There is a lot separating voters for and against Trump: broadly speaking, they differ based on race, gender, and education, to name a few. A deep dive into a massive dataset of tweets show they also differ in the way they talk.

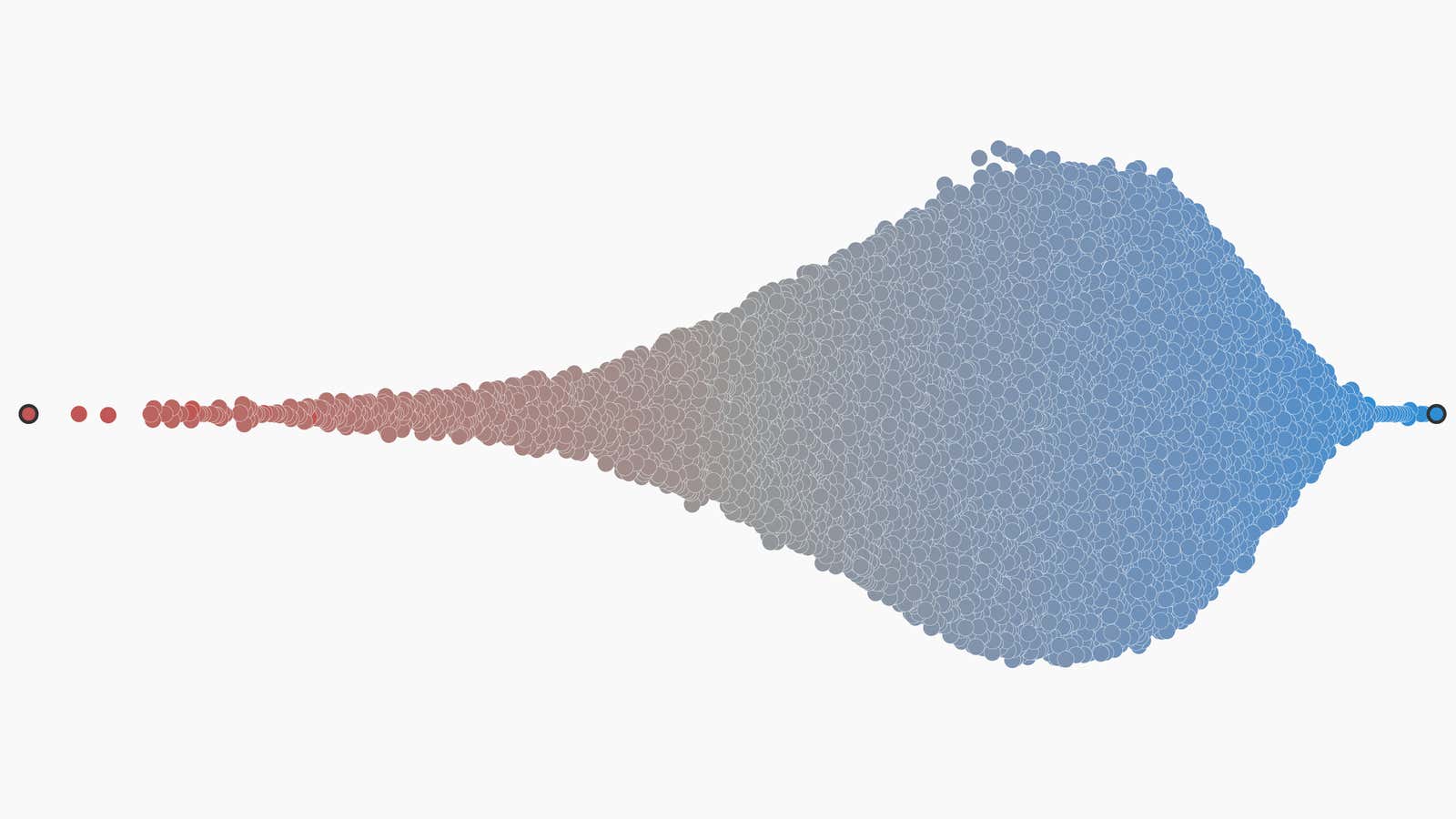

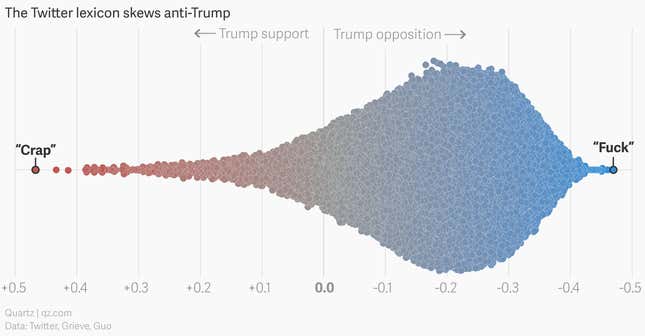

The graphic below draws on this dataset to show how well a word’s usage on Twitter corresponds to the level of Trump support in US counties. Each dot represents one of the 10,000 most-tweeted words in a collection of nearly 9 billion tweets, analyzed by Jack Grieve, a forensic linguist at Aston University in Birmingham, England.

