China worked its way into the US presidential debate, even on the topic of abortion

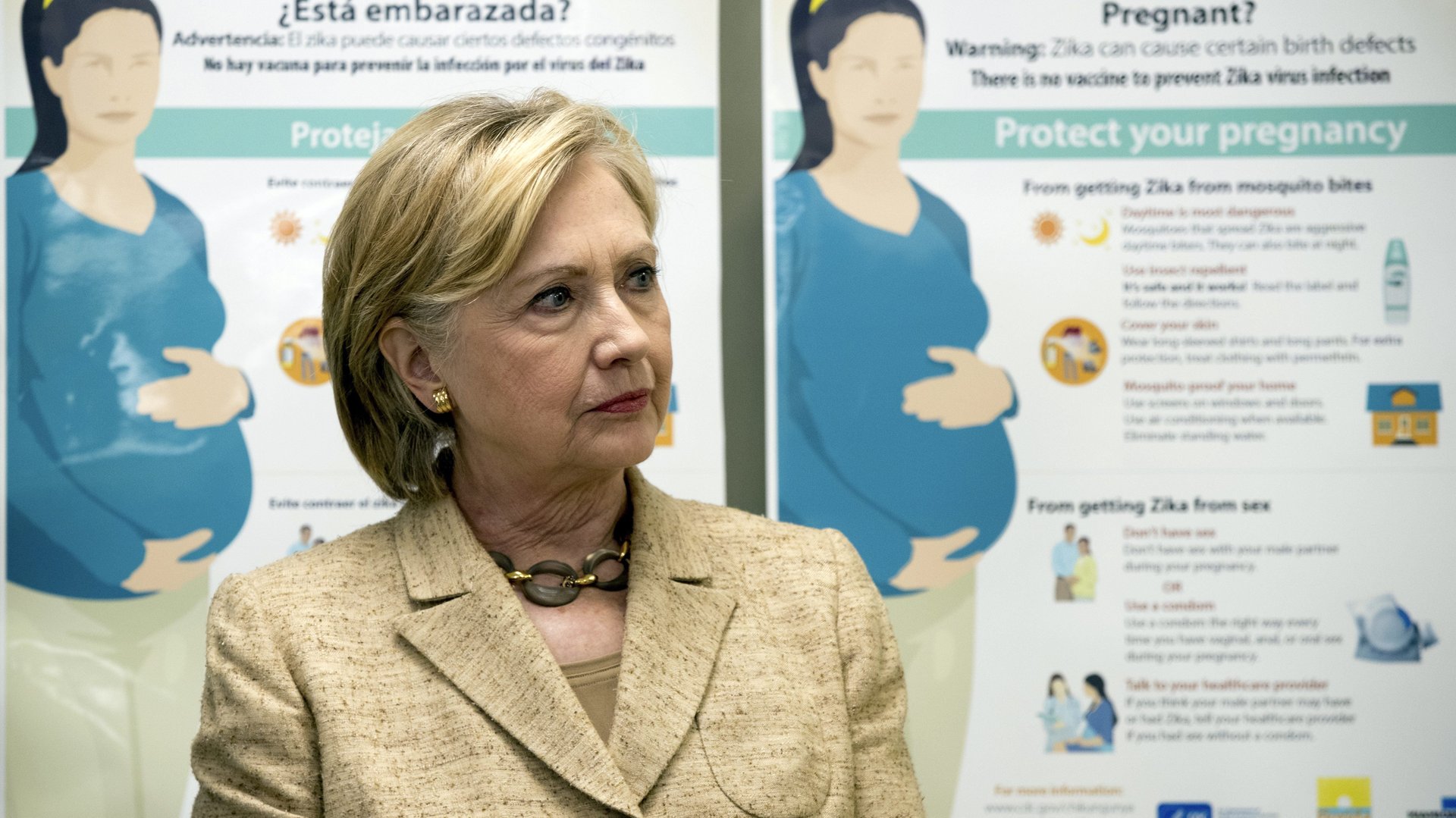

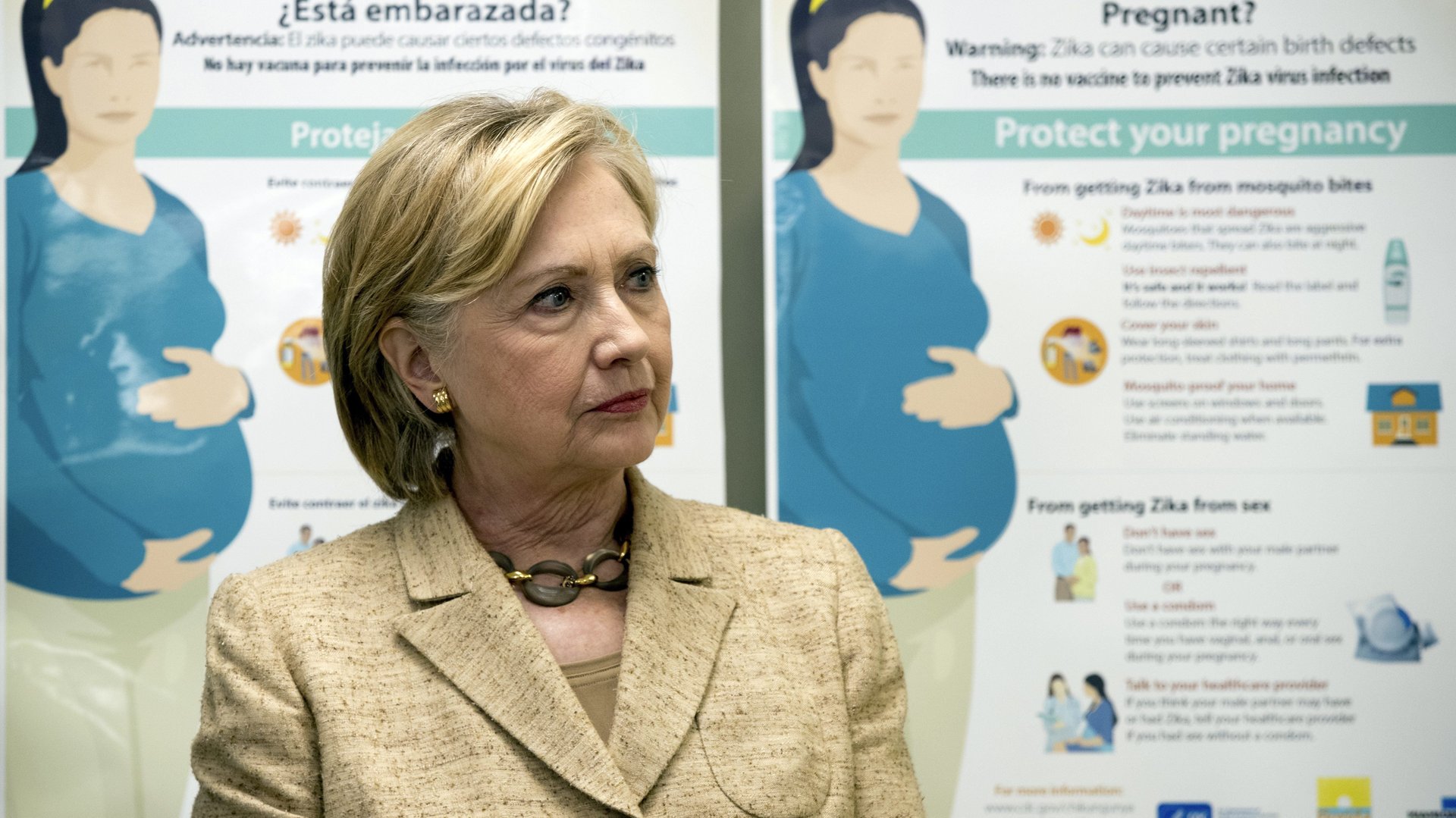

China has loomed large in the US presidential election this year, but usually on matters of trade. Last night during the third and final debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, China crept into another topic: abortion.

China has loomed large in the US presidential election this year, but usually on matters of trade. Last night during the third and final debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, China crept into another topic: abortion.

Trump said, “If you go with what Hillary is saying, in the ninth month, you can take the baby and rip the baby out of the womb of the mother just prior to the birth of the baby.” Clinton replied that such “scare rhetoric” was unfortunate and, in explaining her pro-choice stance, drew on the experiences other nations have had with abortion, including China. She said:

“I’ve been to countries where governments either forced women to have abortions like they used to do in China, or forced women to bear children like they used to do in Romania, and I can tell you the government has no business in the decisions that women make with their families in accordance with their faith, with medical advice.”

“Like they used to do in China” might lead some to believe that the Chinese government no longer interferes with decisions on childbirth. But in reality the state is still heavily involved in family planning.

