This is what happens when we build walls and fences to keep people out

It’s been over a year since Donald Trump announced his US presidential run in a speech that promised to build an “impenetrable, physical, tall, powerful, beautiful, southern border wall” along the US-Mexico border. At the same time, Europe was confronted with its worst refugee crisis since World War II.

It’s been over a year since Donald Trump announced his US presidential run in a speech that promised to build an “impenetrable, physical, tall, powerful, beautiful, southern border wall” along the US-Mexico border. At the same time, Europe was confronted with its worst refugee crisis since World War II.

Over a million migrants fled to Europe by sea in 2015. European leaders were unable to agree on a united approach as the crisis unfolded on their doorstep—and many took the Trumpian approach.

In 2015 alone, Hungary, Austria, Slovenia, Macedonia, and Bulgaria all started construction or announced plans to build fences. In the last two months, Norway has begun construction of a steel fence at a remote Arctic border post with Russia to deter migration. France, with British funding, is the latest to build its own wall—near the so-called makeshift refugee camp known as the Jungle. It has been dubbed the “Great Wall of Calais.”

Building fences in Europe isn’t anything new, as Berliners know all too well. What’s remarkable is the pace these fences are going up.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, European countries have built or started 1,200 km (750 miles) of anti-migrant fences, costing at least €500 million ($570 million). Most of the construction started in 2015, according to a Reuters analysis. At least seven new border walls have been built since the start of last year.

“Fences and walls are nothing more than expensive screens we use to try to conceal our problems from view,” Zoe Gardner, a spokesperson for Asylum Aid, tells Quartz. “Certainly, they may make it harder or more difficult for men women and children to reach safety and a place where they can build a new life, but they cannot remove the hope that motivates their journeys and they will not stop people from trying.”

A growing number of human-rights groups warn that fences have failed to reduce migration as migrants are instead forced to take a more dangerous routes to Europe. This is why the Calais wall will ultimately fail, Gardner says. “They have endured and triumphed over war, torture, poverty and long, dangerous journeys to get here. Having crossed the Sahara, it will not be our wall that stops them.”

What these fences often do is simply divert migrants from one border to another. Take Europe’s current dilemma, which can be traced back to events that took more than a decade ago.

