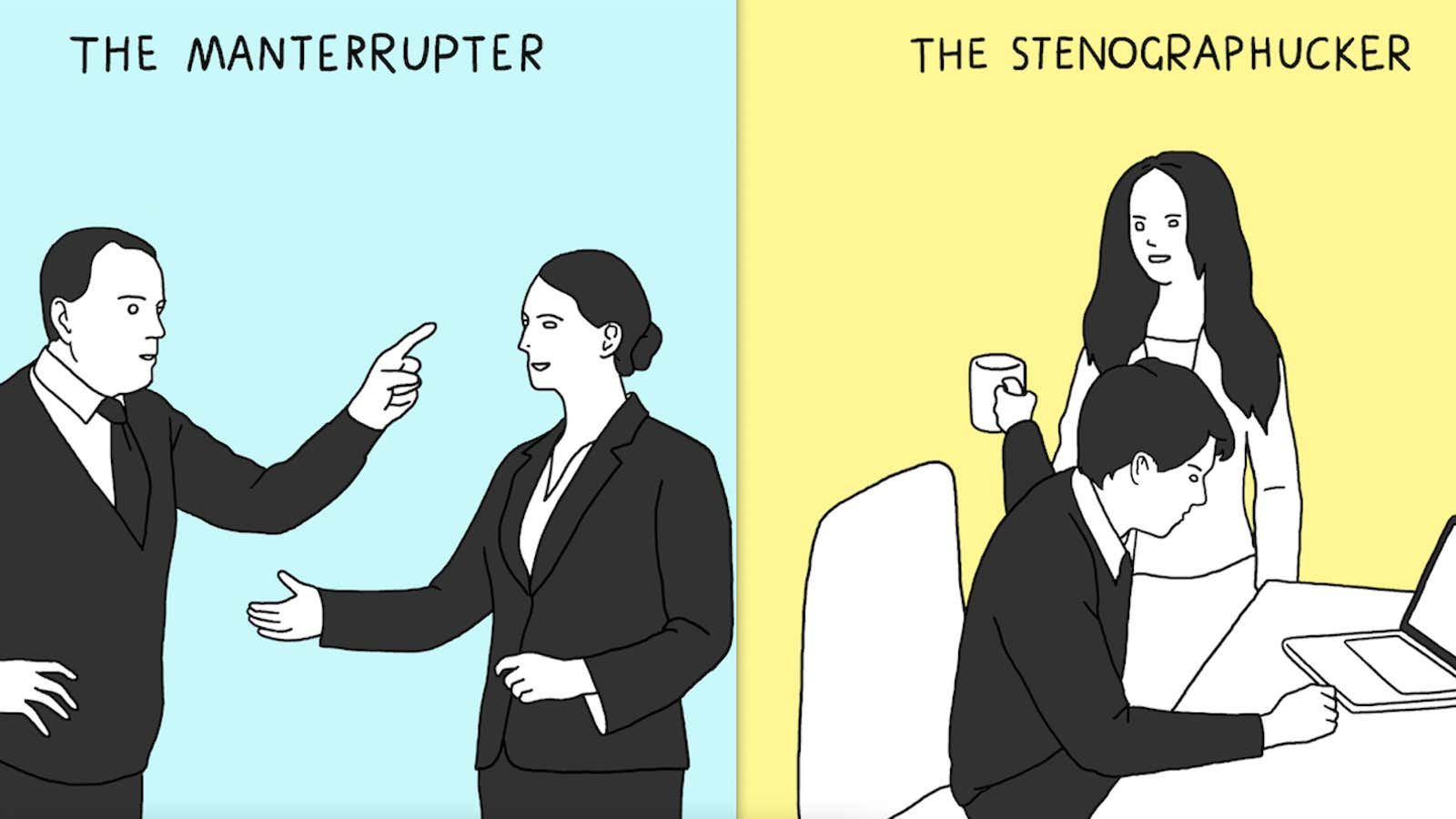

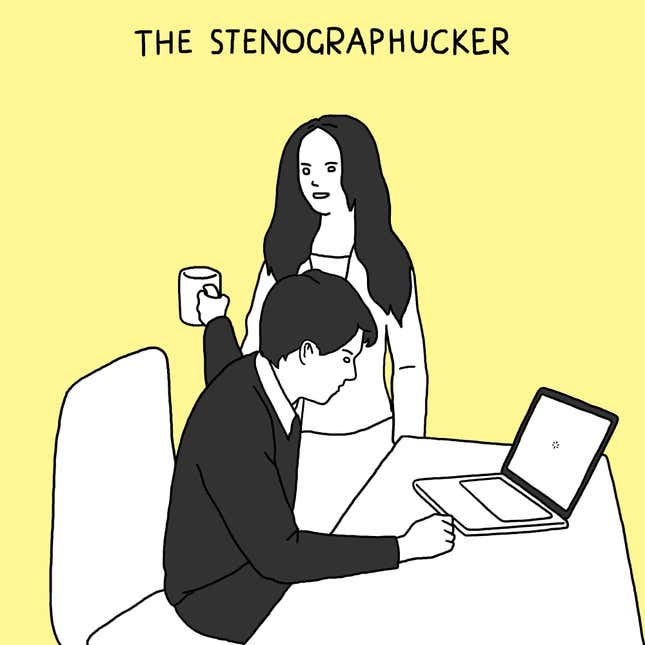

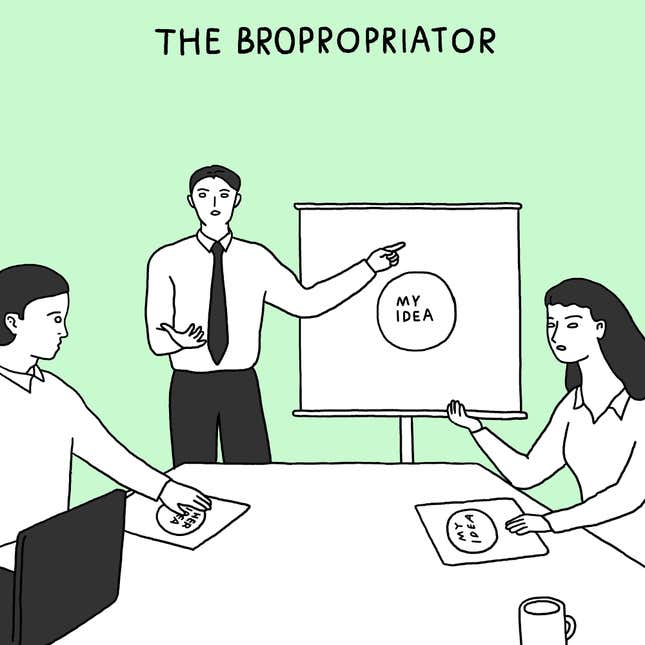

Jessica Bennett’s new book Feminist Fight Club: An Office Survival Manual (For a Sexist Workplace) is an irreverent yet academically-grounded look at the many different ways that women continue to confront sexism in the workplace. The following excerpt is from a section all about “knowing your enemy” and knowing how to fight it. (All illustrations courtesy of Fanqiao Wang.)

The Enemy

The Stenographucker treats you like the office secretary, even when it’s clear you’re not: asking casually if you’d “mind taking notes,” ccing you on his travel arrangements, or ordering you to “grab coffee” for a client (your client). Sometimes he inadvertently assumes you are the secretary (or the kitchen help, in the case of Mellody Hobson, the black female chair of the board at DreamWorks). My friend Alia, who works at a nonprofit, recently attended a cocktail reception for a prestigious scholarship she’d won. Along with the other honoree, a man, she was asked to greet guests at the door. But instead of outstretched hands to congratulate her—those went to the man by her side—she received more than a few coats in her face. People assumed she was the coat-check girl.

The Fight Moves

Bad Barista

Do what digital strategist Aminatou Sow does: when male colleagues ask her to make coffee, she tells them politely that she would be happy to do so, if only she knew how—her mother told her never to learn how to make coffee so she wouldn’t end up having to make it. (The copy-machine equivalent: “I’ve broken the copy machine so many times, I’m not supposed to touch it.”) For further inspiration: see Shel Silverstein’s “How Not to Have to Dry the Dishes,” which every woman might consider having tattooed to her arm (“If you have to dry the dishes / And you drop one on the floor— / Maybe they won’t let you / Dry the dishes anymore.”)

Cash In Your Woman Card

Katharine O’Brien, an organizational psychologist, says she uses the following strategy to avoid being disproportionally asked to help out: she says no, and then explains bluntly that she doesn’t take meeting notes because she believes it puts women in a subordinate position—of having to record, not speak. “I’ve done this for years and I’ve found it to be very effective,” she says. “Most people understand my reasoning and any contention it causes has been fleeting.”

Throw to a Bro

That is, backhand this assignment by suggesting another guy for the job. “I’m actually on the hook for a big presentation right now. But you know who’s actually great at making spreadsheets? Brad over here. Brad is excellent at making spreadsheets.” Other possible comebacks include “Would you like me to get you coffee while I’m at it?” and “Are your hands broken?”

Put the Phucker in His Place

I once heard a story of a female CEO who was chastised by a colleague for being out of Diet Coke in a board meeting that she was chairing. Instead of getting upset, she turned to the man and said sweetly, “I’ll be sure to add that to the agenda for next time.” He shut up.

No Volunteers Allowed

Research shows unequivocally that the majority of secretarial tasks fall to women, but women are also more likely to say yes to doing them—and to volunteer of their own accord. We know, saying no can be difficult. But here’s one thing that’s not: not offering in the first place.

