How Florida became the most important US state in the race to legalize self-driving cars

In 2012, Google dropped off two self-driving cars near the steps of Florida’s statehouse in Tallahassee. They were there at the behest of a freshly elected Florida state senator, Jeff Brandes. Lawmakers, some with families in tow, stepped into Google’s modified Toyota Priuses. With a Google employee standing by in the driver seat, the cars drove loops around the capital building, and then headed to the freeway, accelerating to 70 mph. No one touched the steering wheel for most of the ride, Brandes recounts.

In 2012, Google dropped off two self-driving cars near the steps of Florida’s statehouse in Tallahassee. They were there at the behest of a freshly elected Florida state senator, Jeff Brandes. Lawmakers, some with families in tow, stepped into Google’s modified Toyota Priuses. With a Google employee standing by in the driver seat, the cars drove loops around the capital building, and then headed to the freeway, accelerating to 70 mph. No one touched the steering wheel for most of the ride, Brandes recounts.

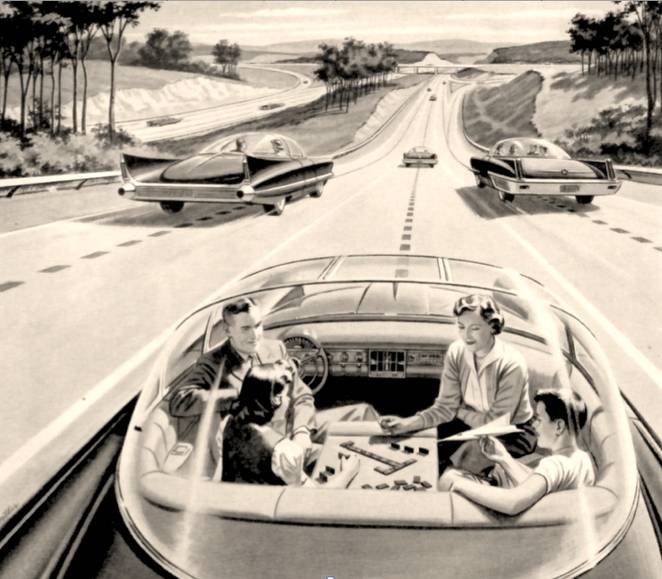

“It was an education campaign to get people to understand that this is the future,” Brandes told Quartz. “This is our generation’s transition from horse-and-buggy to the Model T.”

That day in Tallahassee led to a series of laws that has transformed the Sunshine State into the most welcoming place for autonomous vehicles in the country. On April 4, Brandes’ efforts culminated in the the passage of HB 7027, in a unanimous 118-0 vote, ushering in the nations’s first legislation to legalize fully autonomous vehicles on public roads without a driver behind the wheel. Florida is currently the only state that explicitly allows for true self-driving vehicles, says Adam Losey, a senior counsel at Foley and Lardner in Orlando. It puts Florida in position to shape legislation across the rest of the country.

“For the moment, Florida is the most important state as far as the legal aspects of autonomous vehicles go,” said John Terwilleger, a Florida business litigation attorney who has studied the state’s AV statutes. ”Frequently, the first state to pass legislation becomes the model for the remainder of the country, so it is very possible that Florida’s law will become a model.”

The legislative wheels are turning elsewhere. Last year, 16 states introduced legislation related to autonomous vehicles (AV), compared to just six in 2012, reports the National Council of State Legislators. Michigan, Nevada, and California are close behind Florida with their own AV legislation. On Monday (Sept 19), the US Department of Transportation (DOT) released guidelines that cleared away some of the uncertainty around safety standards. The non-binding guidelines leave plenty of room for future regulations, but recommend how driverless cars should respond to failures, protect user privacy, strengthen safety features, and standardize hardware and data protocols. Even cities are pushing ahead. Last week, Pittsburgh mayor Bill Peduto welcomed Uber’s public debut of autonomous vehicles, proclaiming that ”when it comes to innovation, regulation never comes first.”

