Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o did not win the Nobel Prize in Literature, yet again. For years, the Kenyan writer has topped the list of contenders at betting sites, rivaling Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami, or with the case this year, American novelist Don DeLillo. But on Oct. 13, the Swedish Academy presented the prize to the American singer-songwriter, Bob Dylan, whose reticence about the award since has been called “rude and arrogant,” and has left many wondering if he will ever accept it.

But Ngũgĩ should have won the award–not for the fame, money and global recognition that come with the prize–but because his literary and social activism has made Africa and the world a better place since his first book was published in 1964. For more than half a century, no amount of detention, harassment, prohibition or exile has deterred Ngũgĩ, whose writing has continued to broaden and influence a new generation of thinkers and writers.

A win for Ngũgĩ would also have been a win for Africa. For decades, Ngũgĩ’s novels, plays, and essays have listened to the cords of the African conscience, addressing the issues of nationalism, class, race, and gender with energy and urgency. The breadth of his work is also almost unparalleled, bringing readers to a more varied historical and cultural backgrounds.

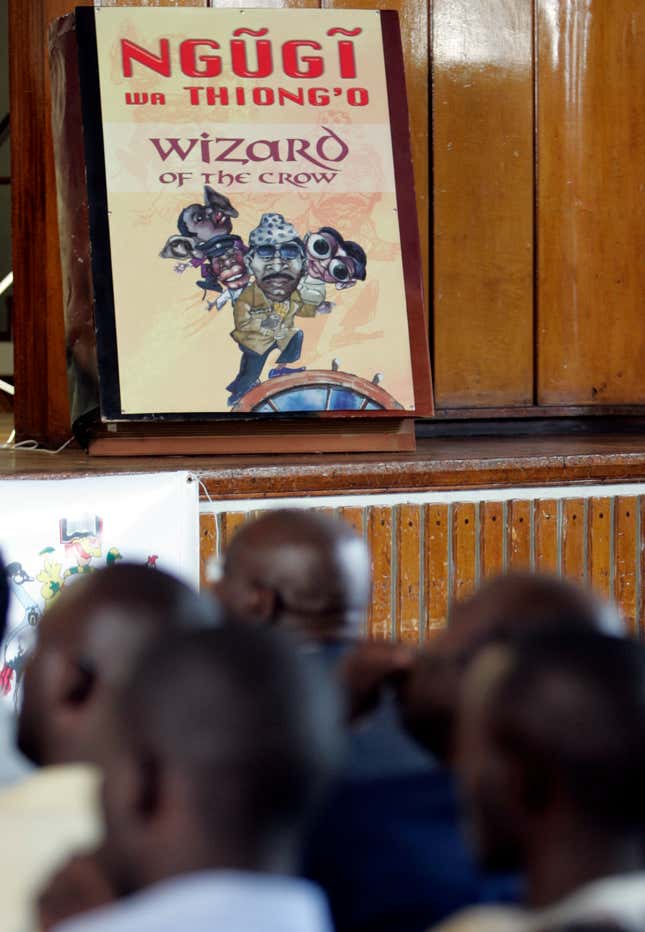

With precision and passion, Ngũgĩ has written about the struggle for independence (Weep Not, Child and Grain of Wheat), the effects of cultural and religious traditions (The River Between), the socio-economic problems in post-colonial Kenya (Petals of Blood), the grip of corruption and capitalism (I Will Marry When I Want), and the incongruity and irony of dictatorship across the African continent (Wizard of the Crow). His work has almost become a yardstick to measure the real progress–or lack thereof—of postcolonial Africa, and a rigorous analysis of the reality of those societies.

A win for Ngũgĩ would also have been a crowning achievement for African languages. To his credit, Ngũgĩ was the pioneer writer in the continent who propagated the idea that language was an extension of ourselves and that the elevation of English and the literature it introduced “were taking us further and further from ourselves to other selves, from our world to other worlds.” If slavery was the white man’s domination of the physical body, and colonialism was about territorial and land control, then the use of non-African languages was all about cultural subjugation and the internalizing of the values of the colonial power.

In a world where many African languages seem threatened with extinction, and English has become almost ubiquitous across the continent, one can’t help but wonder about Ngũgĩ’s declaration in Decolonizing the Mind, when he wrote, “It is the final triumph of a system of domination when the dominated start singing its virtues.”

In 1986, Ngũgĩ took his own advice and turned from writing in English to writing in his native Gikuyu, thus transforming the place of African languages in global literature. His magnum opus, Mũrogi wa Kagogo (Wizard of the Crow), which was written first in Gikuyu and translated to English by Ngũgĩ himself, is a testament to the use of African languages to tell our own stories. Wizard is a funny, witty book, full of hyperboles and biting truths that will keep you going, and make you think about Kenya’s dark past and its frustrating present.

Ngũgĩ should also have won the Nobel for the sake of his country: Kenya. Long after Ugandan poet Taban lo Liyong described east Africa as a “literary desert,” Ngũgĩ kept publishing, turning the prosaic into poetic, and disturbing the corridors of power and politics in the east African nation. In many ways, the Kenya of today is one that looks determined to forget the critical narratives of Ngũgĩ. Kenya has fast become a country where free expression is curtailed, where films are banned and streaming services are labeled a threat, where journalists are poisoned, killed and curtailed. The greed and corruption that Ngũgĩ captured so well in Wizard are so widespread in Kenya that even the country’s athletes, among the world’s fastest runners, can’t outrun its hold.

By winning the Nobel, the Swedish Academy would be sending a strong message to Kenyans and their leaders that goes: Look no further than in Ngũgĩ’s work to understand the problems ailing your country.

Four Africans have so far won the Nobel Prize in literature. Nigeria’s Wole Soyinka won in 1986, Egypt’s Naguib Mahfouz in 1988, and South Africa won twice, first with Nadine Gordimer in 1991, and then John Maxwell Coetzee in 2003.

If the Swedish Academy gives the award in the field of literature to “the most outstanding work in an ideal direction,” then Ngũgĩ is the man to beat. For his social and political criticism, for using truth as an organizing factor, and most of all, for applying African languages to tell stories with deep resonance, Ngũgĩ should have been awarded the prize this year. He is the writer Kenya, Africa, and the world need right now.