The tweets, collected by Diansheng Guo of the University of South Carolina, span nearly all of 2014. Grieve compared geolocated tweets to Trump support for each county according to their Spearman correlation—a measure of the strength of a relationship between two variables in a dataset, commonly used in statistics. Two years old, the dataset does not reflect Twitter usage throughout the meat of the long campaign season, but it still reveals deep differences in recent language usage according to voting habits.

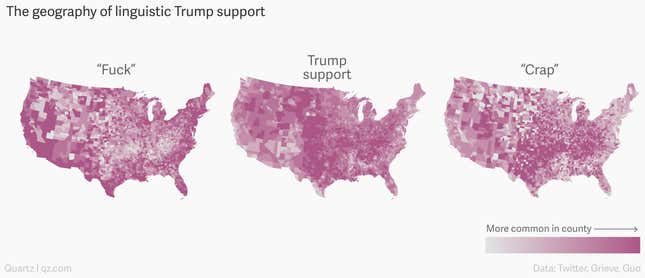

Here are three maps that help visualize the analysis: The map in the middle shows the level of Trump support in US counties; the one on the left shows the prevalence of the word ”fuck,” the most anti-Trump word in the dataset; on the right is ”crap,” the most pro-Trump word. It’s clear that the geography of “crap” is closer to that of Trump support, while “fuck” is used primarily on the coasts, where Trump support is low.

What this reveals about America

“It basically shows an urban-rural divide,” says Grieve. This division shows up in words at the extreme ends of the graphic. The pro-Trump words ”hunting,” “prayer,” and “truck” are certainly more relevant to people in rural America than in, say, New York City, where there are virtually no animals to hunt, most people are not religious, and nobody seems to own a truck. Meanwhile, the most anti-Trump words make urban Americans look like hedonists. The second-most anti-Trump word, for example, is “IPA.” Other top results are “pub,” “brewery,” “bistro,” “henny” (for Hennessy cognac), and, of all things, “brunch.” (To be fair, “whiskey” is highly correlated with Trump support.)

Then there is the un-ignorable fact that the single most- and least- Trump words are both expletives: “crap” (pro-Trump) and “fuck” (anti-Trump). We went back and forth with Grieve about these, and came up with a couple explanations. For one thing, the pro-Trump words seem to reveal a kind of rural politeness. “Gosh,” “heck,” and “freaking” are all in the the top 10 pro-Trump words, compared to the much harsher “fuck” and “fucked” for the anti-Trumps. So it’s possible that Trump support correlates with less swearing. It may also be that “fuck” has lost a considerable amount of its status as a swear word among the relatively urban Trump opposition, and is no longer as unspeakable as it once was.

The urban-rural split appears to have been a larger factor this election than in recent predecessors. The New York Times, for example, found that the number of voters per square mile correlated more strongly with vote preference this year than in 2012. Kathy Cramer, a political scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, found evidence of this divide when she traveled across rural Wisconsin to better understand politics outside of the city. “For example, people would say: Decisions are made in the cities, and we have to abide by them,” Cramer told the Washington Post.

The graphic also hints at a bias in Twitter usage. If you look at this zoomed-out picture, you’ll notice that the dots skew blue. Because this dataset normalizes word usage, this doesn’t prove that most tweets are anti-Trump. What it does show is that the most common Twitter words are usually tweeted from anti-Trump counties, so the Twitter lexicon may lean left, or urban.

Twitter offers an unprecedented dataset, or corpus, of language use in close to real-time. But is it an accurate picture of the way people talk? The words here don’t necessarily represent a holistic reflection of the American vocabulary, but in the context of this research that is more an asset than a liability. People are more likely to use colloquialisms or new terms on Twitter. “If you’re talking about everyday spoken language, Twitter is going to be closer than a news interview or a university lecture,” Grieve told Quartz for an earlier piece.

America’s cultural divisions run deep, but they may not be insurmountable. There are plenty of words in the dataset that don’t skew one way or the other, like “motivation,” “dog,” “mountains” and “leggings.” The most neutral word of all is “underwood,” but we think it might be equal parts Frank and Carrie.