For the AV industry, however, clear regulation would be a relief. But the flurry of competing legislation—ranging from Florida’s laissez-faire approach to California’s strict oversight—is causing worries. “Ideally, we’d like to see strong leadership from the federal government, not just to industry but to the states,” says Chan Lieu, a former National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHSTA) official and advisor to the Self-Driving Coalition for Safer Streets, which represents Uber, Lyft, Ford, Google, and Volvo. “We want there to be consistency across all 50 states, so autonomous vehicles don’t run afoul of laws crossing state boundaries.”

Today, car and technology companies are operating in a legal grey area. Traditionally, jurisdiction over motor safety was clear: the federal government regulates vehicles, and the states regulate drivers. That dividing line no longer exists. “It’s a new world where the vehicle is the driver,” a DOT spokesman told Quartz.

Consider the most basic issues: What exactly is an autonomous vehicle? Who is responsible when it crashes? Are they legal? Quartz asked lawyers around the country those questions. The only consistent answer was, “Nobody knows yet.” What’s certain is that self-driving car experiments are being run on roads where companies have pushed ahead of explicit regulation, or in places like Florida where regulators are welcoming them.

The race is on

Silicon Valley companies are famous for selectively ignoring regulations, and forcing lawmakers’ hands once public opinion tips in their favor. That strategy has succeeded for companies like Uber, Lyft and Airbnb, which dispatched loyal, voting customers against resistance from incumbent interests around the country. Autonomous vehicles, however, are blazing an opposite route.

States have competed with each other to legalize self-driving cars, and worked with companies to craft new legislation. Lawmakers tout AV-friendly credentials despite only preliminary testing, no federal safety standards, and at least one death when a Tesla Model S slammed into a tractor trailer in Florida while using ”Autopilot” software.

One factor, it seems, is economics. California and Nevada rely on the technology sector to provide jobs and money for their states. Google, Uber, and Tesla—all headquartered in California—are pushing hardest for autonomous vehicles. Michigan, too, wants to see Detroit and the entire US auto industry become more than just parts suppliers to Silicon Valley.

Then there’s Florida.

Florida has raced to become the leader on autonomous vehicle regulation since 2011, largely because of the benefits Brandes says the technology can bring to the state. One motivation, he says, is safety. Of the more than 33,000 motor vehicle deaths in the US each year, about 94% are due to human error. Almost all of them may be preventable with autonomous driving technology, say federal safety officials. The other is the once-in-a-lifetime chance to shape the transformation of American society. Autonomous vehicles promise to succeed where decades of mass-transit and highway construction have failed to slash traffic, cut fossil fuel use (pdf, p xiv), reconnect communities, and reduce the 20% or so of cities now devoted to parking. “I saw this affects the lives of all Floridans, and this was going to solve a lot of our problems,” said Brandes.

Brandes, who has chaired Florida’s transportation committee for four years, has managed to insert self-driving clauses in every transportation bill during his tenure. Every major city in the state must now include AVs in their long term planning, and a 14-mile major stretch of Tampa Bay highway near Brande’s home district is a federally designated testing lab for self driving cars.

His efforts culminated in the enactment of HB 7027 this summer. Although Florida first permitted AV testing in 2014, the newest law stripped out language around testing and the need for a driver to be physically present, according to the state legislature (pdf, p 4). Instead, the bill allows anyone with a valid driver license to operate an autonomous vehicle as long as the AV can alert operators of a technology failure. If the operator “does not, or is not able to” take control, then the vehicle must “be capable of bringing [itself] to a complete stop.”

In crafting the law, Brandes, said it was his intent to ensure the “operator” in this case does not have to be in the car (or even in the same state), monitoring the vehicle. He proposed a scenario where someone with a valid drivers license could open a smartphone app to summon a self-driving vehicle, and receive any alerts via the app. As long as the car could stop in the event of a problem, it would be legal. “It’s a possibility enabled by the law,” he said.

The caveat is that any autonomous vehicle under Florida’s law must meet the the US DoT’s definition levels of “Level 3” autonomy. No bright line delineates Level 3 cars yet except that they “enable the driver to cede full control of all safety-critical functions under certain traffic or environmental conditions,” and the driver “is expected to be available for occasional control, but with sufficiently comfortable transition time.” It also defers to federal law if the statute conflicts with national policy.

