Leonard Cohen’s tortured love affair with Zen Buddhism

Leonard Cohen was waiting for the miracle to come, and he waited half his life away. For three decades, the Jewish poet pop star studied Zen Buddhism. At 65, he finally saw small miracles.

Leonard Cohen was waiting for the miracle to come, and he waited half his life away. For three decades, the Jewish poet pop star studied Zen Buddhism. At 65, he finally saw small miracles.

‘There was just a certain sweetness to daily life that began asserting itself,” Cohen told The Guardian in 2001. “I remember sitting in the corner of my kitchen, which has a window overlooking the street. I saw the sunlight that shines on the chrome fenders of the cars, and thought, ‘Gee, that’s pretty.'”

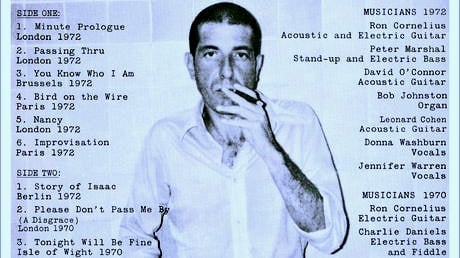

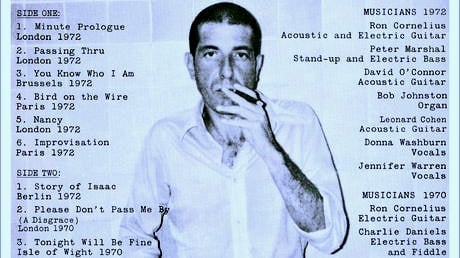

After a lifetime of sex, drugs, and rock-n-roll, the smoking poet leaned into this epiphany. In 1994, Cohen retired to the Mt. Baldy Zen Center in Los Angeles, California and was ordained as a monk in 1996. “I was interested in surrendering to that kind of routine…It is a great luxury not to have to think about what you are doing next,” he explained.

At the monastery, Cohen cooked, cleaned, and sat. Sitting meditation, known as Za-Zen, aims to tame monkey mind, frenetic thinking, by studying the self to forget the self. It worked for the songster. But it took three decades of instruction and the mellowing of old age to put the musician in a neutral, monkish state of mind. “When you stop thinking about yourself all the time, a certain sense of repose overtakes you,” he said. “It happened to me by imperceptible degrees and I could not really believe it.”

Cohen’s thoughts, which plagued him and became his poetry, inspired millions. He was the world’s most popular sad songster, along with Bob Dylan.

His death right after the American election is poignant. After all, it was Cohen, a Canadian, who described what is now evident in a song that he began penning in 1988 and released in 1992:

Democracy is coming to the USA

As the words suggest, Cohen was depressed for most of his life, despite his success. He didn’t always know what to say or what he meant, explaining in an interview with Throat Culture in 1992 that he wrote 50 versions and still wasn’t sure what the song was. “Is it a criticism of the US, is it a dream, is it an optimistic projection? Is it a protest or an affirmation? It doesn’t matter because the times when something comes to you so strongly are so rare and precious that you accept them.”

In the monastery, Cohen went by the name Jikan, meaning normal silence or ordinary silence. It’s a funny name for a man who spent his life filling silence with song, but perfectly in line with Zen’s preoccupation with plainness.

The practice prizes deliberate simplicity. In Zen, illumination isn’t elaborate or pretty. According to Zen parables, it can happen fast when a master hits a student on the head with a stick, chops a finger. Or it can happen slowly, when a student is expelled after many years of fruitless sitting. Enlightenment is plain, invisible to the untrained eye and unexciting for the mind. But when the student is ready, he must kill the Buddha on the road.

Cohen did this. He spoke on NPR in October, explaining that he left the monastery after five years because it was still “Boogie Street,” another place with no privacy and personal frictions. He took up music again.

This year, Cohen came home spiritually. Just before his passage, at 82, he released the album You Want it Darker in which he reinterpreted the Kaddish, a Jewish prayer for the dead. The song “Hineni” refers to the Torah, Abraham’s response when God asks that he sacrifice his son.

To the bittersweet end, Cohen wrestled with religion, all while submitting, singing: A million candles burning for the help that never came. You want it darker. Hineni, hineni. I’m ready, my Lord.