Having grown up in Asia, I didn’t go to Washington, DC’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) expecting to find myself represented in its galleries.

And yet there I was. Childhood memories flooded back when I spotted Janet Jackson’s masterful 30-year-old first album, Control in an interactive exhibit. My dad’s tennis idol, Arthur Ashe, had a display case. A picture of the inventor of Aunt Jemima pancake mix reminded me of how my mom in the Philippines would make flapjacks with slices of cheddar cheese dropped in the batter. And a wall of commemorative buttons from president Barack Obama’s inauguration brought me back to that euphoric day, when massive crowds flush with optimism flocked to the National Mall in Washington, DC, where I was a grad student.

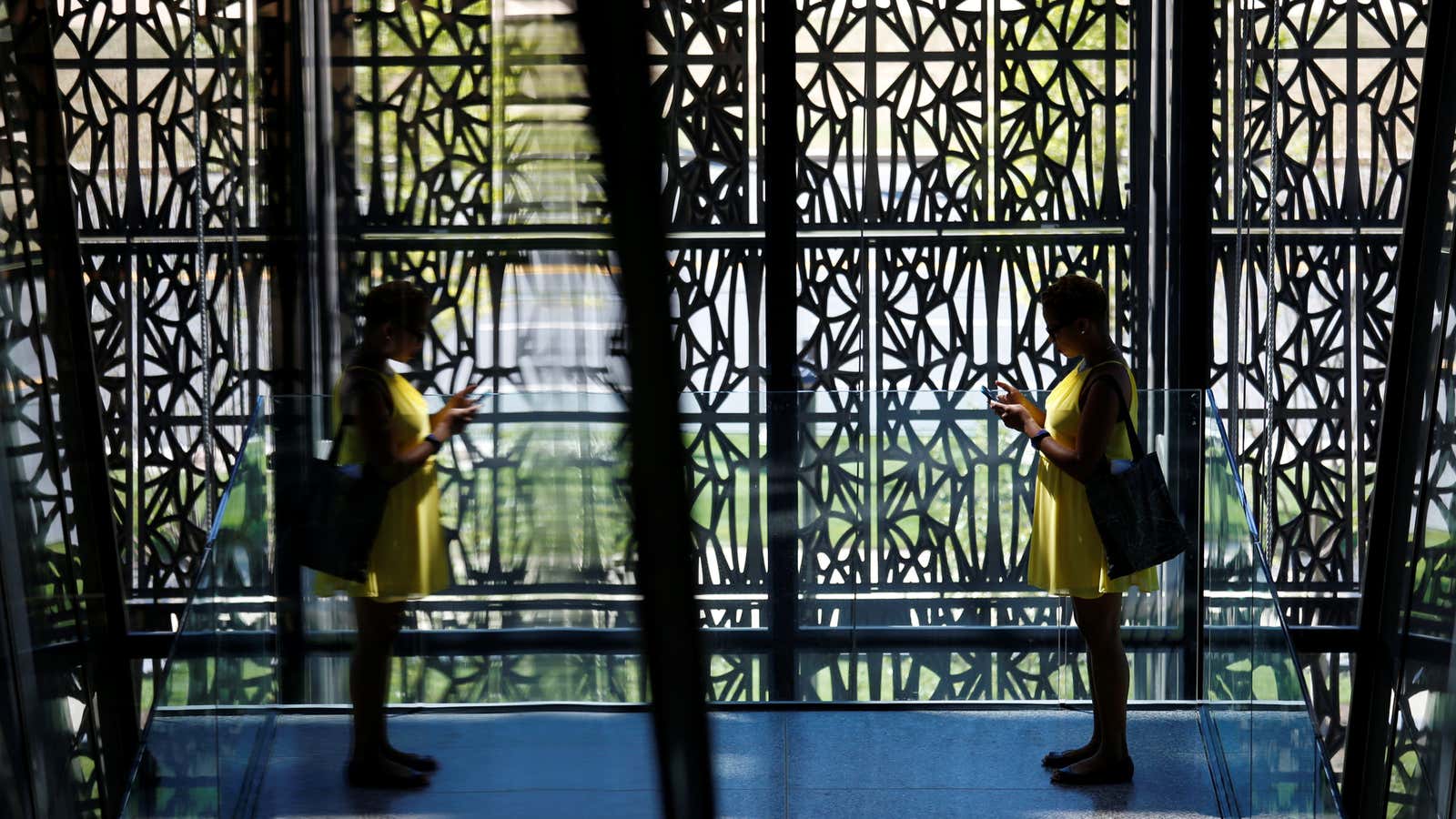

That mall is where the astonishing Smithsonian museum now stands. Thirteen years in the making—or a century if you count back to the 1916 congressional bill proposing “a monument or memorial to the memory of the negro soldiers and sailors”—the museum (which opens to the public today, Sept 24), is a staggering reminder of how much American black culture has influenced how the whole world dresses, eats, sings, speaks, and works. I left the museum feeling connected and schooled about the United States, and also about my own upbringing on the other side of the globe.