That leaves a lot of wiggle room. Car companies are just achieving Level 3 capabilities, although no cars are officially for sale yet. Audi plans to roll out Level 3 features in its A8 model by 2018, and has already tested self-driving prototypes in Florida (the state’s governor rode down a Tampa Bay expressway in one in 2014).

Tesla, which says its Autopilot function only meets the semi-autonomous Level 2 threshold, could theoretically qualify as Level 3 under some driving conditions, say some in the auto industry. In a January call with reporters, Tesla CEO Elon Musk said he thinks cars will be “autonomous within 24 to 36 months,” adding, “I’d be very surprised if it were beyond that point.”

Almost every major car company, and several technology companies, now plan to have AVs ready for the public before 2022. Google and Ford have both opted to jump straight to Level 4 to avoid the difficulties of the hand-off to humans in semi-autonomous vehicles. Google has said it plans to offer an automated vehicle by 2018, followed by Ford in 2021.

That’s outpaced even proponents’ expectations. “This was brand new for everyone in 2012,” said Brandes. “That’s still much faster than anyone is prepared for in government.”

Rather than take action, a few states have noted their existing motor vehicle codes do not expressly prohibit operation of self‑driving cars. “A lot of states haven’t even addressed AV,” said Michael Reynolds, a lawyer with O’Melveny & Myers in LA. ”People look at that and say, ‘Well, if they don’t explicitly prohibit it then it’s not illegal,” Reynolds said.

Those states, he argues, may even have more opportunities for deploying AV, although how to apply laws requiring a drivers licenses, seat belts, and hands on the steering wheel in vehicles without a human driver would be up to a judge.”It’s hard to say what would happen,” said Reynolds.

“Considerable legal uncertainty”

The US government has now cut through some of the chaos.The DoT’s more unified national framework includes a 15-point safety design standard for AVs, as well as a call for states to harmonize their policies. It also indicated the government was ready to recall any vehicles it found unsafe.

For now, the DoT is taking it slow. “We left some areas intentionally vague because we wanted to outline the areas that need to be addressed and leave the rest to innovators,” Bryan Thomas, a spokesman for the Department of Transportation, told The New York Times on Sept 19. Ultimately, however, the federal government believes autonomous vehicles “will save time, money and lives.”

Perhaps the most pressing question to answer is: Who is responsible if there’s a crash? ”That’s something that’s been left up in the air with autonomous vehicles,” said Reynolds. It has proven to be perhaps the most worrying issue for automobile industry executives. In interviews with industry stakeholders in 2013, the RAND Corporation found liability outweighed almost any other concern. One manufacturer claimed that “we will never make a car that doesn’t have a driver,” according to RAND (pdf, p 152)

Courts will likely be forced to decide the issue soon, say legal experts. States, so far, have been happy to leave liability up to the courts. “The question that comes up is: Who do you license?” said Brandes. “Do you license the driver? License the car? License the software? I’m in the camp that you license no one.” Instead, Brandes says, an autonomous vehicle is a product, and should be administered as one in the case of an accident. Brandes says he crafted Florida’s law so that courts could apportion liability under existing laws.

That may actually work, says Bryant Walker Smith, a law professor at the University of South Carolina. Florida’s law does a “pretty good job” of laying the legislative tracks for future AV, wrote Smith by email. “The law does leave considerable legal uncertainty,” he wrote. “But this is inevitable, and limited deployments will soon provide a more concrete way to approach these issues.”

A second approach would be to replace today’s “fault” system with a common insurance pool for all companies. That mirrors what Congress created to cover vaccines, aircraft, and nuclear energy in order to shield industry from litigation. A law could remove AV manufacturers’ liability for accidents to encourage investment and innovation, but compensate victims out a common fund, suggests RAND (pdf, p 131). The devil is in the details: Congress would need to find a way to defend against defective products, while avoiding litigation against the dozens of companies that have a hand manufacturing automated vehicles. If courts find they cannot fairly assign blame in accidents in which the drivers are a fusion of software and hardware, there may be little other choice.

For now, governments are walking a line between public safety, and stifling a technology with huge potential benefits for society.