Anyone paying attention knows Qatar has a foreign labor problem.

Specifically, the 300,000 citizens of oil-wealthy Qatar rely on 1.3 million guest workers from other countries for most labor needs. Report after report from human rights and labor organizations say they are mistreated at best, and exist in a “21st century slave state” at worst.

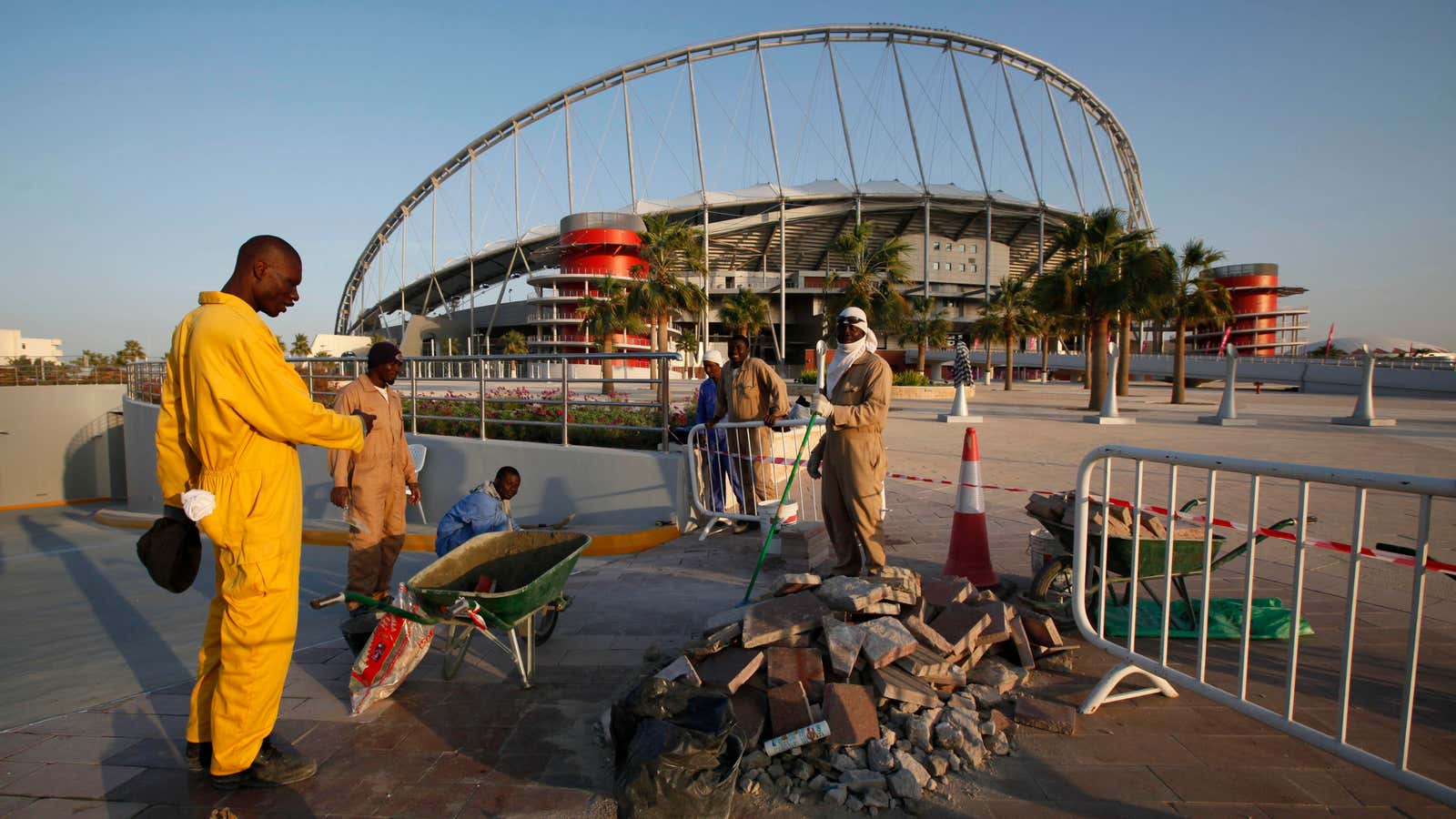

Qatar won the rights to host the 2022 World Cup under some dubious circumstances—how else do you arrange to host an athletic competition in 100°F heat? But while the competition brings prestige and attention to the state, it has also brought a lot of scrutiny to all the laborers—perhaps an additional million people—working to build stadiums and other facilities for the event.

And because FIFA, the international soccer organization, is standing behind Qatar, the spotlight is reaching beyond the typical migrant laborer.

CNN has the story of two professional soccer players who say they’ve been caught up in the country’s migrant worker system. Abdeslam Ouaddou, a Moroccan who has played in the world’s elite leagues, says that a Qatar soccer club withheld his exit visa, trapping him there until he withdrew a complaint to FIFA about withheld wages. The other, Algerian international Zahir Belounis, says he is still trapped in Qatar, denied both his wages for playing for a team there, and an exit visa in a contract dispute. (Ouaddou is now in France, and CNN says the Qatari Football Association declined to comment on any of the allegations.)

Advocates for workers point to a number of problems in Qatar’s guest worker law, but the worst is the kafala system, which ties workers to specific employers who have the power to withhold their exit visas. That means foreign workers are entirely at the mercy of their employers, who can prevent them from working elsewhere or leaving the country. (In a parallel, reformers attempting to fix US temporary worker visas want to end similar employer ties, although American businesses cannot compel their workers to stay in the country.)

Combine the kafala system with little ability for workers to access Qatar’s legal system and misleading recruitment practices, and you have a recipe for exploitation. As part of the agreement to host the World Cup, Qatar promised it would improve the situation for migrant workers, but in the two years since, human rights organizations say it has made little real progress.

While there appears to be little danger of Qatar actually losing the Cup over its labor violations, both FIFA and the country’s rulers will face more negative attention from the media and the international community over their worker problems (and their relationship with former French president Nicolas Sarkozy) than they would like.

It’s just not that easy to host a World Cup anymore.