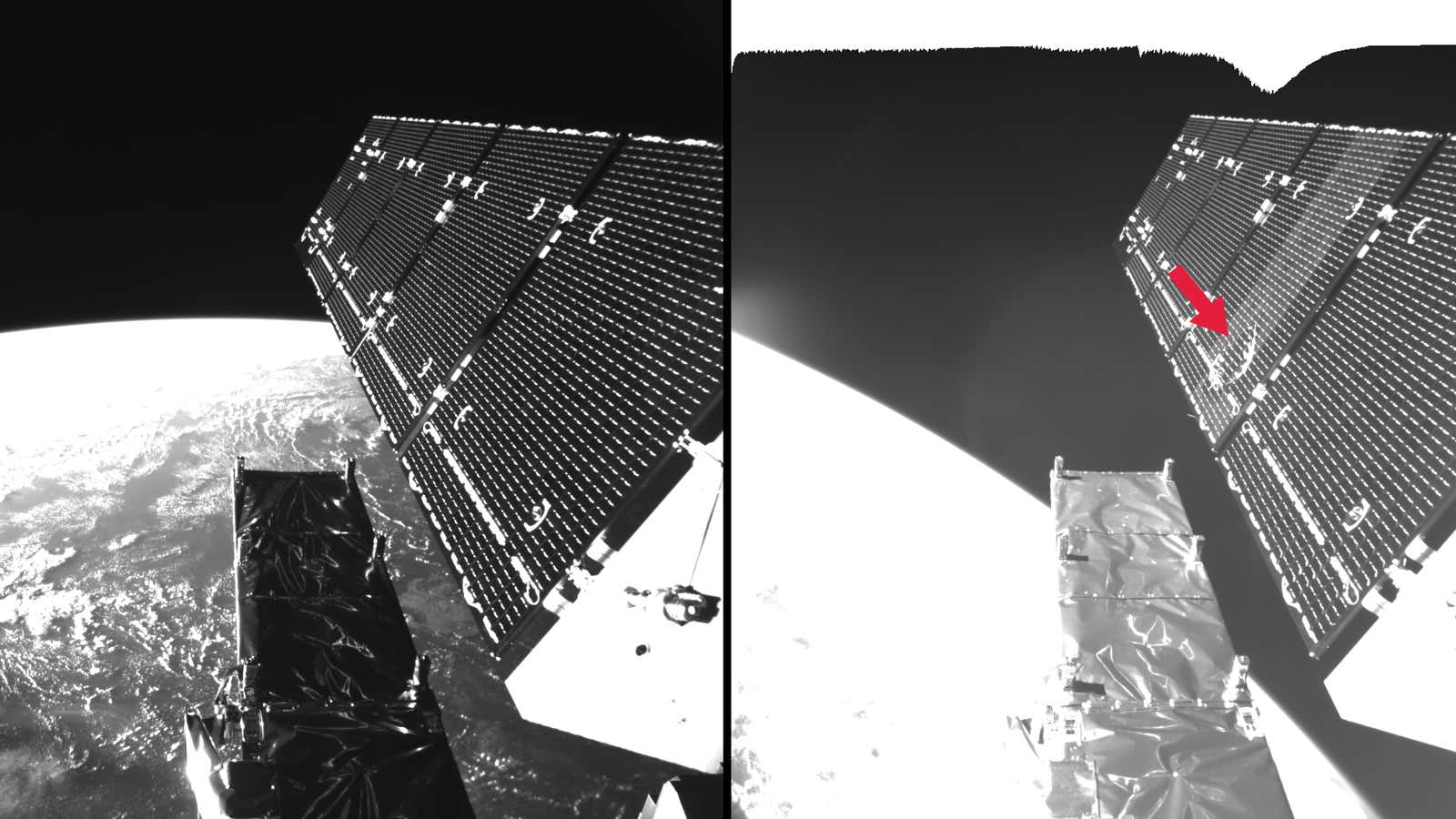

On Aug. 23, engineers at the European Space Agency spotted a problem. A solar panel on the Sentinel-1A satellite, which does routine environmental monitoring, had been hit by space debris.

