A data-driven approach to journaling shows you how to track and analyze emotions with pen and paper

The Fitbit has nothing on the common notebook.

The Fitbit has nothing on the common notebook.

A new book takes the quantified self one step farther by returning to the page. Dear Data, released Tuesday (Sept. 6) by Princeton Architectural Press, shows how a friendship unfolded between two women who corresponded weekly for a year through hand-drawn data visualizations, sent by snail mail.

The project captures a distinctively modern obsession with personal data collection, and self as laboratory, and combines it with the mindful-ish-ness of coloring and counting grains of rice. Dear Data teaches readers to see themselves as data collectors, and offers instruction on how to process, analyze, and draw visualizations based on data from your life.

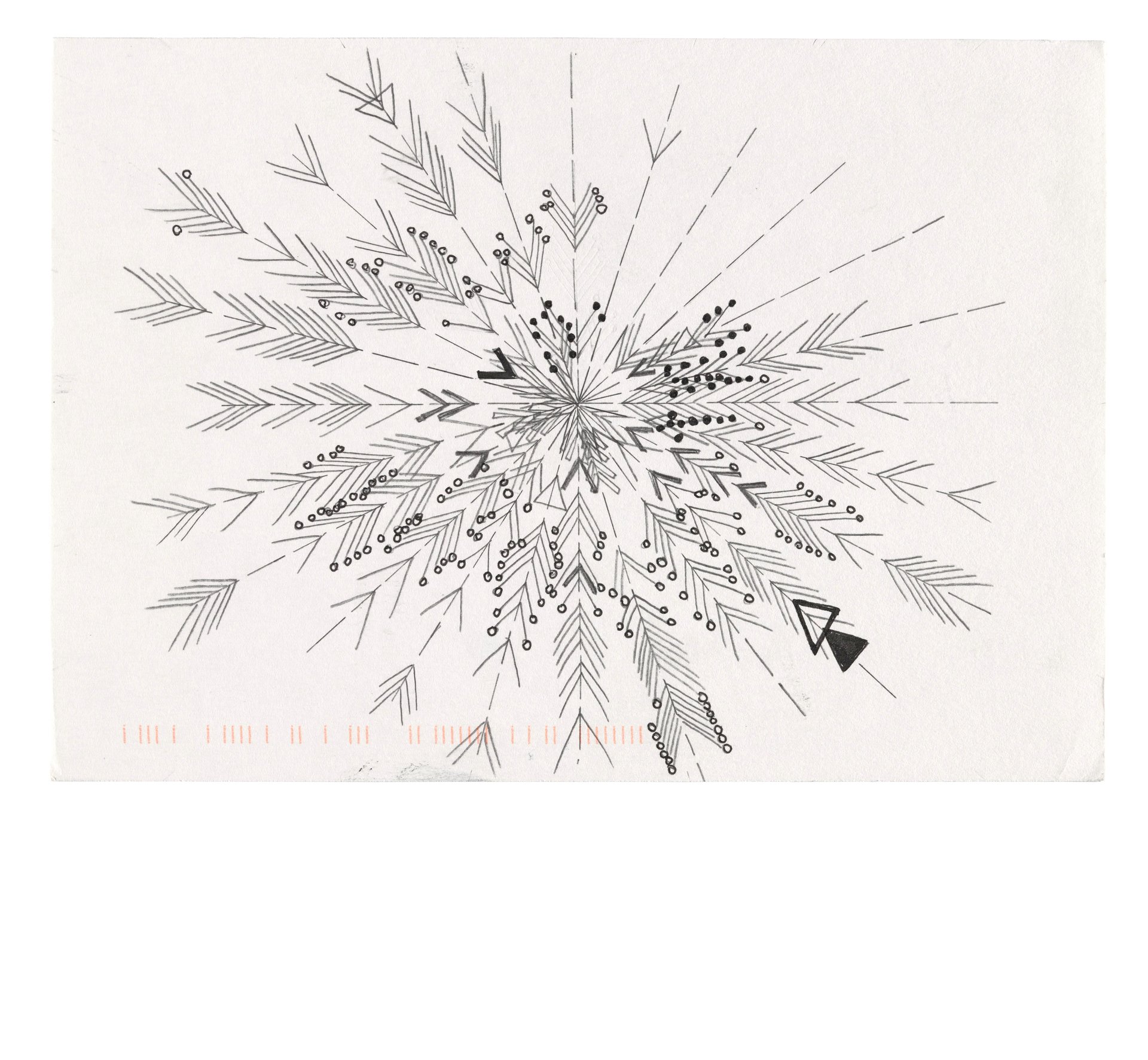

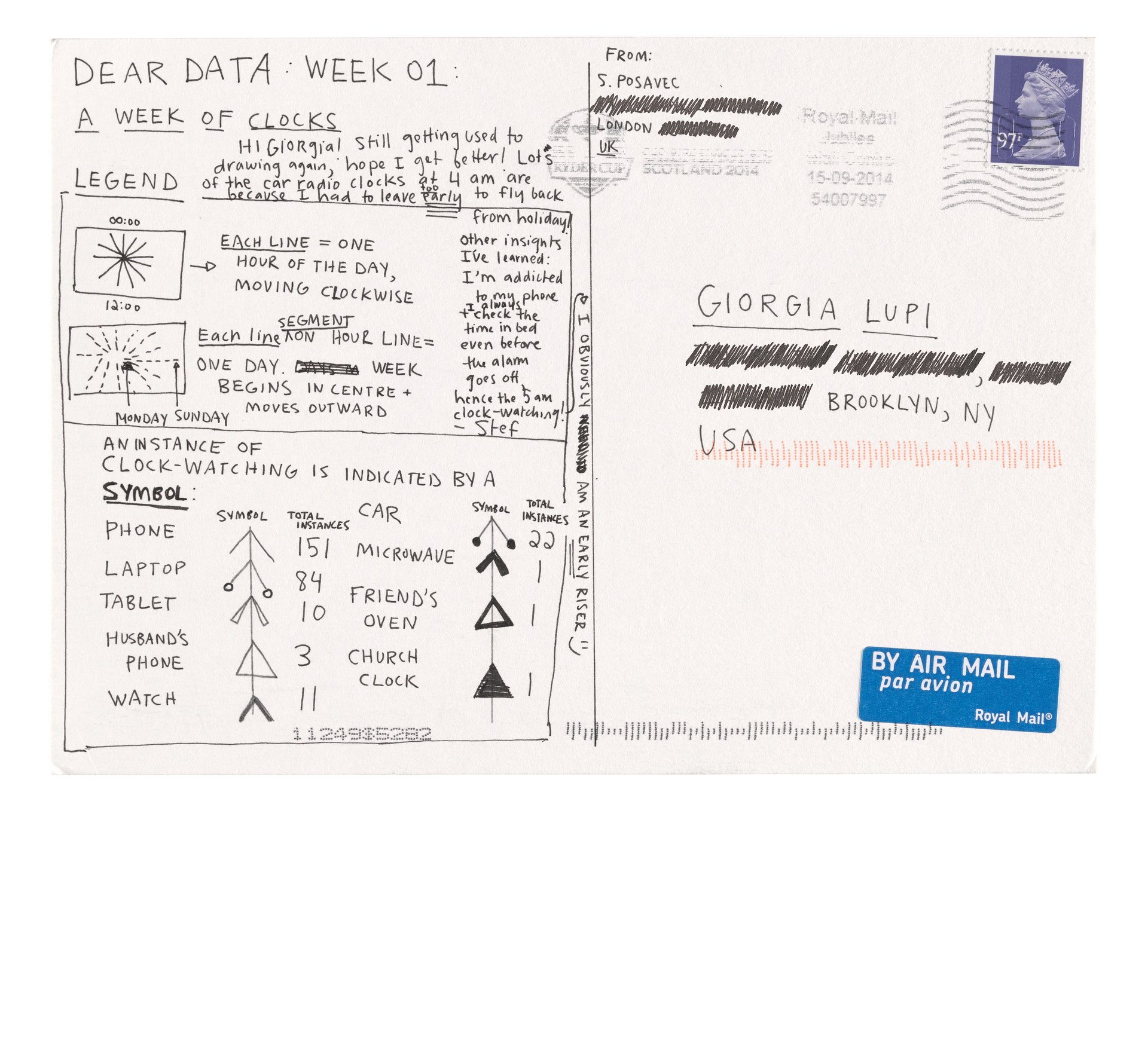

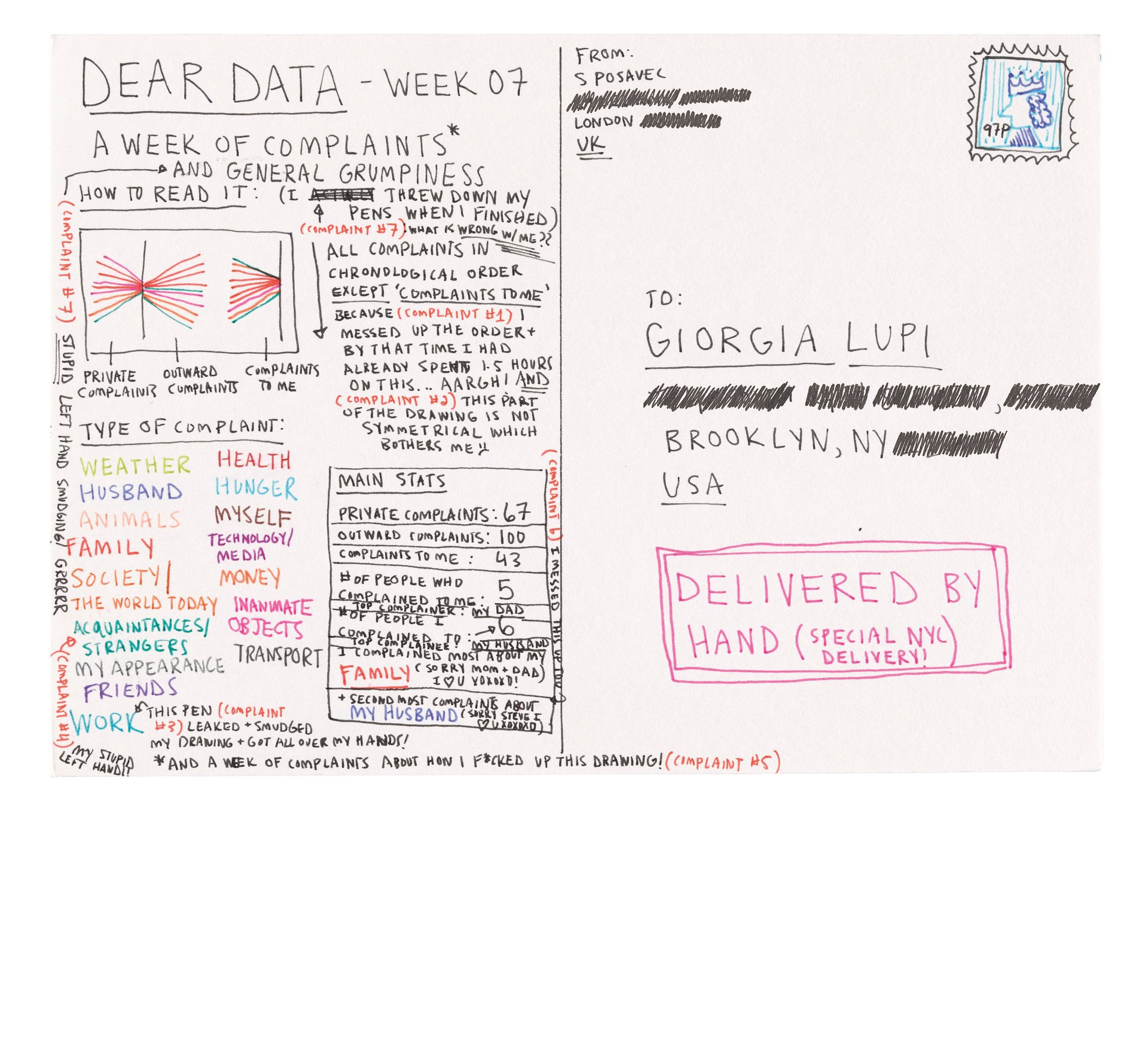

Starting in September 2014, designers Giorgia Lupi and Stefanie Posavec sent each other postcards from New York and London, respectively, with illustrations that answered a shared question. The two, who had met at a conference, learned about one another a week’s worth of information at a time: a week of phone addiction, a week of drinking alcohol, a week of thank you’s, a week of looking in the mirror, a week of swearing, a week of laughter, a week of apologies.

Lupi and Posavec each interpreted the week’s prompts separately, and spent their days diligently collecting personal data, before sitting down at the end of the week to draw by hand what they’d collected. On the back of each postcard, they provided the other with a key on how to understand their detailed systems.

