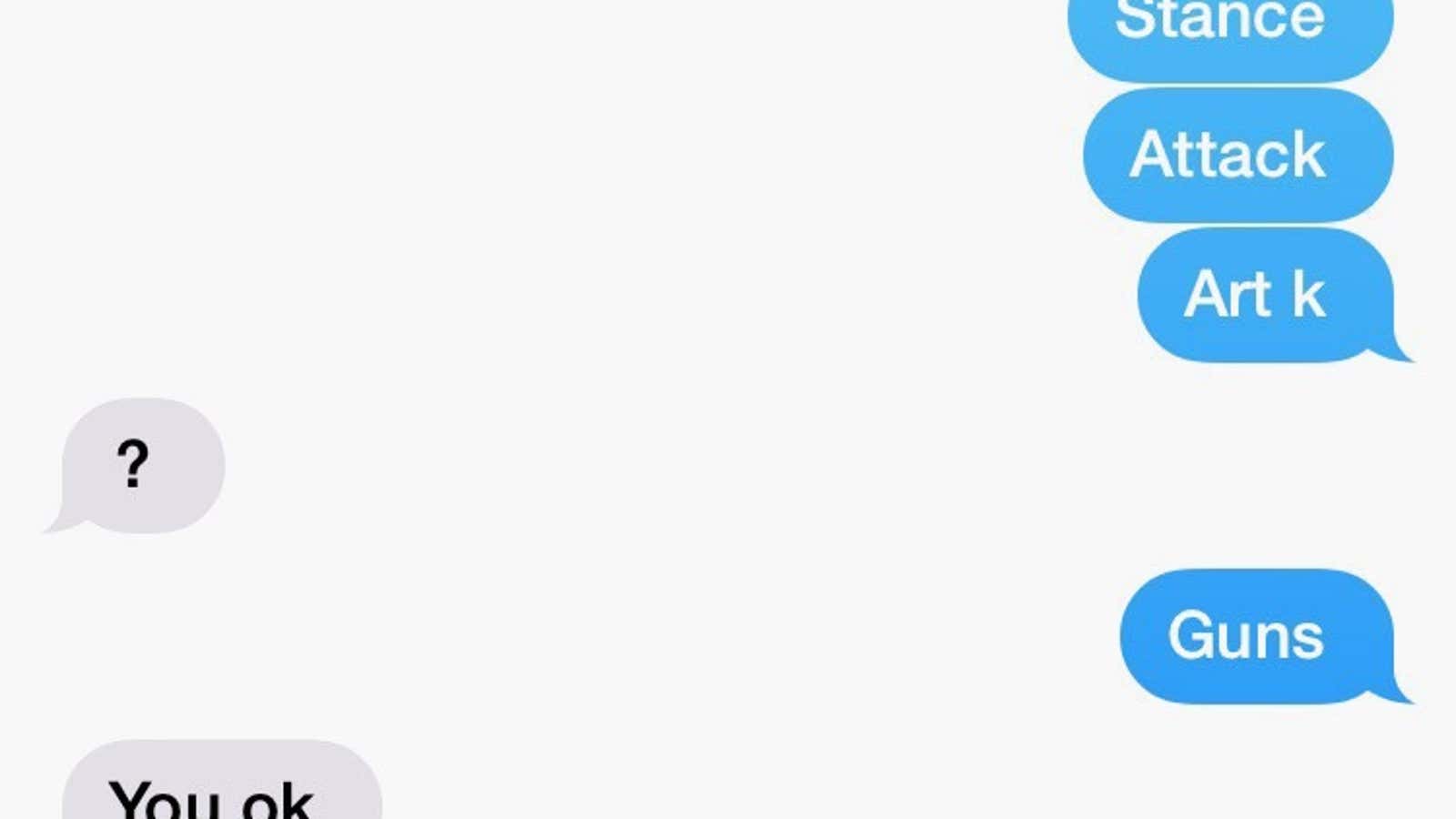

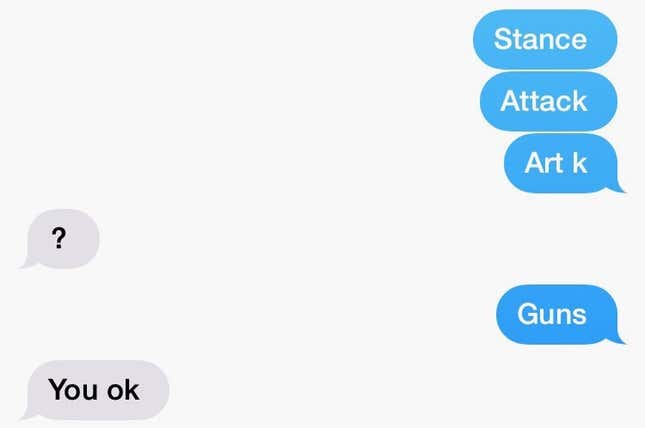

Imagine receiving a text like this:

The experience

I was traveling to Malmö, Sweden to give a talk at a conference on “Building an Empathetic Company” by way of Norwegian Air via Copenhagen. It was a red-eye flight scheduled to leave at 9:55pm.