From land…

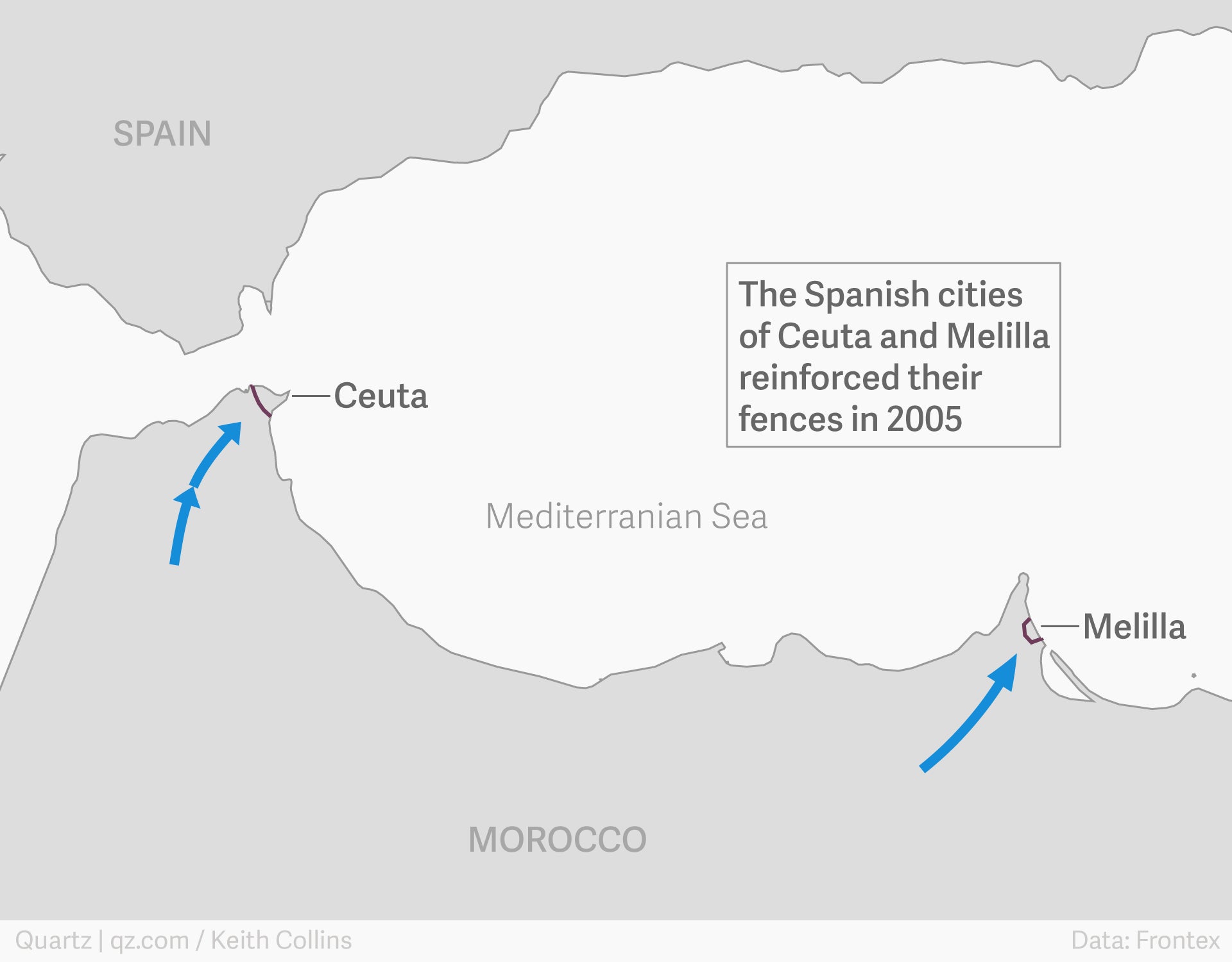

The only land border between Europe and Africa, where Spain and Morocco meet, was thrust into the spotlight in 2005, when 11,000 Africans tried to get over the fences to reach the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in the first nine months. This would come to be known as the Western Mediterranean route. Spain responded by building more fences, and reinforcing the ones it already had to deter migrants, spending more than €30 million.

With the Spanish enclaves significantly more difficult to breach, there was a slight shift of the migratory route from Ceuta and Melilla to the Canary Islands, known as the Western African route, according to a recent report (pdf) by Amnesty International. Spain then increased border controls at the Canary Islands.

As Spain ramped up controls and reinforced fences in one border, migrants would shift to another, creating a cat-and-mouse game between the borders at the Spanish enclaves and Canary Islands, until eventually, Spain was able to effectively close off both these routes.

So migrants began taking a very indirect route known as the Eastern Mediterranean route as a result of the heavily fortified borders at the Spanish enclaves and Canary Islands. Frontex, the EU’s border protection agency, described the land border between Greece and Turkey (pdf) as the ”unquestionable current hotspot for illegal border-crossing into the EU” in 2010.

As a result of the large number of migrants traveling through its land border with Turkey, Greece constructed a fence alongside its border with Turkey in December 2012. With the Greece-Turkey land border closed off, detections of illegal border-crossing at the Greek land border with Turkey fell dramatically.

The fence resulted in an immediate displacement from the Turkish-Greek border to the border between Bulgaria and Turkey. The numbers of migrants apprehended at Bulgaria’s border with Turkey increased from 1,700 in 2012 to 11,158 the following year (pdf), according to Amnesty International.

To stem the flow of migrants crossing its border with Turkey, Bulgaria started the construction of a 30-km fence in the border area between the villages of Lesovo and Kraynovo. The number of migrants entering Bulgaria over the Turkish border dropped from 8,000 between September and November 2013 to just 302 between 1 January and 26 March 2014, Amnesty International notes.

…to sea

Efforts to reduce migration by building fences and increasing border controls have had mixed results, according to the Migration Policy Institute:

Rather than deterring migration altogether, early evidence suggests increased enforcement of land borders has frequently served to increase maritime migration, with flows adapting to changing enforcement conditions. Maritime migration is both more dangerous for those migrating—who frequently turn to smugglers for assistance—and more difficult for policymakers and authorities to manage.

The number of migrants apprehended on Greek islands or in the Aegean Sea rose from 169 in 2012 to 3,265 (pdf) in 2013, according to the Greek police. By 2015, the number of migrants detected crossing the sea crossing rose to 873,179, according to Frontex (pdf), becoming the most popular route to enter the EU.

Once migrants arrived on the Greek islands, many used the Western Balkan route to reach Western Europe in 2015. The Hungarian government claimed that 160,000 people had already arrived into the country irregularly in 2015. Hungary went on to build a fence alongside its Serbian border in September 2015, which is estimated to have cost around €98 million (pdf).

Hungary was, at the time, widely criticized for constructing the fence, but as the crisis unfolded, other countries quickly followed suit. After building the fence, Hungary reported a sharp decrease in the number of migrants at its Serbian border—by Oct. 6, 2015, Hungarian police reported that only 11 (pdf) had entered the country irregularly from Serbia.

Pleased with the dramatic drop in migrants entering the country, Hungary went on to build another fence alongside its border with Croatia in October 2015.

Slovenia then built a fence alongside its border with Croatia in November 2015 and Macedonia finished constructing a fence along the border with Greece the same month, which left more than 50,000 people stranded in Greece. By the end of 2015, Austria followed its neighbors and constructed a fence near the town of Spielfeld at the Slovenian border, which it completed in January 2016.

With the Balkan route to Western Europe effectively closed, Frontex noticed a new, more dangerous route opening up: the so-called Arctic route.

Migrants usually crossed from Storskog, the only legal land border crossing between Norway and Russia. Around 6,000 migrants were detected between October and December 2015, according to Frontex. The vast majority originated from Afghanistan and Syria. Norway responding by constructing a fence along its Arctic border with Russia.

One of the few routes left for migrants is from Libya to Italy or Malta, known as the Central Mediterranean route. With the devastating civil war in Libya, and restrictive fences and border patrols at the West Mediterranean route, more migrants opted for the Central Mediterranean route instead, as they believe they are less likely to be returned if detected by authorities.

This route has been described as one of the most dangerous route to Europe, with almost 3,000 dying last year. Already at the start of this month, in just two days, the Italian coastguard rescued more than 10,000 migrants on rickety boats in the Mediterranean.

The EU’s new Border and Coast Guard Agency, the successor to Frontex (paywall), has its work cut out before it’s even up and running.