With help from onboard cameras, the engineers believe what caused the damage was perhaps a millimeter-sized particle. The damage caused, however, was about 100 times its diameter.

At present, NASA is tracking more than 500,000 pieces of debris, or space junk, orbiting the Earth at speeds of more than 17,500 mph (28,000 kmph). They range from the size of tennis ball to a tiny marble. But most debris, like the one that hit Sentinel-1A, are too small to track and that’s bad news.

“The greatest risk to space missions comes from non-trackable debris,” says Nicholas Johnson, NASA’s chief scientist for orbital debris.

The trouble is that the problem of space debris is likely to get worse, even if we stop sending more objects in space around the Earth. That’s because the objects that are already up there will slowly disintegrate and form smaller particles, which may collide with one object and create more particles and so on. This could cause collisional cascading, and it was the premise of the movie Gravity.

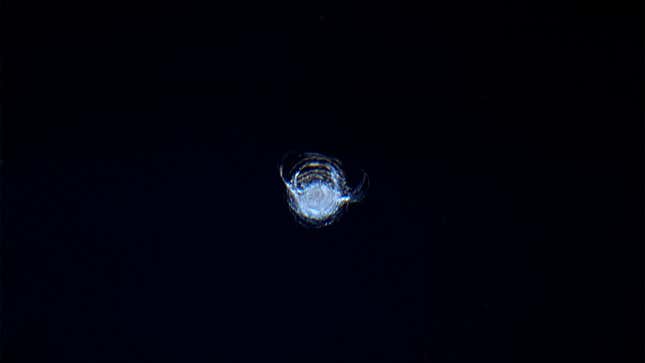

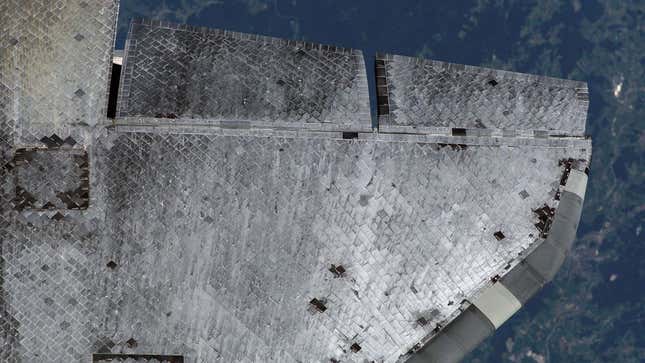

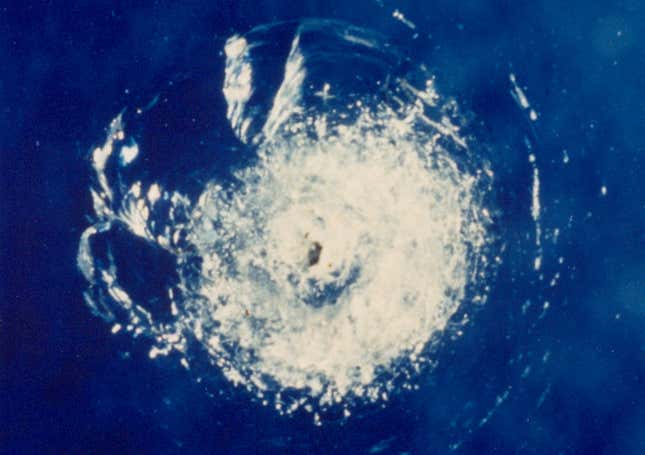

The only solution is to find ways to actively remove space debris, and we are starting to think how to do that. Here are some past examples of what spacecrafts look like when hit by minuscule space debris at incredible speeds.

Fortunately, Sentinel-1A is still fully functional.

But as we put more space debris in orbit around Earth, we are increasing the risk of causing severe damage to valuable space assets that help us do such useful tasks as using Google Maps to navigate your way home, or even space missions, such as sending rovers to Mars or supply missions to the International Space Station.