Since it was the first time I had flown Norwegian and I couldn’t check-in online, I left for the airport with plenty of time. At 7:30pm on a Sunday night, Terminal 1 was busy but not hectic. Norwegian had a long line and a shorter one for passengers with no bags to check. I had a duffel, so I went to the short line, got my ticket, and made it through security quickly.

I stopped at a restaurant in-between Gate 4 and Gate 6, had dinner, and read. When 9:15 came around, I paid my bill and walked to Gate 7 to board my flight. The crowd loitered, waiting for instructions, until the gate agents announced the flight would be delayed an hour. So I walked around looking for a seat that didn’t feel claustrophobic.

I’m telling you this, because where I ended up sitting made a difference.

I chose a seat to the far left of the terminal in the last aisle of Gate 8 where there was nothing but open space and a food stand. I figured I should do something productive, and started to write out goals for the upcoming week to share with my team. I was immersed thinking about the week ahead when a piercing alarm filled the terminal.

* * *

Lights above the terminal gates started blinking a long pronounced floodlight warning, and lights on the ceiling darted in a hurried blue and white whir. I realized the alarms had been going off as I typed and that they had either gotten louder, or it wasn’t until others around me began to notice and react, that their message reached me.

People started to scream.

“What is happening?” I asked myself.

I watched as people darted through the terminal towards me. I put my carry-on on my back and grabbed my duffel with my free hand. Phone in the other, I tried to open the camera app as I backed up against the window a few seats away.

The screaming became deeper, and echoed through the terminal.

I remembered thinking, “Men are screaming too” as I managed to swipe to video, bent down behind a row of seats and began to film.

I did this for exactly 16 seconds, before I realized something was wrong. Very wrong.

The video shows dozens running for the emergency exits. What it does not capture is the scale of what happened next.

I think so few videos were shared from that night, because people were too afraid to even think about filming

* * *

As I dropped my phone, a stream of people came at breakneck speed through the terminal.

There was another wave of piercing screams and the echo of people running.

It was a stampede of people. It was like the terminal had been lifted vertically and people were falling like checkers on a Connect Four board, slamming into a pile at the exits.

I let my duffel fall and surveyed the room. I could cross 100 feet to a door where people were crowding, or another 200 feet to either corner of the terminal where dozens more were pushing their way out.

It registered that the last two exits at the end of the terminal were better. They had bigger doors.

* * *

Another wave of screams filled the terminal. I dropped to my stomach and slid underneath the aisle of seats. To my right, many people were doing the same. To my left, I watched as a woman hid behind a waste bin. She was bigger than the square recycle/trash canister, and as she banged herself into it, it skid and reverberated.

It was the same reaction a caged animal has when a trap slams down. It wants to get out. Every cell in its body moves at an incredible speed to fulfill this desire. It cannot feel pain as it hits against metal.

I looked down at my own hands. My right hand gripped my phone and my left was shaking. “Was I afraid?” I asked myself.

* * *

Interrupting this thought a sound filled the terminal.

“POWH. POWH. POWH. POWH. POWH.”

Gunshots.

Or was it clapping for Usain Bolt’s gold-medal victory?

Or was it the sound of line separators that direct traffic at Security, falling in cacophonous succession (all the way back before the gates began)?

Or maybe the sound of joints exploding off a door?

None of these media-suggested alternatives occurred to me.

It was gunfire. To me. To many others.

* * *

My brain searched furiously for an explanation. “Where is security? Where the F#&*! is everyone?” Lying flat on the ground under the seats, I locked eyes with a Filipino man and his young daughter. His eyes were bulging and he uttered one statement on repeat.

“Oh god. Oh god. Oh god,” as he pulled his screaming daughter beneath him.

I looked at his daughter and whispered, “Shhhh… It’s Ok…Shhhh.”

A cacophonous scream erupted in the terminal moments after the shots fired. I looked with others out onto the empty aisle of the Terminal.

We were waiting for the person that had fired to emerge, a group of people even. To make demands, or maybe no demands at all. Maybe just make a point.

* * *

People have asked me what it felt like. I think this is the first time I understood what the word “terror” means to so many people who have really experienced it.

Yes it was scary, but that’s not good enough. Imagine being in the desert and a wild animal is chasing you, hell-bent on ripping every limb off. It’s that, and the realization that this animal is not acting on basic predatory instincts. This animal is a human, and it wants to hurt you.

It’s a deeper level of fear because your mind can not comprehend it. It is in complete disbelief. A state of terror.

