Last week, Google’s new Daydream View VR headset was released. It’s been getting mixed reviews. Some people love that it’s affordable, not made of cardboard, and comes with a handy little remote, while others are less convinced about having to strap a headset made out of seemingly the same material as a pair of sweatpants to their face. Regardless, it’s not entirely clear what you’re supposed to do with this device or those similar to it. Quartz spent the last week with the headset, and couldn’t really figure it out.

One big box retailer currently has about 20 headsets listed on its site that cost less than $150 and all do roughly the same thing: turn your smartphone into a mediocre screen through which to ingest virtual reality and 360-degree video content. They either rely on the phone’s built-in sensors or their own to track your head’s movement as you explore digital worlds. But unlike more powerful systems, such as Facebook’s Oculus Rift or HTC’s Vive, these smartphone-powered virtual-reality headsets leave a lot to be desired.

Google’s Daydream View, with all of its plushiness and marketing fanfare, isn’t really any different. It relies on the processing and graphics-rendering power of the smartphone that’s put in it. Even the newest, fastest smartphones are only so powerful. You’ve likely seen what 3D graphics look like in mobile games—they’re not exactly the immersive fictional virtual realities of The Matrix or even Tron—they’re blocky, choppy, and slow to render. This means that any VR games that are designed to run on smartphones are likely to be underwhelming.

Many of the VR games that Google has available to download right now take one of two approaches to gameplay: They either create small worlds in front of the user’s eyes that require the headset’s bundled-in remote to help move you around them—kind of like holding a snow globe at arm’s length—or they create fully immersive worlds that are purposefully blocky and lacking detail so that they can render effectively in real time. The former can be pleasing for a little while—I enjoyed killing demons and the like in Hunters Gate for a few levels and the mini-games of Wonderglade were enjoyable for a bit—but the latter can be really disorientating. Trying out VR Karts Sprint—which is a rip off of Nintendo’s Mario Kart in everything but name—and Polyrunner VR, a Temple Run-esque game where you see how far you can fly a spaceship before crashing, I found myself too dizzy to continue playing after a few minutes.

What’s the point?

It’s not entirely clear what the purpose of smartphone-powered headsets is. In a lot of the advertising around Daydream View and the Gear VR, we see people being impressed by whatever they’re looking at, but rarely do we see what they’re actually seeing. And that might be because there’s not much to actually do in VR right now. Playing mobile games that look and feel pretty similar to the ones that we already waste our commutes playing isn’t much improved when you strap a phone to your face to play them. These games are generally as weightless and simple as other mobile games, because these systems can’t handle truly immersive worlds.

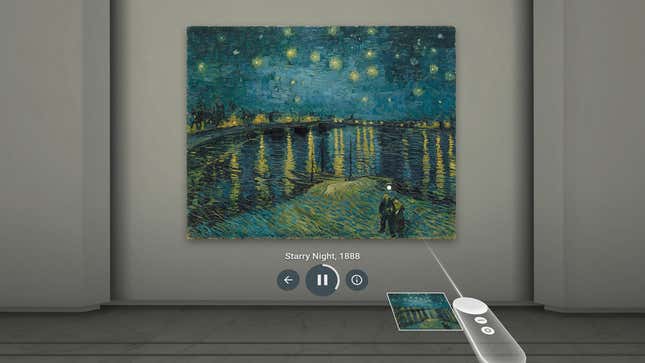

Beyond gaming, what is there really to do? Google is currently promoting a VR version of Street View, where you can click around famous landmarks that its camera cars have mapped out, but looking at 360-degree imagery on a phone screen an inch from your face isn’t wildly different than looking at those same images on Street View normally. Similarly, there’s an app called Arts & Culture that lets you view famous artworks on a wall in front of you. A lot of the content in VR right now is like this, mapping static or 2D content into a 3D world, whether it’s watching Netflix movies in a fake home cinema, or reading The Wall Street Journal from a digital version of a New York penthouse. There’s no real benefit to looking at this content in VR, other than novelty of it all, and it seems unlikely that there’s going to be a reason to use a mobile-powered VR headset anytime soon.

Drawbacks

On top of the dearth of content and lack of utility of these headsets, they also have other problems to contend with. VR gaming seems to be a massive drain on smartphones’ battery life. The Daydream View, for example, is only compatible with Google’s own $650 Pixel smartphone, and even about 15 minutes’ worth of VR time seem to knock off about the same percentage from the phone’s battery level.

Then there’s the motion sickness. One of the main reasons why virtual reality can cause a feeling of disorientation or nausea in some people is because there is often a noticeable lag between what the person is seeing in VR and the actions the person has taken in their game, which is referred to as latency. When the lag between actions, like moving your head around in VR, is too great, it can make you feel sick. The best VR systems on the market today rely on powerful computers and fast data connections to try to reduce the latency so that users don’t get disorientated. This is more difficult to do when you’re relying on the power of a smartphone.

These headsets also have issues with immersion. I found the Daydream View to be too small for my head (perhaps I just have a massive head, who knows), such that light was seeping in from the sides and bottom, however tight I made the straps. I also had this problem with older versions of the Gear VR. The Daydream View also has an issue where you can’t adjust the focus of its lenses, meaning someone like me has to leave their glasses on to use it, which adds to the awkwardness of wearing something like this strapped to your face.

Virtual reality is likely to be at its best when its users can get lost in immersive, detailed worlds, playing games against friends halfway across the globe as if they were in the same room. Mobile headsets can’t deliver that promise, and instead try to focus on delivering moments of utility—a quick look at a 360 video; 10 minutes of gaming, for example—but even then, it’s difficult to see why it’d be worth spending about $80 to $120 on one of these headsets. I’ve argued previously that the best way to watch 360-degree videos is just on your phone, and I think after playing with the Daydream View, I’d extend that to saying that the best way to play simple mobile games is still just on your mobile. Unless you want to spend the money and time to set up a proper VR system like the HTC Vive, it might be worth holding off on picking up a VR headset like Google’s or Samsung’s.