” she says. “A lot of patients cry in therapy. I think that me being a woman has a lot to do with that. Even though being a woman in my position is a disadvantage in other ways, it brings up a motherly quality that helps them tap into those childhood pains they haven’t been able to cry for.”

Paternity is another major issue for many of the prisoners, she adds. “A lot of inmates leave their children and their families without a father,” she says. She uses therapy to help them consider paternity and ways to fill their role as a father even from prison.

There are 200 inmates at the Servicio Penitenciario 16 men’s prison, where Iacuzzi offers both individual and group therapy. She starts every day at 7am with group therapy sessions for the guards, which began after one guard complained that if the inmates were offered psychoanalysis, he wanted some, too. Prisoner group therapy lasts an hour, from 8am to 9am, and Iacuzzi and her colleagues then run private sessions for the rest of the day. Around 80% of the prisoners want therapy, Iacuzzi says. She aims to offer a weekly session to each, but occasionally her schedule fills up and she can only provide appointments every other week. There are also open clinics at Christmas and New Year.

Iacuzzi says she makes a point of developing a rapport with the prisoners, which might account for some of the demand.

“I receive everyone who is admitted to the prison, so I get to interview them and get to know them from the start,” she says. “And I don’t just stay in my office. I walk around and speak to the inmates, the guards, the doctors. And that’s how I get everyone interested in visiting my office.”

A humanitarian approach also helps. “We try to see past the crimes the inmates have committed, and try to focus on the part of them that is healthy,” she says.

Iacuzzi says her program is far less bureaucratic than the mental health services in most Argentinean prisons, and that the government is interested in using her model as a pilot to potentially expand to other prisons in Buenos Aires.

Translation work by Felicitas Sanchez.