Your mind goes to 9/11, Orlando, Columbine, what your buddy must have felt in Afghanistan. In the moment, you reference these other events.

* * *

No security came. No announcement. Just chaos. I had no doubt at the time that in that moment, my life was in my own hands.

* * *

Quiet overcame the terminal for a moment. I became aware of the feeling of my stomach against the ground. I surveyed the three exits again and not consciously, but with my feet, made the decision to run for the far right doors. I ran across dropped food; a giant soda cup; ice avalanched; Coke all over the floor. There were hundreds of things everywhere, computers, bags, shoes, jackets.

Things were still spinning from the wave of people that had just kicked their way out.

* * *

Why did I run? There was an overwhelming feeling of being trapped. There was a window of opportunity, and since I could not see the perpetrator, there was still ambiguity on the outcome, and maybe the opportunity to escape. We were in danger.

I felt like a deer bounding across an open field, hoping the hunter was looking the other way.

* * *

I ran 150 feet, did a running jump over a row of chairs and ran other 20 feet through open doors.

I ran with others into a wide cement stairwell. A pilot and two flight attendants crowded in the corner, staring at the running crowd in nonplussed confusion. They grabbed their wheelie bags close, seemingly unsure what to do as people whizzed by them.

“Go down the stairs!” my brain told me.

I watched a man help another man hop down the stairs, limping and jumping down the steps as if he had sprained a ankle.

Their faces communicated fear, “We are not moving fast enough.” The exit stairwell was wide and people rushed down, toppling, getting up again and running.

Now one floor down, I had a choice. “Get out on this level? Get out here? No. Keep going. Get outside.”

* * *

I ran through the doors out onto the airport runway into a crowd of hundreds and hundreds of people. People around me darted across the tarmac. Hundreds of people huddled along the terminal walls as planes landed. I looked around for security.

“What are we doing? What is going on?”

More people raced onto the tarmac from behind me. I watched people hide in luggage trolleys, under cars, by the wheels of planes. Most of us kept moving, some with rolling bags, many with nothing. Shoes were missing. People were running in torn tights. We made our way in fast procession to the farthest corner of the tarmac near what would have been Gate 1.

The crowd seemed to be asking the same thing, “Are we safe?”

There were men in yellow, reflective vests who were unsure what to do—“Stay right, keep moving”—one said quietly.

Near the Arrivals door under Gate 1, Port Authority police screamed into their walkie talkies. They gestured for us to wait. I turned my face to my phone and opened Twitter. I had bad reception, but I tried to share an update.

Then the quiet. People crowded. One man near me opened a pack of cigarettes and lit one. People around him jumped at the sight of flame. I took a picture. We waited. Then the cops announced, “Ok, out these doors.”

The crowd started to move forward slowly. It didn’t feel safe yet.

Security had expressly not said, “Everything is under control.” They didn’t know. And this was being communicated in what they said, and what they hadn’t. Letting children and their parents go first, I stood next to the man smoking a cigarette; he dropped it to the ground, darted forward, and ran to the top of the line.

Without warning, screaming erupted, and the crowd that was exiting peacefully into the airport exploded. There was a quick shoving match between a frantic outgoing crowd and the ingoing procession and then instantly, everyone changed direction.

“OUT!” People stampeded out the doors, terror on their faces. A woman fell, her knee gushed open. The crowd dispersed along the sides of the tarmac.

Security ran too.

I hid behind the back of a van in the corner. Others huddled around me. A few minutes passed. Crowds started to descend from planes 500 feet away. They were standing and sitting in orderly squares. Slowly, people started to stand up near me as two security guards emerged and told us—once again—to make a line to leave the asphalt tarmac to the ground floor of the Terminal into Arrivals and Customs.

A woman from Sweden with her son, asked the police—“How do you know it’s safe?” She had just watched people stream out in terror.

Still behind a large Homeland Security van, I stood on the bumper to watch what was happening. People started to file into the terminal.

“Ok. I can go too.” I thought. I jumped off the bumper to the right of the van and began to make my way to the door when a scream erupted and for a second time, dozens came running out the door stampeding into the exiting crowd. I hit the floor again, and shuffled under the van.

Others would ask me why I choose to go under the van. “Was it smart? What if a cop suspected me?” All I can say is in that moment, I had watched people run for their lives in five separate waves.

There was no feeling of calm, or evacuation.

This wasn’t a fire drill.

I remember looking down and watching a large ant walk past me. I stretched my feet and lay them flat on the ground, pressed my hands against the gravel like a pose in yoga, ready to push out from under the car. It still wasn’t safe—people ran around me. It got quiet again, and I sent texts to several people including a friend who was a Navy Seal inside the terminal, who would later be quoted in the the New York Times as saying:

“I’ve been to Iraq and Afghanistan, and I’ve never been in this situation where you’re in a massive crowd and there’s nothing you can do.”

and in his own blog he wrote:

“I was confident that I was in charge of my own destiny at this point.”