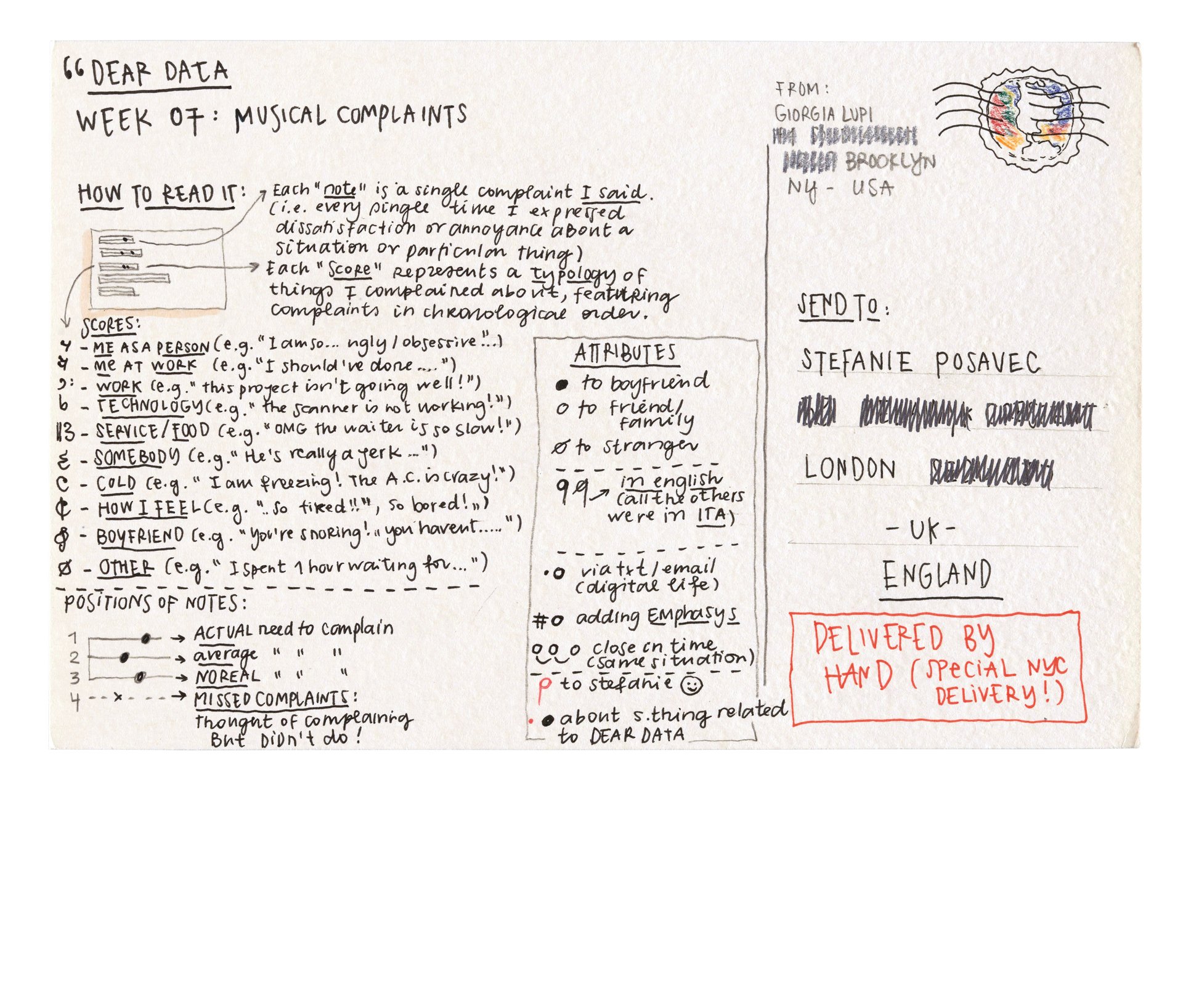

Lupi, cofounder and design director of information-design firm Accurat, drew a week of complaints with musical notation (with some liberties on what constitutes a note). A whole note on a bass clef meant a complaint to a friend or family member, in Italian.

