After Virginia governor Terry McAuliffe, a Democrat, decided to grant voting rights to 200,000 former felons in April, he was quickly accused by his Republican opponents of ushering in new voters for Hillary Clinton. Because Virginia is a battleground state for the November elections, and some US contests have been decided by margins smaller than 200,000, the fight between McAuliffe and GOP lawmakers has once again raised the question: Should convicted felons get to vote?

The United States is unique in how it handles voting rights for people convicted of a crime. The Fourteenth Amendment allows each state to make its own rules when it comes to granting them the right to vote. In some states, ex-offenders are essentially barred from voting for life. Only two states let prisoners vote. According to research conducted this year by the Sentencing Project, about 2.5% of the adult US population, 6.1 million voters, are disenfranchised because of a felony conviction. Because the US disproportionately convicts people of color, this sort of disenfranchisement can have crucial political and social consequences.

The United States and its racist history of felony disenfranchisement

Only a handful of European countries ban people in prison from voting, and those include Bulgaria, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary and Russia. In others, either all inmates are allowed to cast their ballots, or it depends on the gravity of their crime. In the UK, there’s been a long debate over granting prisoners the right to vote, with former prime minister David Cameron famously saying it would make him “physically ill” to do so. Prisoners can’t vote in Brazil, Argentina or India, but they can in Canada, Israel or South Africa. But these countries do not take away voting rights from those who have already paid their debt to society.

“In the rest of the world the debate is whether prisoners should vote,” said Christopher Uggen, author of the Sentencing Project report, professor at University of Minnesota, and the country’s leading expert on felony disenfranchisement.

In the US, the history of felony disenfranchisement has been closely tied to racial oppression and discrimination. The laws have been part of American history from the country’s inception, but their spread took off after the Fifteenth Amendment gave black people the right to vote in 1870. Laws passed barring felons from voting during the 1860s and 1870s were the“first widespread set of legal disenfranchisement measures that would be imposed on African-Americans,” write Uggen and his colleagues Jeff Manza and Angela Behrens in a study about the history of the practice.

Although momentum to loosen disenfranchisement is gaining steam today, resistance to change the laws is fierce, as the case of Virginia shows. Indeed, Alabama was just recently accused in a federal lawsuit of racial discrimination because of how it enforces disenfranchisement of felons. One-third of states had wide felon disenfranchisement laws in 1850–now most do. “It really is a vestige of the sort of voting restrictions that were common in the 18th, 19th century,” Uggen said. Other barriers, such as gender, race, or wealth have fallen, one by one. “The stigma of crime is the hardest to overcome,” the researcher says.

How many ballots are we talking about?

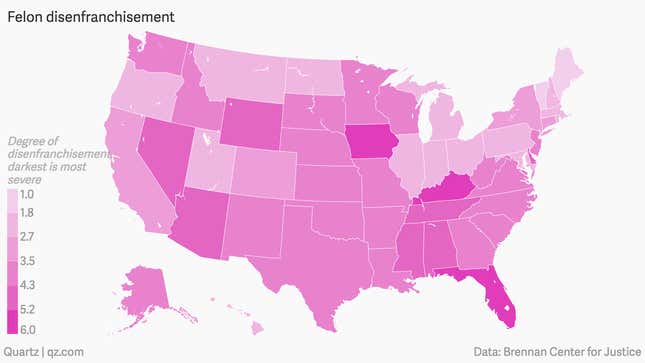

Because states decide whether felons vote, the implications of felony disenfranchisement vary greatly across the country. In three states–Florida, Iowa, and Kentucky–ex-offenders are essentially banned from voting for life, unless they get an exemption from the state’s government. In most states, the ban encompasses those on probation or parole, sometimes both. Often, felons are prohibited from voting until they’ve paid all of the financial obligations related to their case. In a handful of states you can vote as soon as you’ve completed your time behind bars.

The disenfranchised can be a large proportion of a state’s potential voting population. If we counted all the felons in prison as well as the estimated the number of ex-offenders, in some states they could swing an election–if they could vote. In Florida, this share could be as high as 10% of the entire population.

Most of the discussion about felon disenfranchisement centers on ex-offenders, not those behind bars. Of the entire disenfranchised population, less than one-fourth are in prison–51 % have completed their sentences, according to The Sentencing Project, but still can’t vote. Assessing the precise number of these ex-offenders is difficult—researchers can only estimate these numbers, because the government does not track ex-felon populations over time, taking into consideration their deaths, migration or recidivism.

The felon and ex-felon populations may be large, but how many of them would actually turn out to vote? Overall turnout in recent US presidential elections has varied from 48% to 57%, but it’s safe to assume that the felon population would have a much lower rate of participation, considering their backgrounds, and the fact that repeated contact with the criminal justice system reduces the likelihood of voting, as political scientists Vesla Weaver at Yale University and Amy Lerman at Berkeley University find in their research.

Uggen and Jeff Manza estimate that turnout among felons would average 35% (although in states that allow ex-felons to vote, sometimes their turnout was as low as 10%) But even at a low level of participation, it’s possible that felons could have swayed a number of elections where the margin of victory was small.

