The generation that grew up with Nike Dri-FIT is making dress shirts you could run a marathon in

In an era where jeans are stretchy and yoga pants are office attire, one might spare some pity for the men still confined to dress shirts.

In an era where jeans are stretchy and yoga pants are office attire, one might spare some pity for the men still confined to dress shirts.

With buttons down the front and a stiff, folded collar to accommodate a necktie, there’s a ceremonial primness to this garment. What’s important is how it looks, not how it feels or what it does.

The last major breakthrough in dress shirts was the non-iron version, introduced in the early 1950s. Since then, despite the many ways technology has altered the office—and textiles—the dress shirt hasn’t changed much. It’s still typically made of cotton, polyester, or some blend thereof, and it’s still a garment meant for sitting, standing, and walking—not much good for running, jumping, or biking.

But a handful of companies, including Ministry, Mizzen + Main, and Nanotex, are trying to shift that paradigm. Inspired by performance qualities you’d typically expect of athletic clothing, they are trying to give the dress shirt a functional upgrade. They want it to keep you cool, to wick away moisture, to stretch and breathe and be more comfortable than your off-the-rack cotton button-up in a variety of conditions. It’s office clothing for the generation that grew up with performance fabrics, such as Nike Dri-FIT.

Dress shirt 2.0

The problem with most everyday dress shirts is that if you sweat at all—and many guys do—your shirt can quickly become a soggy mess, which feels awful when you walk into an air-conditioned office and looks even worse.

“I had watched a guy run into a building soaked in sweat and thought, ‘Why not make a dress shirt out of performance fabrics?'” says Kevin Lavelle, who founded Mizzen + Main in 2012. Lavelle’s solution was to create shirts made with moisture-wicking polyester that draws sweat away from the skin and dissipates it, helping to keep the wearer dry. The shirts also have stretch for comfort, and they’re wrinkle-resistant, making them good for traveling.

Aman Advani and Gihan Amarasiriwardena, who launched Ministry with Kit Hickey in 2012 were athletes who grew up on performance materials. (The company recently rebranded from the longer title Ministry of Supply, and just launched women’s wear.)

“That’s just the normal thing: I’ve got a Nike Dri-FIT shirt and a pair of Under Armour shorts,” Advani told Quartz in an interview last year. In a publicity stunt last December, Amarasiriwardena ran a half-marathon in a Ministry suit to show off the clothing’s athletic abilities.

For their shirts, they use various polyester and cotton blends, but the company looks beyond just athletic wear for ideas. Among the fabrics it uses is a phase-change material (pdf) that NASA developed for astronauts, who endure extreme temperature swings as they move in and out of sunlight. It’s meant to help regulate body temperature when, for instance, you walk into a freezing office after being outside on a hot summer day.

They say their clothes are based on a process-focused approach, rather than tech for its own sake. ”It’s about understanding how your body expels heat, pressure, odor, moisture, how your skin stretches,” Advani explains.

