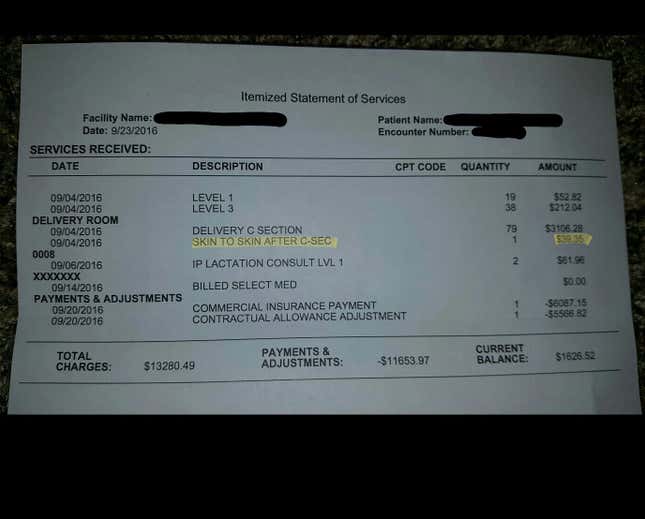

Ryan Grassley, a new father in Utah, recently uploaded a photo to Reddit of the hospital bill he and his wife received after the birth of their son. The post, which went viral, captured a circled line item labelled “skin to skin after c-sec,” with the accompanying comment: “I had to pay $39.35 to hold my baby after he was born.”

A spokeswoman for the hospital where the baby was born has since addressed the $39.35 charge in a statement, explaining that the charge reflected the added cost for a nurse to be in the room making sure that mother and child were safe. Many hospitals in the US now encourage skin-to-skin contact, in part to help a mother and baby bond. But because the patient is typically groggy following surgery, administrators say extra supervision is needed.

Still, the skin-to-skin fee hit a nerve. As one Reddit user wrote:

Hey, I know this world: we had to pay $700 for our son to stay in my wife’s room. Here, I’ll explain: my wife was billed $700 per night after her c-section, and my son was also billed $700 per night for his room.

Here’s the kicker: they shared the same room!!

That family was also charged for double the number of nurses attending to them, the commenter reported, even though the baby didn’t have his own nurses.

Another Reddit user added:

I have twins but when I was pregnant my ultrasounds were billed double “fetus” and “additional fetus”. I believe my section also cost double which annoyed me because you don’t have to prep and cut me twice. Just reach back in and grab whoever is left!!

Multiples are definitely not buy one, get one free.

And on Twitter:

As US healthcare costs have skyrocketed, more patients feel a sense of panic and dread about how to control their bills.

For American parents, the cost for a hospital birth can be astronomical and unpredictable. After comparing prices in 30 major cities, Castlight, a health care data company, recently found that the average national cost for a vaginal delivery is $8,775, but went up to upwards of $15,000 in San Fransisco. The average c-section cost $11,525, but exceeded $42,000 in Los Angeles.

Price-shopping also isn’t an option. Researchers from Healthcare Blue Book, who conducted a pricing survey in 2010, found that 70% of the hospitals they called regarding specific surgeries would not provide a guaranteed price, and 18% wouldn’t return calls or disclose pricing.

Unpredictable charges are a quagmire in US healthcare. In a 2013 feature story for Time, Steven Brill explained how high fees for even over-the-counter drugs dispensed by nonprofit hospitals are set by something called the “chargemaster,” an internal list of thousands of prices that every hospital keeps and that is unique to each hospital. Outside of Medicare expenses, hospital fees are not regulated, so administrators are able to use extreme markups without justification.

The chargemaster explains all of a hospital’s prices, from child delivery to the $1,000 toothbrush. It’s what leads to fees like $15 for a single Tylenol pill, $8 for a grocery bag to hold your personal items, $8 for a box of Kleenex—which is sometimes listed as a “mucus recovery system”—or $10 for a small paper cup used to dole out medications.

Brill argues that there is “no process, no rationale, behind the core document that is the basis for hundreds of billions of dollars in health care bills.” In his quest to explain the reasoning behind chargemaster prices, he found that officials treat it as if it were “an eccentric uncle living in the attic”—i.e. out of their control and not open for discussion.

Medicare has calculated prices that consider all of a hospital’s reasonable costs, including investments in technology, salaries, and the cost of living by location. Chargemaster prices, which are typically about 300% higher than what Medicare pays (though some can be more than 1,000% higher), allow nonprofit medical facilities to spend on gleaming new facilities and six- or seven-figure salaries for top administrators. Meanwhile, those prices have driven up insurance premiums and deductibles for everyone—including employers.

The Affordable Care Act has yet to address the problem. Speaking at an annual Connecticut State Medical Society meeting last month, Brill explained that while the reforms have given more people insurance, they haven’t tackled hospital costs. Instead, high fees built into the system are falling onto taxpayers.