To the average observer, it may seem as if the Spanish language is secure in the US. After all, there are now even more Spanish speakers in the states than in Spain. On television, Spanish-language networks are drawing top ratings. In schools, Spanish language immersion programs are skyrocketing. And many state elections provide Spanish-language ballots. With the total Hispanic population in the US, including undocumented residents, projected to reach 29% by 2060, is Spanish becoming our linguistic futuro? Not so, according to sociologists.

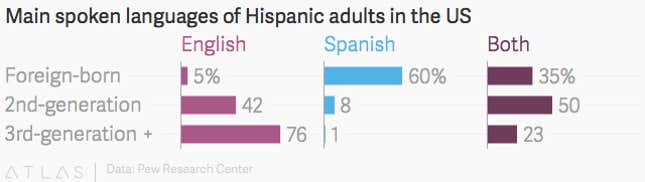

In the US, studies have found that Hispanic immigrants fully assimilate linguistically within about two generations. Many of the first generation arrive in the US as monolingual Spanish speakers. They bring up their kids as second-generation bilingual speakers. And when those bilingual speakers have kids of their own—the third-generation grandkids of the first, monolingual Spanish speakers—they wind up becoming monolingual English speakers who, at the very best, can understand, but not speak, their grandma’s español. Sociologists from California to Florida are quick to remind us that the US-born Hispanics “seldom pass on Spanish to their offspring.”

As a result, the Spanish language in the US is constantly under threat of being phased out, family by family. In a 2004 sociolinguistic study, “(Language) Shift Happens,” researchers notes that if no new Hispanic immigrants were to enter the US, Spanish monolinguals would literally die out within the century.

And this might be on the horizon: While the Hispanic population in the US is still growing, the growth is mostly through second- and third-generation familial expansion, not through fresh immigration. In 2014, 35% of Hispanics were foreign-born. The US Census Bureau predicts that this number will fall to 27% in 2060, and stateside births now drive 78% of Hispanic population growth in the US. The stagnation of Hispanic immigration can be attributed to less-favorable American economic conditions, tighter border controls, and the deportation of undocumented workers back to Mexico.

Even when immigrants are concentrated among urban areas in what the same researchers label “sociolinguistic domains,” the linguistic assimilation process is unfettered. Interestingly, researchers also make the case that a loss of stigma associated with limited english proficiency has not increased the longevity of heritage languages across generations: Even among Mexican immigrants in Southern California, linguists estimate that 97% of their third-generation American descendants will speak no Spanish at all.

These kinds of linguistic shifts are not unprecedented. According the the Pew Research Center, the immigrant share of the US population peaked not in contemporary times, but at the turn of the 20th century when there was a boom in European immigration. Languages like Italian and German were widely spoken at the time. These languages are now far less common in US neighborhoods, and it’s reasonable to think that Spanish may face the same fate.

Spanish is certainly not an “endangered language” by any standard. But as its popularity fades in the future US, it’s worth considering what new languages may rise in its wake. The 2011 US Census reported that the most common languages spoken in US households are currently English, Spanish, Chinese, and Tagalog. In the same way we have seen the rise and fall of Italian and German and are currently witnessing the same trend with Spanish, immigrant populations from China and the Philippines may provide the next phase of the US’s lingual history.

“This is a country where we speak English, not Spanish,” Donald Trump asserted in a Sept. 2015 Republican debate. In a few decades, he unfortunately may well be right.