In this series, Perfect Company, we are examining pockets of excellence in the corporate world. No single company is perfect, but together they show what the corporate ideal could look like.

The platonic ideal

“Coming together is a beginning; keeping together is progress; working together is success.” —Henry Ford

The practice

In a lab in Dearborn, Michigan, Ford researchers, led by Mike Whitens and Ellen Lee, spend their days trying to determine whether the future of cars and trucks will be more like things grown in a lab than assembled on a factory floor.

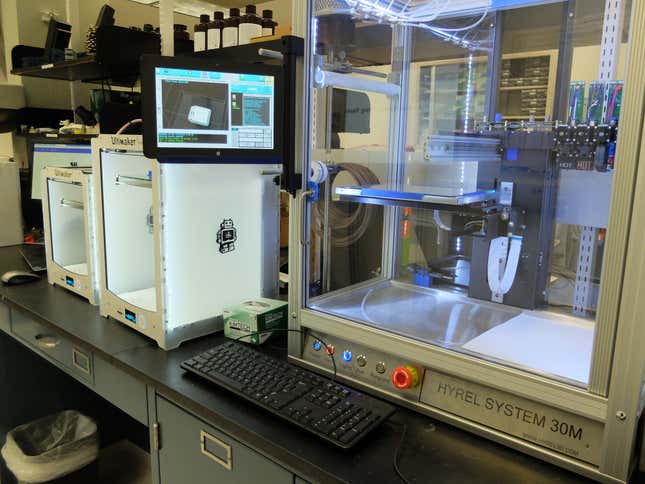

The group conducts experiments with just about every type of 3D printer on the market. It tests different grades of plastics, powders, and metals to see if they stand up to the rigors that Ford vehicles face over the years, whether they’re being used as taxis, police cars, commercial trucks, or just regular family cars. “We’ve been designing cars a certain way for a hundred years,” Whitens, Ford’s director of vehicle and enterprise science research said. “3D printing could change that.”

Ford has been using 3D printing to quickly create prototypes of parts for over three decades, Whitens said. In recent years, research from Ford and other companies has shown that 3D-printed materials could potentially be used in cars. Three-dimensional printing has the potential to upend the way that cars are produced. Instead of having to build complex machines and specialized tooling for each car part, theoretically, one machine could slowly builds the entire car up, layer by layer. As Whitens puts it, the team is asking, “What if we could grow parts out of a puddle of material?”

Ford has a long history of cutting edge research and development, dating back to its earliest days when founder Henry Ford ran the company. He spent years trying to make cars and other products out of renewable materials like soy, decades before any other manufacturer focused on renewables. And although the 113-year-old company has hit some rough patches in recent decades, its innovative spirit has once again pervaded the structure of the company, which CEO Mark Fields believes has set it up well for the next century. “We have innovation in our DNA —it goes back to our founder,” Ken Washington, Ford’s head of research and advanced engineering, says. The company may finally have figured out how to build at least part of a car out of soy, a century after Henry Ford tried to do it.

“Research is an insurance policy,” said Matt Zaluzec, a senior technical advisor working on making materials more lightweight, said of the work he and other researchers at Ford do. “Most of it is working on what they don’t know they need.”

The auto industry is once again undergoing sweeping changes with much of the attention focused on self-driving technology. Ford spent $6.7 billion on R&D last year, the same amount it spent in 2014, and up 8% from 2013. With so much at stake, Ford is methodical in how it goes about its research, which is split four categories. The first is fundamental research, to see if something could be done with a new material, manufacturing process, or technology. Then if the researchers’ theory holds up, it’s tested to determine whether it could really end up in a Ford production vehicle. Then that proof of concept is designed and built, and if it passes muster, it’s sent to production. There are many stages and milestones within each phase of research. Some things will not turn into products that Ford can develop, and some things will just plain fail. But as Henry Ford said, “The only real mistake is the one from which we learn nothing.”

It doesn’t matter if the research is something as fanciful as trying to grow parts from plastics and metals or as basic as trying out a new type of aluminum to make an F-150 a little lighter. This process is embedded in how every vehicle starts and finishes at Ford. Compare that with, say, General Motors, which has said that it’s only concentrating its research division on ideas that could quickly be implemented in cars and trucks.

Right now, the work of researchers in Debbie Mielewski’s renewable materials lab, which is currently trying to convert greenhouse gases in the air into useable products, like car seat filler is in the initial stages. Mielewski’s team has previously produced ideas that have made it through the entire gamut of research phases at Ford, such as proving that out-of-circulation paper currency could make the basis for a sturdy plastic that can be used in car interior items like—rather appropriately—the change holder. Her team is also working to keep Henry Ford’s soy dreams alive, having transformed soybeans into foam that now fills the seats in many US Ford models.

Ford recently shifted its self-driving car project into what the company calls the “advanced research project” stage, where a project moves from theory to practice. Fields recently said that Ford plans to have self-driving cars on the road in some capacity by 2021. On Sept. 12, Ford gave media a first glimpse at what riding in one of its self-driving cars will be like at an event in Dearborn. While many automakers and tech companies simply want to be the first on public roads with this technology, Ford doesn’t intend to put out a self-driving vehicle, in any capacity, until it believes it’s ready for consumers to use.

The takeaways

Ford is the only US automaker with a licensing arm for its intellectual property, and many of the projects its researchers work on find a life in things completely unrelated to cars. Mielewski’s team has helped bring cutting boards and other household items made out of plants to the market. They’re also working with Coca-Cola to produce the first soda bottle made entirely out of plant materials. Plastic bottles don’t need to be as durable as the parts in a Ford F-150 truck. “We don’t care where it ends up first,” Mielewski said.

And while Ford’s many research labs, such as the one in Dearborn (along with others in Palo Alto and Achen, Germany) may well be shaping the future of the company, they are not the only places where research is undertaken or encouraged. In 2012, the company worked with a Silicon Valley-area maker space called TechShop to open a lab that employees can join for a discounted rate. So an accountant with a passion for carpentry or a sales executive with a desire to learn about 3D printing can do so.

On top of that, anyone at Ford—from a first-year entry-level research assistant up to a managing director—can bring an idea to the company to get it patented. If a group of engineers, lawyers, and researchers think an idea is worth pursuing, the company will then help that person get the patent. But it’s not just patents, if Ford sees value in an idea, it will help that employee turn it into a reality. Employees are given a three-month subscription to TechShop, as well as money for classes, to try to prototype their idea. “We wanted to encourage them to actually build what was in their head,” Bill Coughlin, Ford’s president of global technologies business and member of the company’s general counsel, says. “That’s because an idea on paper is relatively easy to kill, so my thought was if we gave people the encouragement to be building their ideas, whether at TechShop or a Ford lab, that they could make a real difference.”

Coughlin said his initiative has tripled the number of inventions the company receives from across the company since the start of 2012. In 2015, Ford employees submitted 6,000 ideas for consideration to Coughlin’s team, up from about 4,000 the year before.

The company also started a series of “innovation challenges”—the first was an open call to design a futuristic e-bike in late 2013, which Coughlin said received over 100 ideas from around the company. The winning design came from someone whose day job is designing F-150 trucks, who was given a cash prize and the time and resources to turn his design into a product. The company is working on its second challenge—Ford wouldn’t offer specifics, but hinted it ties into the company’s urban mobility aspirations (think a Ford-branded Segway, perhaps). Coughlin said after the success of the first challenge, Ford’s received over 600 submissions this time around.

He added that he wants to encourage everyone at the company to be creative. “Because when people start thinking like inventors, it’s very hard to turn that off, and problems become opportunities.”