Which party is hurt by felony disenfranchisement?

Researchers estimate felon and ex-felon turnout and voting choices by matching the voting patterns of populations that are similar to them in their gender, race, age, income, education, marital and employment status.

Generally, they find that Democrats are most hurt by felony disenfranchisement—a belief held by politicians as well. Nationally, those who are imprisoned are disproportionately African-American, a crucial Democratic constituency. About 40% of all inmates are African-American, and an estimated 36% of all of those disenfranchised by a felony conviction are black. This population is likely “going to be a largely urban, largely young demographic group, largely male,” said Weaver. While it’s unclear exactly how large of a share of all disenfranchised felons constitute Latinos, who also generally prefer Democrats, we can assume it would be in the area of 20%, which is the share of Latinos in the current inmate population.

The picture is more complicated for the white felon population, who are generally poor. The median income of white inmates before they enter incarceration is $21,000. And low-income white voters have voted for both major parties in the recent past. In 2008, 51% of white voters with an income below $50,000 chose John McCain. Between 2008 and 2012, there’s been a significant pivot toward the GOP among low-income and less educated whites.

All that being said, the share of disenfranchised felons and the racial distribution of inmates varies significantly from state to state, so potential outcomes of granting them the right to vote have to be considered on a state level.

According to Uggen and Manza, there’s a number of elections where Democrats have suffered as a result of felony disenfranchisement. They believe that because felons couldn’t vote, Republican candidates had a “small but clear” advantage over Democrats in every presidential and senatorial election cycle from 1972 to 2000, including races in Virginia, Georgia, Texas, Kentucky, and Wyoming.

The most notable, and most debated, is the 2000 election that put George W. Bush in the White House. He won over Democrat Al Gore by gaining Florida’s 25 electoral college votes by 537 votes in the popular election.

In 2000, Florida had more than 827,000 inmates and former felons who weren’t permitted to vote. Uggen and Manza estimate that 68.9% would have voted Democrat. They estimated the turnout at 27.2%. That would have given the Democrats an extra 155,025 votes and Gore would have won over Bush by almost 85,000 votes. Even if turnout among felons and inmates was just 13.1%, Gore would have scored enough extra votes to have won Florida and the presidential election.

Not everyone agrees with Uggen and Manza. Traci Burch, political scientist and assistant professor at Northwestern University, says that because Florida’s felon population was largely white, the majority would have voted for Bush, and the result of the election would have remain unchanged. The discrepancy stems partly from the question mentioned above: Who would white felons vote for if they could?

What about the 2016 election?

Current polls say that black and Latino voters aren’t backing Donald Trump. He is attracting white, uneducated voters, but according to FiveThirtyEight, the polling website, only 12% of Trump voters have incomes below $30,000. According to the Pew Research Center, the poorest white voters—the group that best matches the overall white prison population—are split evenly among Republicans and Democrats, with the majority (38%) registered as Independent. Uggen speculates that the partisan effect of felony disenfranchisement on this election could be “somewhat muted,” because of the poor whites’ shift to the GOP.

Burch, who disagrees with Uggen and his colleagues about the effect of felony disenfranchisement in the past, points out that what matters is the proportion of them state by state. She wrote in 2010: “The impact of disenfranchisement on future elections is uncertain not only because of the changing size of the disfranchised population, but also because of the changing demography. Although most ex-felons are white in many states, recent cohorts of offenders have become more racially diverse. In Florida, for instance, while black men and women make up only 35% of the ex-felon population, 41% of people currently being supervised for felony convictions are black.” (35% refers to those who completed their sentences, and 41% to those in prison, probation or parole).

She also notes that turnout could be higher with increased awareness: “To the extent that disfranchisement remains prominent on the public agenda, offenders may be mobilized to vote.”

One thing is certain: If felons were allowed to vote, they would be a force to be reckoned with in the 2016 election. Florida and Iowa are among the battleground states this year with the strictest laws on voting by convicted felons. In Florida, as many as 1.5 million people are disenfranchised because they were convicted of a felony. In Iowa, it’s about 56,000 individuals. In Wisconsin, it’s more than 62,000. All of those are significant shares of the states’ voting populations.

It’s about more than just about numbers

Hillary Clinton has actively sought to give felons the right to vote since 2005, when she co-sponsored a bill called “Count Every Vote,” which died in Congress. ”I think if you’ve done your time, so to speak, and you’ve made your commitment to go forward, you should be able to vote and you should be able to be judged on the same basis,” Clinton said in 2015. “You ought to get a second chance.”

Although we can only hypothesize whether giving ex-felons and felons the right to vote would sway the pendulum in the Democrats’ direction, research shows that it is likely. But felony disenfranchisement has consequences beyond the final vote tally.

Losing one’s voting rights perpetuates feelings of alienation, distrust of government and a feeling of powerlessness. It makes the disenfranchised less likely to engage with or contribute to their community. Weaver and Lerman found that wherever individuals are deprived of voting rights, their families, neighbors, fellow church members don’t go to the polls on election day either. That six million population who doesn’t vote because of its involvement with the criminal justice system can become much bigger.