* * *

Many minutes later, a cop flashed a light under the car and asked me to come out. I obliged, and sat on the curb with others.

* * *

I went to Twitter to look for any answers on what was happening. No statement issued seemed to reflect what I was experiencing. Twitter trolls were out and active.

It surprised me that as I was currently still experiencing what was happening at JFK, people continued to tweet at me that “there was no event.” Another twenty minutes went by before we walked through the doors of Arrivals. Baggage Claim and Customs where mobbed.

Who knows how many people went through Customs without showing their passports? Passengers would later recount watching a stream of people, at least 40 people, running through Customs to the curb of Arrivals. This is significant, but not reported.

Bags and shoes were scattered throughout Baggage Claim. People were starting to line up again, but there was no real order, or clear direction. One guard asked me what flight I was on and led me to the front of the line at Customs. The white-faced security guard asked my name. He typed on his computer and seemed to look at a manifest and waved me through, not even making eye contact.

Inside the terminal

It seemed like we were free to leave. The Navy Seal texted me that he was already home in the city. My bag was still in the terminal, and passengers whispered to each other that flights were still leaving. Eventually a guard asked us to stand in line to go through Security.

Terminal 1 TSA stared the crowd down. They spoke amongst themselves, and cracked a joke or two to release the tension. They tried to ignore passengers asking them what was happening. An airport security guard or gate agent told us to form a line. I waited in one line or another for four hours, waiting to retrieve my bag from the terminal. I would get home from the airport at 5am.

Exhausted. Adrenaline. Waiting in those lines, I watched Twitter and the media form a perception of what had happened.

There was no mention of Terminal 1—as if everything you just read was a figment of my imagination. Passengers were exhausted. I think most people were too in shock to exchange experiences. The terminal was very, very quiet.

Many of the media reports that night and in the following days used the word hysteria. I would describe the feeling differently. It was a feeling that did not end until 11:48pm for me. More than 90 minutes after this all began. Internalize that.

For 1 hour and 30 minutes, I and others in this major American airport, in 2016, were in a true state of terror.

Did we terrorize ourselves?

If you saw the news, the headlines and message communicated “no big deal, move along.” That was not my experience. It was a big deal to me and hundreds of fellow passengers at JFK that night.

I shared my experience because I think it’s important to put it out there. It should make people uncomfortable.

And not because it was scary, but because it’s scary how much of a discrepancy it is to what was officially reported.

At the end of the day, I went home and then got on my flight the next day—exhausted and a little shaken—but just 24 hours later, I was back to living my life.

We live in one of the greatest, safest places that’s ever been and it’s our responsibility to uphold that greatness and safety.

We do that by demanding better journalism—real stories. Reading long form. Opting out of pablum, and listicles, and puffery on blog sites. The cursory reporting that came out on this event simply wasn’t good enough, and people didn’t ask enough questions before playing Monday morning quarterback on the social sphere.

We are our own editors these days, and if we only read “How to Launch a Startup in 3 Easy Steps” we start to lack empathy for the world as it really is.

In fact, I believe our reactive behaviors on social media—drowning ourselves in opinions, knee-jerk reactions, insults, and trolling even by would-be-presidents—are eroding our safety more than any single bad actor can.

Do not let feelings unsubstantiated by true facts grow into into a toxic force that dissolves the fabric of our society

We must learn together. We have to set a higher bar for ourselves and our institutions.

We can’t let fear stop clear and transparent communication from authorities to the public. Suppressing, downplaying, or avoiding isn’t the safe or smart move. We can be thoughtful and positive. I do not expect our institutions to be perfect, but we need to learn. Let’s make a plan to fix the clear failure in the response.

The media should not let the story fade away.

How is it possible that with so many people in the airport, no account like this has been shared outside of the New York Magazine account?

Reporting is a noble job—I hope it continues to attract great people to take on the challenge.

Finally we have to be better humans, please.

Get off the junk food diet of cursory reporting, PR masked as news, and non-fact-checked opinion threads. The people who control the news control perception. In many ways we are more in control than we’ve ever been. The papers of yesterday may not be able to afford deep reporting, so we need to do it ourselves and demand better with our attention and wallets.

Ask for real news—give your attention to what counts. Please exercise restraint and open mindedness and decorum. Or if that’s too much, just treat people the way you want to be treated.

There is a raw, exposed nerve in the public from the divisiveness of our discourse. America is great, when it acts greatly.

And to take it full circle: We all need to practice a hell of a lot more empathy for others and ourselves.

We have to be active in our society. We have to vote. To stand up for what is right. Next time it could be life and death—as it easily could have been this time.

If we don’t learn from this experience, we have in fact terrorized ourselves.