Driverless cars are often presented as a futuristic, science fiction-esque concept. But in fact, they’re old —almost archaic — and first drove along the road almost a century ago. The very first driverless car, known as the “American Wonder,” travelled down New York’s Broadway in 1925. The unmanned vehicle was operated by radio control and attracted excitable crowds and police escorts on motorcycles as it made its journey to Fifth Avenue.

The car, made by the Hulett Motor Car Company, was slightly less impressive than the autonomous vehicles Google is working on today. Its human operator had to remain less than 50 feet away, and controlled the empty car from a second vehicle driving immediately behind. But nevertheless, the invention shows a long history of successful experimentation with driverless cars.

In fact, though the 1925 American Wonder very first driverless car, it was far from the first unmanned vehicle. According to H.R. Everett, author of Unmanned Systems of World Wars I and II, the first unmanned ground vehicle was a radio-controlled tricycle made by Spanish inventor Leonardo Torres-Quevedo in 1904. Then, throughout World War I, militaries used various small, radio-controlled vehicles to deliver and detonate explosives. And a “mystery motor car” drove through New York at 1.4 miles per hour in 1921. This wasn’t really a car, though, Everett explains. It was called a “car” (or a “wagon”) simply because it had four wheels—it looked nothing like a car in the contemporary sense of the word and, at just five feet long, as was not large enough to carry any passengers.

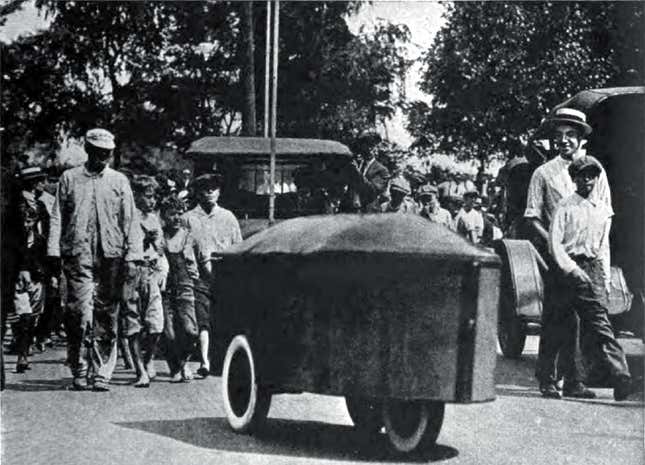

A similar, though slightly larger, vehicle drove through Dayton, Ohio, in 1921, as the QI podcast, No Such Thing As a Fish, recently noted. “Hundreds of people… stopped in amazement,” reported a publication called Electrical World, to watch as the driverless “car” travelled along followed by its operator. “As the car approached street intersections traffic signals were observed, and the horn was blown if some pedestrian or other obstacle got in the way,” notes the article.

At the time, driverless cars were a novelty to test and demonstrate the accuracy of radio control.Though radio controls could be effective at significant distances (the inventor of the Ohio driverless car, Raymond E. Vaughan, claimed that “the controls would be effective at a distance of 50 miles”), the driverless car’s operator always had to be close at hand to spot and respond to obstacles.

“It attracted a lot of interest but there was really no practical application for it,” says Everett. “What good is a radio controlled car that you have to be within 50 feet to control and you have to follow in another car? They knew that at the time, it was just, ‘Hey, this is what we can do now and you can project to the future when you’ll be able to do it better.’”

Though there’s considerable interest in driverless cars today, the history of unmanned vehicles is largely forgotten—it took Everett 10 years to research his book. “A lot of this stuff was only demonstrated locally to a few people in a city,” he says. “Maybe there was a newspaper article, maybe not, but the newspapers were typically only local, so the word didn’t spread like it does today. Eventually people forgot about it.”

And though unmanned radio controlled vehicles were widely used and practical in both world wars, that was a history most people were eager to forget. “After the war, no one really wanted to talk or think about military weapons anymore,” says Everett.

There’s very little technological link between the early driverless cars and the contemporary efforts of Tesla, Google, Uber, and others. The actuators used to turn electrical signals into mechanical actions to control the steering and brake in the driverless cars of the 1920s are an early precedent to those used today. But in general, says Everett, “the research started all over again from a totally different perspective.”

Though the tech for autonomous driverless cars is very different from the radio-controlled vehicles, Everett expects modern creations to have a bumpy early ride, just like the first driverless cars 90-odd years ago. “In the beginning there were a lot of problems, as there always are, with reliability and range, that type of thing,” he says. Contemporary driverless cars will also have to work through their own technological kinks before they can be truly useful.

“The problems they’ll have initially will be fairly significant but ultimately they’ll be overcome,” says Everett. “I think clearly this is the way of the future.”