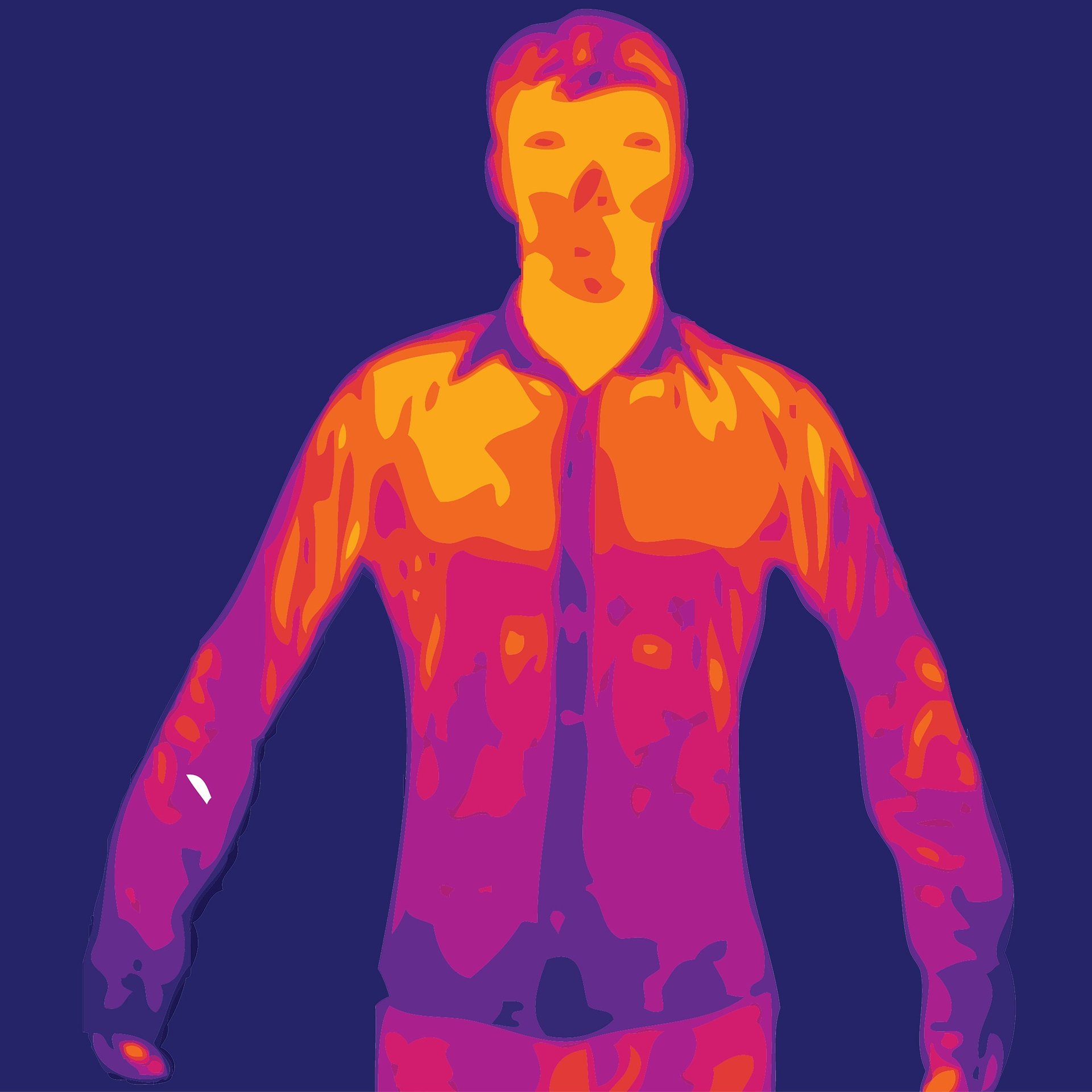

For instance, to determine what the literal hot spots are on most people they used thermal imaging and found many people expel heat at the back of the armpit. They added tiny laser perforations in that spot on their shirts, which they say lets heat escape more easily.

So, do they work?

