The UK government collides with the changing global consensus on austerity

The international austerity soap opera rolls on in the United Kingdom today (May 22), where the International Monetary Fund will critique (paywall) the government’s economic plans as growth-hindering.

The international austerity soap opera rolls on in the United Kingdom today (May 22), where the International Monetary Fund will critique (paywall) the government’s economic plans as growth-hindering.

There, chancellor George Osborne, perhaps the most important advocate of tax hikes and spending cuts to spur the economy, has spent the last two weeks jousting with representatives from the IMF, the previous title-holder for austerity defense. Previous, because the institution has undergone a recent shift in position.

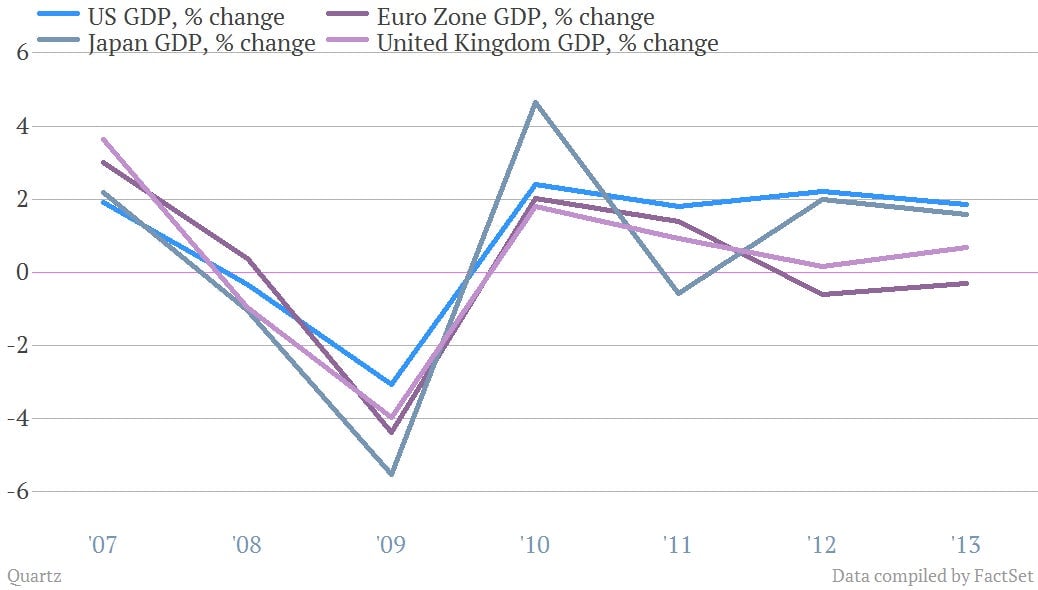

The two weeks of meetings came as part of the IMF’s “Article IV” consultations on the economy that it holds more or less regularly with each of its 188 member governments. Since the recession, the UK hasn’t had much luck getting steady growth, instead dipping toward recessionary territory:

In 2010, Osborne and prime minister David Cameron launched a policy of spending cuts and tax hikes with the hopes of cutting the UK’s debt burden (the ratio of debt to GDP), lowering borrowing costs, and returning the country to economic growth. But after several years of this policy, they’re still missing their targets for the debt burden:

When you cut spending (as Osborne has since the recession), it reduces borrowing and can therefore shrink debt, but it also cramps growth, so the ratio of debt to GDP may not get smaller. In defense of Osborne and Cameron, it’s not all fiscal policy: the UK’s vital North Sea oil industry suffered setbacks, and the UK’s big finance industry suffered in the 2008 crash and the euro crisis.

But even so, the UK was recovering more slowly than economies hit by financial crisis in the past. When IMF officials met with the UK government last year, they warned (pdf) that “scaling back fiscal tightening plans should be the main policy lever if growth does not build momentum by early-2013.”

In March, Osborne offered a new budget that includes a tax cut for businesses and an increase in the country’s income-tax exemption. But, by and large, the budget does not “scale back fiscal tightening”—it aims to keep public investment at low levels while ginning up housing investment (comparisons to America’s Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are not welcome) and counting on incoming Bank of England governor Mark Carney to save the day with easier monetary policy than the current governor, Mervyn King.

Osborne’s push to reduce borrowing is part-and-parcel with conservative politics in the UK. It was also, when he kicked it off, part and parcel to the IMF’s recipe for countries with high debt and low growth. As countries like Greece saw their public finances unravel, the fund was happy to advise austerity.

But in the five years since the recession, and particularly as economies that provided more stimulus seem to have had more success growing and controlling debt—at least for now—the IMF has reconsidered. The most obvious example was a paper earlier this year from its chief economist, Olivier Blanchard, outlining what he saw as technical errors in the fund’s forecasts for austerity. Basically, Blanchard said that the fund initially thought Osborne’s approach would work. After watching it play out for a few years across Europe, though, the fund’s economists find it to be far less effective at creating growth than they thought.

But that’s something that Osborne himself isn’t ready to admit. His platform for the 2015 elections is to target cuts on the mandatory spending in the UK’s budget, particularly welfare costs, which makes this a bad time for the IMF to be changing its mind about what happens when you do that.

Add in the recently discovered problems with prominent American research suggesting that high debt burdens are bad for growth, and Osborne faces a perfect storm. The IMF will urge the UK to be more fiscally flexible, just as it has urged the US to slow the pace of its deficit reduction. Osborne is expected to resist. But it’s doubtful that this will convince the global bureaucrats, or even the UK’s electorate: In 2010, his programe predicted 3.5% growth this year in the UK, but current forecasts are around 0.6%. If that doesn’t demand a re-think, what does?