As a national museum, the Smithsonian needed to appease many interests and recognize many under-represented groups. The building was meant to be more then just a museum—also a monument to African American history, community and culture. Big name architects such as Moshe Safdie, I.M. Pei, and Norman Foster competed for the coveted $540 million government commission, partly funded by private donations from the likes of Oprah Winfrey, Bill Gates, and Michael Jordan, as well as finance world titans Robert Frederick Smith and David Rubenstein.

The lead designer chosen for the project, the British Ghanaian architect David Adjaye, said he got the job by keeping those three aspects of the project in mind—history, community, and culture. “We were the only team who acknowledged the tripartite structure,” Adjaye told me, as workers nearby rushed to make last minute adjustments for the museum’s grand opening.

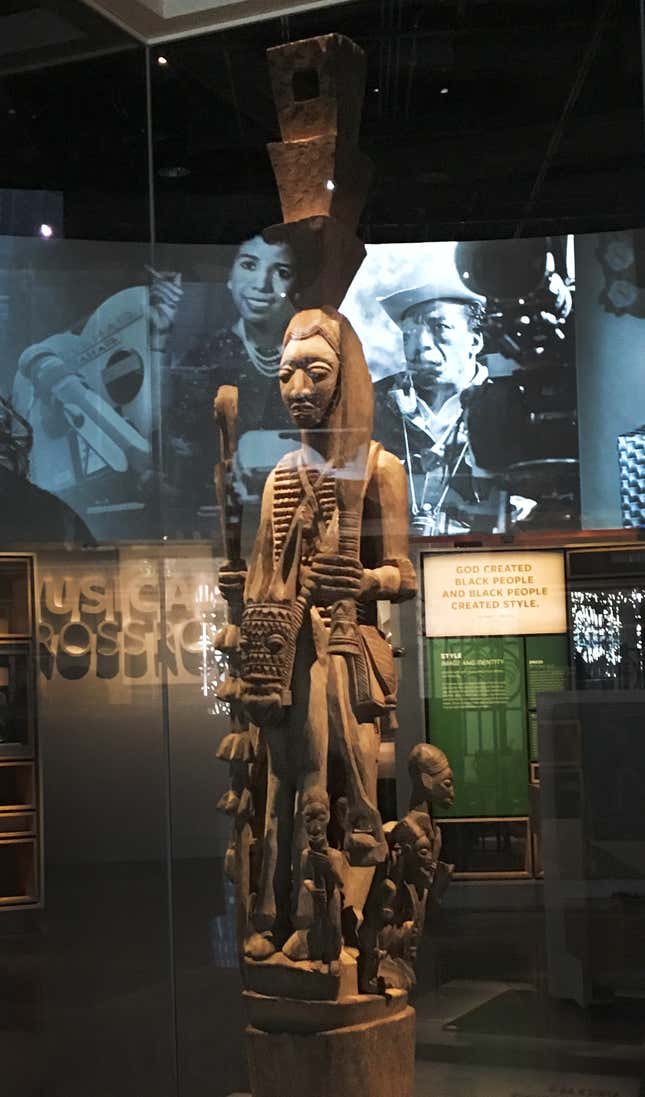

The sought-after 49-year-old architect’s concept came from his research into the beginnings of slavery in Central and West Africa, which led him to study Yoruban culture. A three-tier crown from a carved wood sculpture by the Nigerian artist Olowe of Ise gave the museum its central design metaphor.

The museum relies on the building’s tripartite architecture to organize 37,000 objects—photographs, hair combs, hats, sneakers, Chuck Berry’s Cadillac, fragments of an 18th-century slave ship—that it has been accumulating since the US Congress approved the museum’s construction in 2003.

The vastness of the museum’s collection has bothered some critics. The hundreds of artifacts, display objects and media displays spread across the 400,000 sq. ft. museum are overwhelming. It’s hard to piece together the single story of the NMAAHC.

But the museum’s lack of a singular, dominant polemic is also a strength. This curatorial mish-mash—or episodic cacophony—gives visitors a way to dip into the subject and find aspects that interest them.

Indeed, walking through the museum feels like flipping through TV channels, with hundreds of tantalizing showcases vying for attention. Adjaye says that the best way to experience the museum is to start at the basement. He advises visitors to descend down the Richard Serra-esque staircase to the dramatically-staged galleries portraying the origins of slavery, and then climb up through the upper levels to ultimately view a display about president Obama. The progression from the museum’s dark subterranean chambers to the bright, joyful galleries on the top floors evokes the African American’s “journey into the light,” he explained.

“That’s the emotional power of architecture, to bring you into a journey and to give you uplift,” Adjaye said. “The greatest cathedrals, temples and shrines give you uplift, and I think architecture is best when it supports the narrative through the articulation of space.”