The Enemy

You could argue that our country was founded on a bropropriation of sorts: a white man (Columbus) and his crew (more white dudes) claiming credit for discovering a New World that wasn’t actually new (or theirs). In an office setting, the Bropropriator appropriates credit for another’s work: presenting the ideas of his team as his own, accepting credit for an idea that wasn’t his, or sometimes even doing nothing at all and still ending up with credit—a convenient reality of being born male, where credit is assumed. When it comes to women in particular, bropropriation is backed up by fact: women are less likely to have their ideas correctly attributed to them, and we have a centuries-long history to prove it.

The Fight Moves

Tough Talk

It’s pretty hard for someone to take credit for your idea if you deliver it with such authority that nobody can forget it. So speak up—no ums, sorrys, or baby voice allowed. Use active, authoritative words that show you’re taking ownership of what you’re saying. Not “I wonder what would happen if we tried…” but “I’d suggest we try…”

Thank ’n’ Yank

Yank the credit right back—by thanking them for liking your idea. It’s a sneaky yet highly effective self-crediting maneuver that still leaves you looking good. Try any version of: “Thanks for picking up on my idea.” “Yes! That’s exactly the point I was making.” “Exactly. So glad you agree—now let’s talk about next steps.” Sure, sometimes a biting “Is there an echo in here?” may also work, but the thank-n-yank softens the edge.

Wingman

Find a buddy—and maybe even a buddy who is a dude. Ask him to nod and look interested when you speak. Let him back you up publicly in meetings. Have him affirm what you say. When somebody tries to take credit for your (or others’) work, watch as he speaks up: “Yeah, like Jess said.” He corrects the problem, gets applauded for it, and you don’t have to say a word.

E-vidence

Keep an email evidence dossier. If you’ve put forth an incredible idea in public, follow up with an email to your higher-ups summarizing your idea after the meeting—and cc whomever necessary to let them know it’s on the record.

Snaps

If you hear an idea you like from a woman, support her publicly. Nod; say “yes!”; clap your hands; or even snap your fingers. It’s the IRL equivalent of a Facebook “like.”

The Enemy

A quick pop culture history refresher: remember that moment back in 2009, when Kanye West lunged onto the stage at the VMAs, grabbed the microphone out of Taylor Swift’s hand, and launched into a monologue? “Imma let you finish,” he said, as Swift stood by in stunned silence. “But Beyoncé had one of the best videos of all time!”

Whether or not you agreed with his musical assessment (or the fact that he had appointed himself spokesman for another powerful woman) it was the most publicly memorable instance of a manterruption—a man interrupting a woman while she was trying to speak (in this case, on a stage, alone, trying to accept the award for best female video). But to a certain breed of working woman, Kanye’s behavior was familiar. We speak up in a meeting, only to hear a man’s voice boom over ours. We chime in with an idea, perhaps a tad too uncertainly—and a dude interjects with authority. We may have the ideas, but he has the vocal cords—causing us to clam up, lose our confidence, or cede credit for our work.

Studies show the Manterrupter is real: men speak more than women in professional meetings, they interrupt more frequently, and women are twice as likely as men to be interrupted by both men and women when they speak (and even more if they’re a woman of color). It’s not just Taylor who gets shafted.

The Fight Moves

Verbal Chicken

This is the verbal equivalent of two cars racing toward each other at top speed until one (his) swerves. Your job is to stay strong and just keep talking. Keep your pauses short. Maintain your momentum. No matter if he waves his hands, raises his voice, or squirms in his chair, do you. Pretend to be deaf if you have to; it’s worth it if it helps you make your point. The key is to prevent him from getting a word in while simultaneously acting like you are the chillest person in the room. That, and a side-eye that says, “DON’T YOU DARE FUCKING INTERRUPT ME.”

Womanterruption

Sure, you can call out a Manterrupter: “Bob, I wasn’t done finishing that point. Give me one more sec.” But imagine for a second if Beyoncé had walked up onstage where Kanye was busy interrupting Taylor and interrupted him. This is what we call womanterruption, or interrupting a Manterrupter on behalf of your fellow woman. If you hear an idea from another woman that you think is good, back her up: “Wait, can you let her finish?” If you can tell a woman can’t get a word in, interject and ask a question: “Nell, what is your opinion?” You’ll have more of an effect than you might think—and you’ll establish yourself as a team player.

Lean In (Literally)

In one study, researchers found that men physically lean in more than women during seated meetings, making them less likely to be interrupted. (Lyndon B. Johnson was famous for his lean.) Other methods of asserting your physical space when you have something important to say: Sitting at the table instead of in the back of the room, pointing to someone, standing up, placing your hand on the table, or making eye contact. Bonus tip: men often arrive at meetings early in order to get a good seat. It’s not a bad idea in general to place yourself in the closest physical proximity to where the important conversations are being held or decisions are being made.

Kanye-Free Zone

If you’re in a position of power: establish a no Kanye-ing rule. People do not interrupt—as policy—while people are speaking or pitching, and those who try to grab the mic will be shamed. If you must, employ that elementary school tool of the talking stick. You may laugh, but the manager of a seven-hundred-person team at Google says she employs this method.