The first time I heard the lie, I was in fifth grade. Mr. Ward took me aside (or maybe he told the whole class, it was a long time ago) to tell me about the wonders of Dvorak, a different keyboard layout that was scientifically designed to be more efficient than the standard layout. That layout was called QWERTY, he explained, and it had been created to slow typists down. You see, in the olden days, mechanical typewriters could get jammed if people hit the keys too quickly, so they had to put the common letters far apart from each other. The modern keyboard, I was told, was a holdover of the mechanical age.

Since then, I’ve heard this story repeated a thousand times. So many times, I had assumed it was true. But Jimmy Stamp over at Smithsonian points to evidence released by Japanese researchers that, in fact, the story is bunk. The QWERTY keyboard did not spring fully formed from Christopher Sholes, the first person to file a typewriter patent with the layout. Rather, it formed over time as telegraph operators used the machines to transcribe Morse code. The layout changed often from the early alphabetical arrangement, before the final configuration came into being.

The researchers tracked the evolution of the typewriter keyboard alongside a record of its early professional users. They conclude that the mechanics of the typewriter did not influence the keyboard design. Rather, the QWERTY system emerged as a result of how the first typewriters were being used. Early adopters and beta-testers included telegraph operators who needed to quickly transcribe messages. However, the operators found the alphabetical arrangement to be confusing and inefficient for translating morse code. The Kyoto paper suggests that the typewriter keyboard evolved over several years as a direct result of input provided by these telegraph operators.

That is to say, the lesson of the QWERTY story remains the resilience of a design created for an outmoded technology’s dictates. QWERTY is still an example of technological momentum. But the development of the design wasn’t accidental or silly: it was complex, evolutionary, and quite sensible for Morse operators.

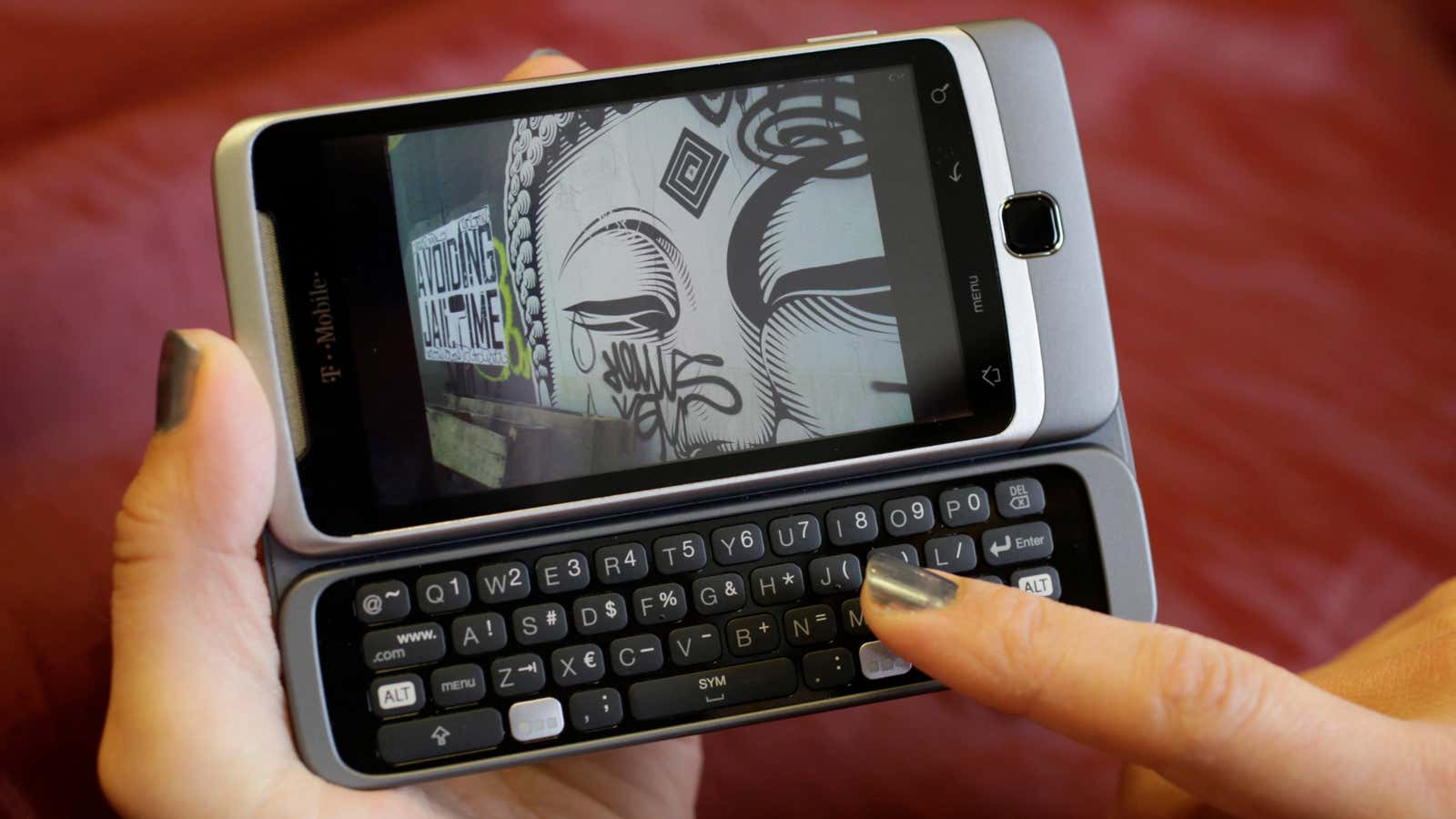

Keyboard configurations are newly important as we think about how we should type on tablets and other devices. The calling card of the personal computer was the keyboard, and now, we are carrying around pieces of glass on which we simulate the old QWERTY design. Are we going to keep that layout going? Perhaps QWERTY will always be good enough. But if not, how might a new design develop?

Alexis Madrigal is a senior editor at The Atlantic, where he oversees the Technology channel. He’s the author of Powering the Dream: The History and Promise of Green Technology.

This originally appeared on The Atlantic. Also on our sister site:

How US government raises unemployment and hurts the recovery