But the museum works backwards too. During a pre-opening media event, reporters who weren’t able to get a seat inside the Oprah Winfrey auditorium for the museum director’s remarks were herded to the upper galleries, which are dedicated to black artists’ influence on pop culture.

At that top level, an absorbing—if overstuffed—hall of fame showcased African American musicians from Sam Cooke to Nina Simone, P-Funk to Slick Rick, Eazy-E to MC Hammer—honoring generations of childhood idols f0r people all over the world. Music fans could easily while away an entire afternoon flipping through records at an interactive installation where one can instantly cue any number of albums from the touchscreen table. (That’s where I found that Janet Jackson record sleeve.)

On the third floor, an homage to African American sports heroes begins with a sensational mural of track and field superstar Florence “Flo-Jo” Griffith Joyner. Wandering through the narrow corridor reminds us of how many black athletes we’ve lionized, from football stars and basketball players to Olympians—and of course my dad’s favorite, Arthur Ashe. Life-size bronze sculptures in the gallery double as secular altars and impromptu photo-op zones. In front of a rather imprecise likeness of Venus and Serena Williams, visitors queued to take a selfie between the sibling tennis idols.

Another visitor reverently makes the black power salute next to a sculpture of Olympians Tommie Smith and John Carlos, a tribute to their silent protest on the 1968 Olympic medal stands.

On the same floor, a succession of historical vignettes follow. Not to be missed is the recreation of the 1940’s meeting room where the National Council of Negro Women convened, accurate down to the embroidered NCNW monogram, the crimson carpet, and a bookshelf of pamphlets from the era. Sitting in one of the wooden armchairs felt like being part of Mary McLeod Bethune‘s circle of 28 leaders discussing pressing issues affecting American black women in the Jim Crow era.

On a smaller, though no less special scale, a bookcase of family portraits and head shots serves as an homage to the South Carolina photographer Henry Clay Anderson, who ran a famous photo studio and captured “the dignity, integrity and depth” of black people for 30 years. Anderson, whose vernacular art has been largely ignored by major museums, finally finds a place of honor here.

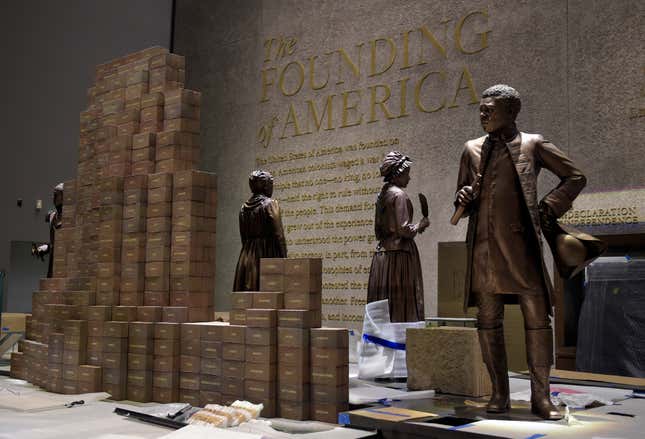

Descending to the bowels of the building (the media research library and gallery space on the second level were closed when I visited), a monumental film projection flickers past the small gallery doors to introduce the historical section of the museum. Here the designers play with scale, lighting and props—pulling out all the stops to dramatize the grim aspects of African American history, beginning with the trans-Atlantic slave trade in the 15th century.

Many of the museum’s most precious artifacts are displayed in this underground vault. Among them are garments owned by Harriet Tubman and Rosa Parks, a bible owned by slave rebellion leader Nat Turner, and a pair of hand cuffs sized for an enslaved child. A Southern Railway segregated train car is dramatically installed in the middle of a hall.

Through its tour-de-force exhibitions, NMAAHC—the largest African American museum in the US, eclipsing the Charles H. Wright museum in Detroit—gets several attempts to capture, educate, move, and represent visitors from the US and all over the world.

The staggering succession of well-visualized displays, amped by the best tricks of museum exhibit design, deliver an emotional punch. And in an age of short attention spans and social-media-fueled distraction, getting someone’s attention is impressive in itself.

The building’s architect of record, Phil Freelon, advises visitors to pace themselves and plan several visits to the museum, like one would take in big museum complexes like New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Louvre in Paris. “Don’t come to the museum and expect to take everything in within a couple of hours,” he said.

Among the most important architects in the US today, Freelon says this particular project is personal. “As African American man in the US, it’s an incredible honor to work on this,” he said. After nine years on the project, Freelon says, he feels a sense of accomplishment and relief: “It’s been a long journey, and I look forward to visiting this museum when I’m off duty.”

Like Freelon, the 46 million African Americans in the US today have been longing for this monument to their history and cultural influence. For some, the museum is a reckoning, for others, a celebration.

Entry to the NMAAHC is free but pre-booked tickets are gone through November. To accommodate large crowds, the museum plans to extend its operating hours for its opening weekends. Those who loathe planning ahead and have time to queue can take their chances for same-day passes starting on Sept. 26.