For decades, China contained its population with a one-child policy (implemented in the late 1970s). Authorities required married couples to obtain what was essentially a pregnancy license (link in Chinese) from a local office of the National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC). Those who violated the policy faced a variety of punishments, from fines to job loss to forced abortions—what Clinton referred to. (In almost all provinces, it was and remains illegal for a single woman to have a child, and fines are levied for violations.)

Without a license, a pregnancy could be deemed illegal—and the resulting child would have trouble getting an identification card and going to school.

In 2013, China introduced an alternative two-child policy for some couples, eventually applying to all couples in 2015. That allows married couples to have two children instead of one, but authorities still require them to first register for a pregnancy, or pay “social compensation” fines (pdf, p. 54)—which could amount to three to 10 times (paywall) a household’s annual income. And children from unregistered pregnancies still face problems.

Local authorities set and enforce fines, leaving room for abuse. In 2012 officials in the Shaanxi province forced a woman seven months pregnant to have an abortion after she failed to pay a fine of 40,000 yuan (US$6,000). In response the state-backed tabloid Global Times condemned “forced termination of late-term pregnancies,” while also praising the one-child policy because it “freed China from the burden of an extra 400 million people.”

In 2015 China had around 13 million abortions, according to the NHFPC. By comparison the US, with about a quarter of the population, had around a million. But the Chinese numbers don’t include forced abortions, and, according to a 2015 report from the US State Department (pdf, page 55), “at least an additional 10 million chemically induced abortions were performed in nongovernment facilities.”

Not surprisingly, perhaps, it’s more common to see an ad for “painless abortions” than for condoms in China.