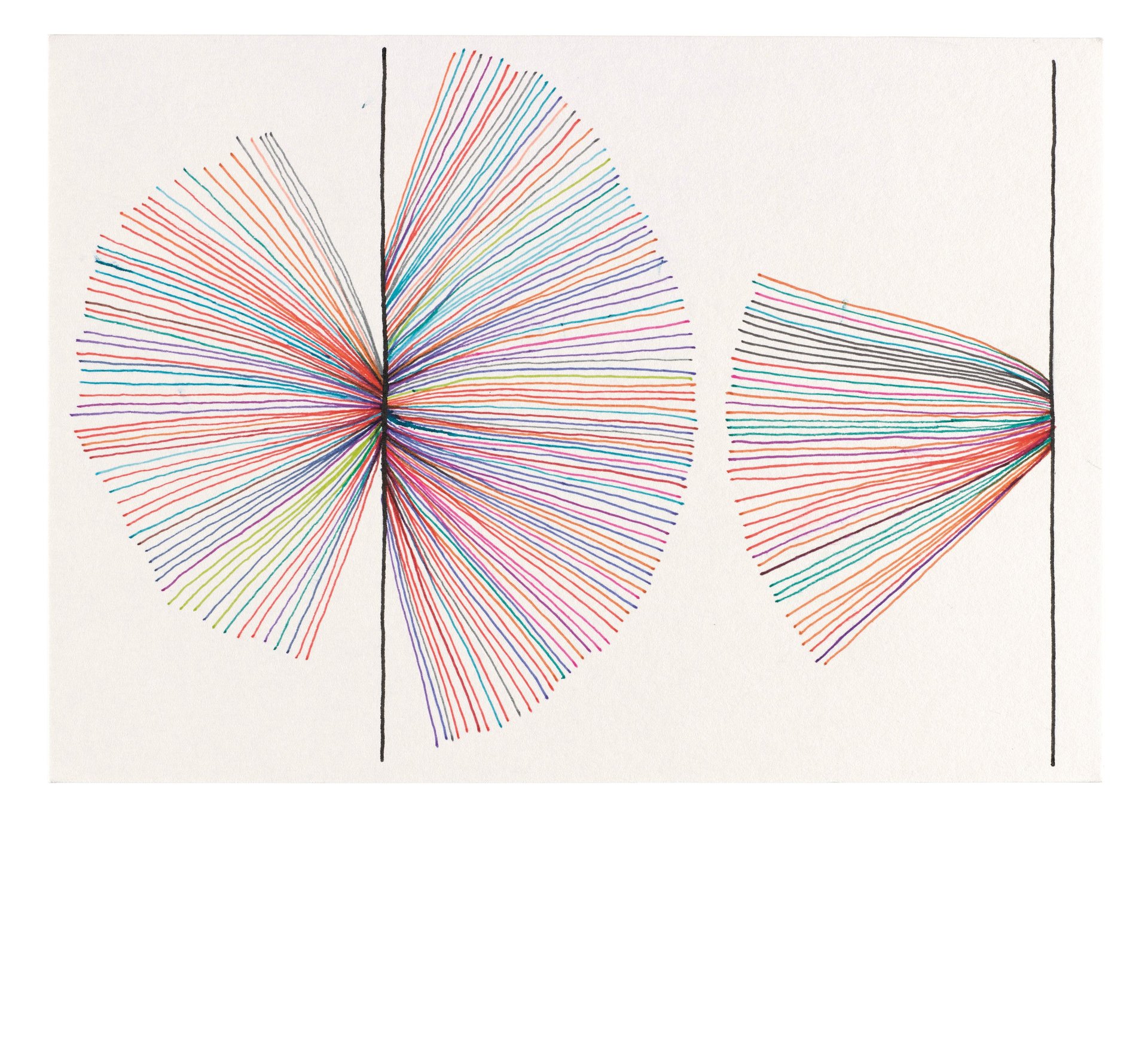

Posavec rendered her complaints as colored lines exploding from a vertical line, and chose to include other people’s complaints to her, not just her own. She also tracked her own private complaints, using blue lines for grumpiness about her husband, orange for gripes about society and the world today, and gray for dissatisfaction with her appearance.

People have taken the quantified self to some absurd lengths. But personal data collection and projects are no longer just for skilled designers; they’re for everybody, whether you like it or not. Sleep apps, fertility apps, apps that let you take a photo of yourself everyday, and monitor your calorie, caffeine, and alcohol intake have become a ubiquitous part of our lives, running beneath our apps, and frankly hard to turn off.

But while more and more that kind of tracking is automated, through devices like FitBit and the Apple Watch, Dear Data offers a more active approach to self-quantification. ”It’s a tool like journaling is, keeping track of your thoughts in a more qualitative way,” says Lupi.

Do it yourself

Start by asking, “What can I quantify or collect?”

Let’s say you want to know: How much sarcasm do I use?

Say the designers, start by asking sub-questions: Why am I sarcastic? For laughs, or to put others down? Who am I sarcastic to? Is it mostly in my head, or aloud? Where am I sarcastic? What times?

Then you gather the data, and spend some time with it. Find the meaningful arc in the information, and then start to sketch and doodle to find your own personal visual vocabulary.

Finally, draw the picture that shows that arc within the data. Draw a legend so the reader knows what you mean.

Lupi and Posavec’s approach teaches mental and emotional attentiveness. Their examples inspire you to think creatively about your personal habits, and to approach them with a slowness that lets you reflect on their meaning.

This meditation-meets-record-keeping makes perfect sense, as our accelerometers become one with our hands, wrists, and faces, even in our sleep. The things that are harder to track—our impatience, our jealousy, our fury, our forgiveness—there isn’t (yet) an app for that. But we can use emotional accounting as a tool to understand how we act, and why.