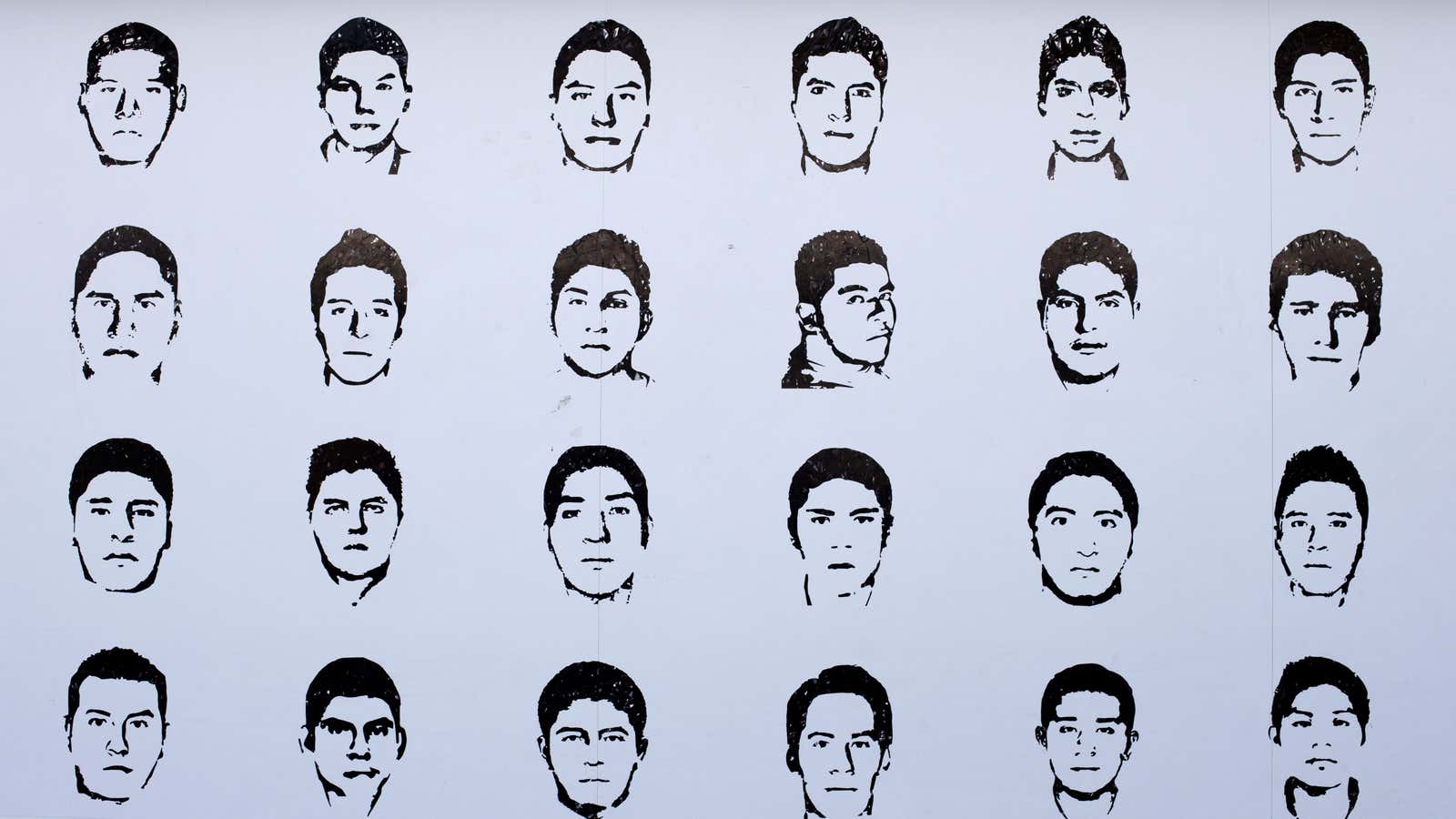

It’s been two years since 43 students from a teacher’s college in the Mexican state of Guerrero went missing and there’s still no trace of them.

On Sept. 26, 2014 they disappeared on their way to a protest. A few months later, the government claimed they were killed and burned at a dump by a drug cartel that believed the students were members of a rival group.

Since then, though, forensic science has largely disproved that theory, and could eventually provide some answers to the grief-stricken families of “the 43,” as the victims are known, and millions of outraged Mexicans.

Pigs in a pyre

The Mexican government enlisted an independent group (link in Spanish) of international investigators to help with the probe. They, in turn, enlisted José Torero, a fire scientist at Australia’s University of Queensland, St. Lucia, for help. Torero examined the dump site and didn’t find enough evidence of a fire big enough to render dozens of human bodies to ashes.

He confirmed his hunch through an experiment that involved lighting up pig carcasses atop pyres, reports Science magazine. What he and his team found was that even if the perpetrators had been able to gather up the thousands of kilos of wood needed to burn so many bodies, the fire wouldn’t have been strong enough to destroy most of the organic matter. Yet at the site, and in a nearby river where the attackers allegedly dumped their victims’ remains, all investigators found were ashes and a few pieces of bone.

Bone fragments

Those bone fragments were sent to the University of Innsbruck in Austria for analysis. Scientists there linked the remains to two of the 43 students (Spanish), seemingly bolstering the government’s theory that “the 43” were burned at the dump.

But another group of foreign experts, the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EEAF for its Spanish acronym) questioned that conclusion based on the evidence gathered so far, they said in a February report (Spanish, pdf.)

EEAF, which had been working with Mexican authorities on the probe, says the University of Innsbruck results are accurate but that they don’t necessarily back the fire theory. One of their identifications was based on highly-reliable nuclear DNA, but the bone fragment used came from the river, not the dump, and as of now there’s no clear connection between the two locations, according to the Argentine forensic experts. Additionally, it was in an unusually good state compared to all other organic material found, the group says.

The other identification was done using mitochondrial DNA—which the Innsbruck team itself says is only moderately certain. The EEAF notes that it therefore should not be considered definite proof that the student’s body was burned at the dump.

In its report, the EEAF cites several irregularities in Mexico’s investigation, including the fact that the alleged crime scene was left unguarded for a period of time. And although EEAF had started working alongside Mexican authorities, it was not notified when divers fished a bag containing a bone fragment—the one eventually identified with nuclear DNA—out of the river. The group has requested the custodial chain for that bag of evidence, but had not received any response from Mexican authorities, it said.

“We’re before an open case, in which the sites of remains recovery are uncertain and problematic,” added EEAF

Plane search

Faced with this new evidence, Mexican authorities have started looking into other possibilities beyond their initial theory.

Now they are looking for clandestine graves where the students might have been buried, using LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) a method that sends out laser pulses to obtain terrain information. Flying over an area, they can capture infrared and thermal images that can be analyzed for clues. “There’s a group of experts working on this 24 hours a day,” authorities told Mexican newspaper Milenio.

So far, though, they haven’t reported any sign of the 43.