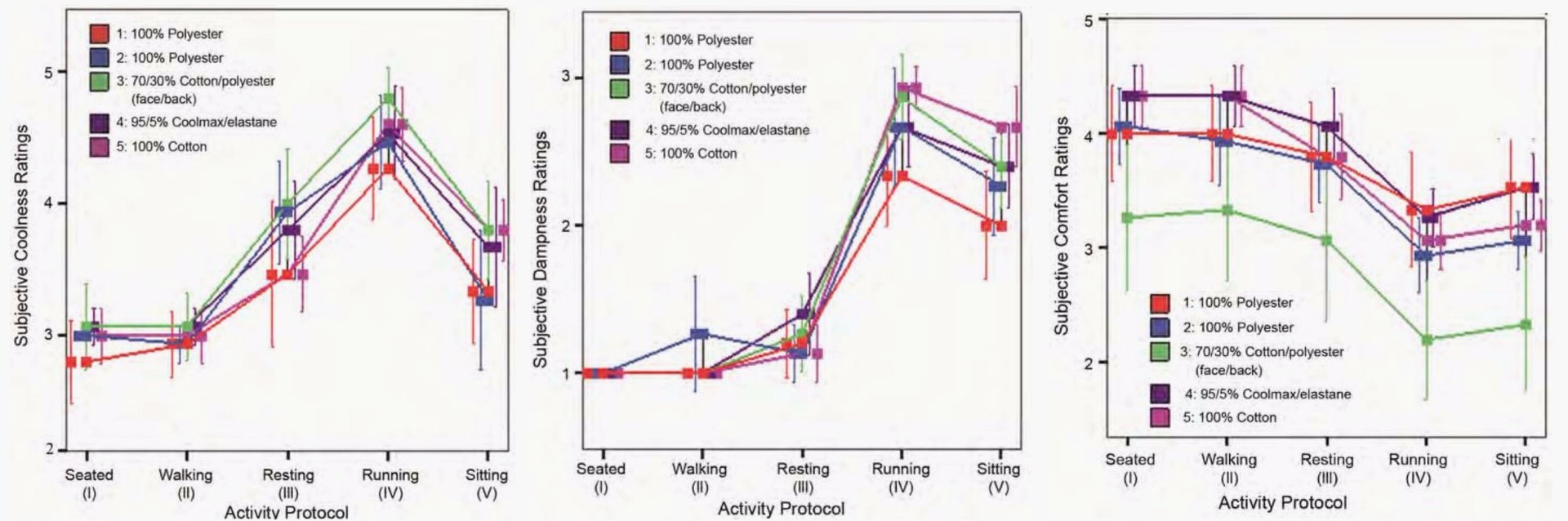

There isn’t a lot of independent research on how well performance fabrics, well, perform, but the studies that have been done suggest there’s little evidence they do much to keep a person’s body thermostat steady—whether he’s an athlete or an office worker. A 2003 study of different fabrics on athletes during exercise didn’t find any discernible effect on body temperature, regardless of fabric type. Similarly, a small 2011 study (pdf) that had subjects carry out different activities found that fabric type didn’t significantly affect skin temperature. More recent research did find cooling benefits, but it focused on athletes engaged in strenuous exercise. (One study on phase-change materials like those that Ministry uses in some products concluded they can stay cooler.)

Where performance fabrics shine is in keeping you feeling dry, particularly after some activity that makes you sweat. The difference can be noticeable. In that 2011 study, subjects were also asked for their subjective experiences, and they reported feeling less damp in polyester than in cotton after running. It makes sense: Cotton is hydrophilic, meaning it absorbs water. (One drawback of polyester is that it gets smellier than cotton. Another is that it leeches polluting plastic fibers when washed.)

At a distance, you can’t easily tell that these shirts aren’t made of a typical cotton broadcloth. But the difference is immediately clear when you touch them. Mizzen + Main’s shirts, for instance, have the slippery feel common to synthetics. Polyester, a key fiber in performance fabrics, is plastic, after all. The material may not be everyone’s preference, and Brooks Brothers will continue to have plenty of business for its staple cotton shirts.

Riding the wave of athleisure

Lavelle says his customers aren’t put off. ”Because of Nike and Lululemon and Reebok and Under Armour, our generation has fully embraced everything synthetic,” he says. Not surprisingly, the Mizzen + Main shopper tends to be athletic, and the brand has hired several athletes to represent it.

The aesthetics of the shirts aren’t breaking any new ground, but that’s hardly the point. They’re functional there, too, in the sense that they fit easily into the preexisting notion of how office clothes should look. They’re ideal for guys who probably don’t want to wear a dress shirt, but feel they have to. Sure, office dress codes continue to break down, but plenty of workplaces still want their employees at least wearing business casual.

Nanotex is different in that it doesn’t make any shirts itself. It takes an existing fabric, such as 100% cotton cloth, and dips it in a chemical bath tailored to the specific fiber, according to CEO Randy Rubin. It dries the material in something like an oven, and the fiber itself is altered, with the new traits baked in. It’s not a topical solution that can wash off, like the usual non-iron treatments.

“It’s now changed at a molecular level,” Rubin says. “It is not topical at all. It’s part of the fiber.” They supply a raft of fabrics with different traits—odor neutralizing, water repellant, moisture wicking, and more—to companies including Calvin Klein and Van Heusen, which use them to make their own products. (Nike, incidentally, uses Nanotex’s Wick+Block technology for its nylon NFL jerseys.)

Even though synthetic performance fabrics have been around for decades, it took advances in their look and feel and arguably the embrace of sporting goods companies to make them part of the everyday wardrobe. Nike’s introduction of Dri-FIT in 1991 had a lasting impact on Lavelle, Amarasiriwardena, Advani and other men and women like them. Non-athletic clothing brands have been experimenting with these fabrics for some time, but it may have taken the rise of athleisure to really kickstart demand.

“After the whole athletic movement started, there’s just this inclination to think, ‘If I can do this on my t-shirt, if I can do this on my raincoat, why can’t I do this on my shirt?'” Rubin says. “And the retailer needs a competitive advantage.”

Debates over temperature control aside, emphasizing performance qualities has helped these companies gain a foothold in the market. Mizzen + Main has expanded from 40 retail stores to 275 in the last year and a half, helped by its collection of $125 shirts. Ministry, which has attracted investors such as Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh, will have expanded from two stores at the start of the year to seven by its end. The company’s best-seller is its $95 Daystarter dress shirt. Calvin Klein’s “STEEL” performance shirts, made from Nanotex’s fabric, can be found at Macy’s, where they cost $75.

Reimagining the dress shirt may seem like reinventing the wheel, but in a crowded market, it’s near impossible to break in without a product that stands out, or has some special feature.

“If I didn’t create a performance-fabric dress shirt, I would not be in this industry,” Lavelle says. “When we say, ‘It’s like a Dri-FIT dress shirt,’ they say, ‘Oh, that makes sense.'”