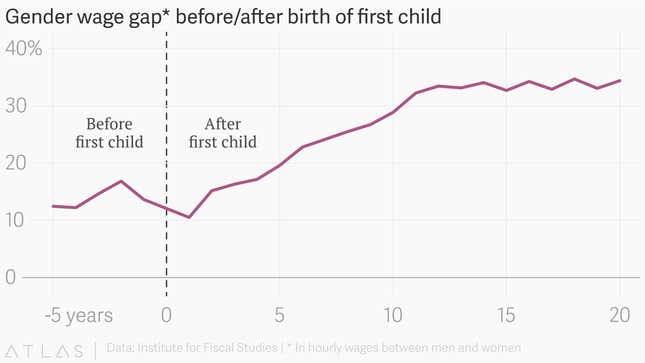

Motherhood doesn’t pay, at least in terms of wages.

Before women have their first child, the wage gap in Britain between them and equally educated men is about 10%. By the time that child is 12 years old, the gap has widened to 33%, according to a new study published today by The Institute for Fiscal Studies in Britain.

The differential is not immediate, but builds up over time. “What is striking is that the gap takes off in the years after they have their first child,” said Robert Joyce, one of the authors of the study. “It’s not an immediate effect.”

One reason mothers earn less is they work less once they have a child. By the time a mother’s first child is 20, women have on average been in paid work for four years less than men. They have spent nine years less in paid work of more than 20 hours per week, the study shows. As a result, they miss out on critical wage progression opportunities, Joyce said.

“The Gender Wage Gap” also found that the pay gap has been closing more rapidly over the past two decades for those with less education, but has remained stagnant for those with mid- and higher levels of education. (In Britain, GCSE’s are important exams given to 16-year-olds which also act as qualifications for jobs; A-levels are given at the end of high school and can be used for college entry).

This may be due to the implementation of a minimum wage in Britain in 1999, Joyce said, which would have helped equalize pay for both men and women with lower levels of education. “We don’t know for sure why there has been no progress for the higher-educated groups, why that gap hasn’t come down,” he said.

There has been some progress. The hourly wages of female workers are currently 18% less than men’s, on average, compared to 2003 when they were 23% lower. Women have more rapidly increased their level of education compared to men, overtaking them during the 2000s in educational attainment.

The study used two data sets: the Labour Force Survey (LFS), which includes data on employment and is the largest household survey in the UK; and the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), a long-running survey that follows the circumstances of the same sample of people over time.

Comparisons between earnings of men and women show the big economic price that women pay for being their children’s main caregiver. The gap in pay between men and women is only 10% for those without any children, but it is 36% on a weekly basis for men and women overall. That’s partly because men work more hours; the hourly pay gap is 16% for men and women who work more than 20 hours a week.

Working part-time or taking time off from work to have children reduces earnings permanently. Hourly wages for women who return to work after having a child are, on average, about 2% lower for each year that they have been out of the workforce. Highly-educated women who worked more than 20 hours a week saw hourly wage growth of 4.1% (above the wage growth associated with the economy); highly-educated women who worked half-time saw, on average, no wage wage growth beyond what the economy would predict.

Joyce said that policy measures to address the gap should focus on how to improve wage progression for people in part-time work. Part-time workers could be offered additional training or given more chances to participate in informal networking and mentoring. Better support for childcare would enable women–and men caring for children–to continue working full time.

So as long as we are all childless and able to work lots of hours, everything should be fine.