As America’s Democratic Party heads into 2017, it faces an existential crisis. As a result of the 2016 US election, the party is seemingly left in tatters. Perhaps nowhere is this confusion felt more acutely than in Congress, where years of serious losses in both the Senate and House have left the party with barely a voice—and that whimper will surely diminish even further with a Republican president. Between the possible abolishment of the filibuster, as well as the Hastert Rule (an informal doctrine that blocks floor votes on bills that don’t have the support of the majority of the majority party), Congressional Democrats could be shut out of the legislative process completely.

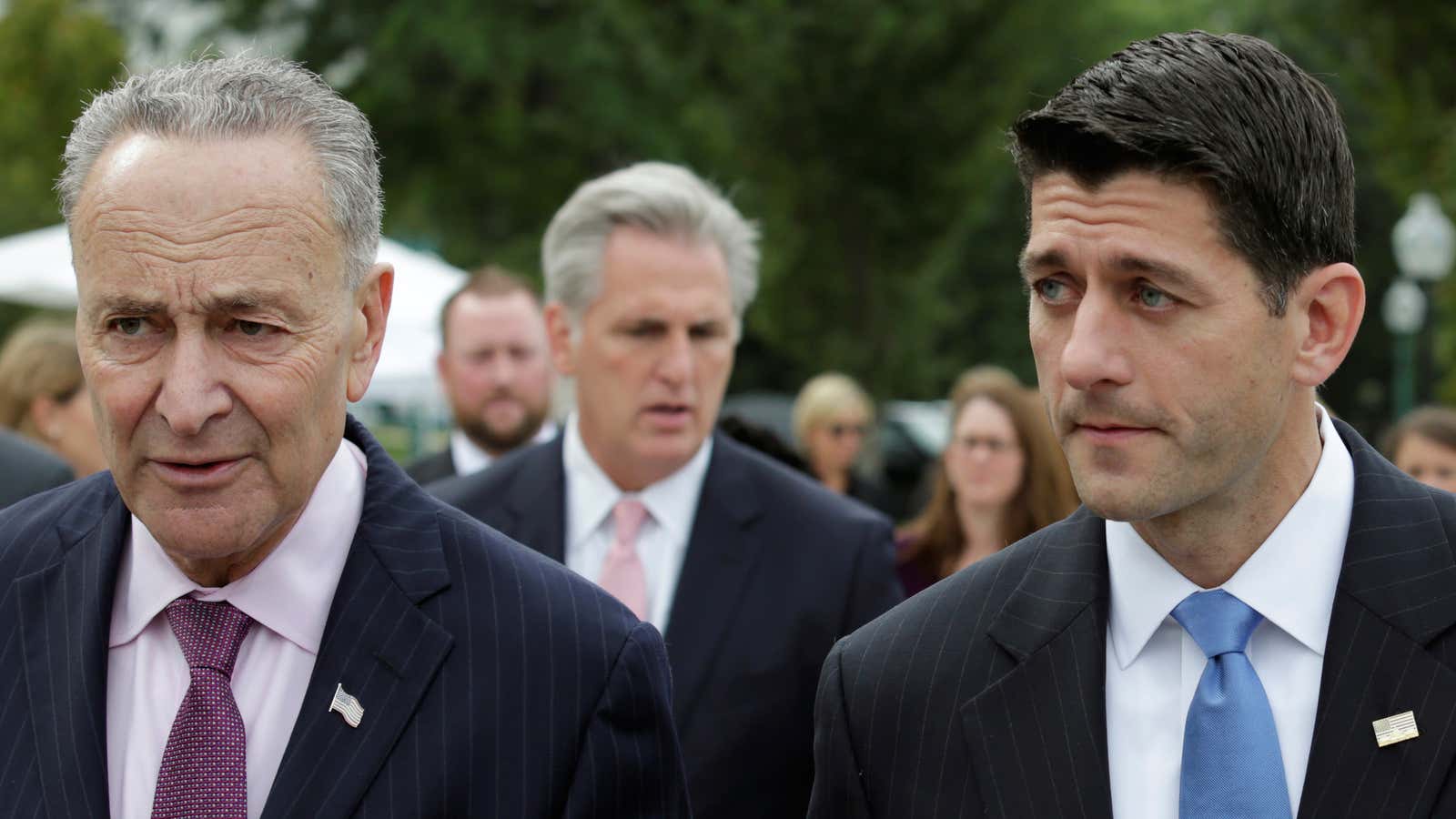

Based on past statements from Donald Trump, senate majority leader Mitch McConnell, and House speaker Paul Ryan, the GOP’s consolidation of power could lead to a decimation of Democratic strongholds. These include the repeal of all or parts of the Affordable Care Act, the privatization of Medicare, slashed taxes for the wealthy, the abandonment of Dodd-Frank financial regulations, and the appointment of conservative Supreme Court justices ready to dismantle the progressive legacy of the past few decades.

While many liberals have already begun panicking, history may offer some hope. Specifically, Master of the Senate, Robert Caro’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of former president Lyndon Baines Johnson, provides some historical guidance for a possible Democratic path to power. Like Johnson, the Democrats may be able to use ideological divisions to drive a wedge between Trump and Congressional Republicans. By making both camps look alternatively like sellouts or overly partisan obstructionists, the Democrats may still accomplish several longtime goals. Maybe.

In many ways, 1952 was similar to 2016. War-hero-turned-president Dwight Eisenhower had just been elected in a Republican wave that brought along significant, seemingly insurmountable, majorities in both houses of Congress. As Caro writes:

As the implications of the size of Eisenhower’s margin had sunk in on Democrats, along with the figures from the suburbs and even from the cities that had once been Democratic strongholds, many Democratic leaders had come to ‘privately fear that the November vote may represent a more or less permanent shift in the party balance of power.’… And even the most cursory look ahead at 1954 showed that the situation was likely to remain unchanged. A whole series of shaky Democrats are up for re-election, while only two or three Republicans need worry…. [T]he Senate will remain Republican.

A similar sentiment exists today. Republicans now hold the Senate by a 51 to 48 margin (Louisiana is in the process of a runoff for its second seat), and the House by 239 to 193. The Democrats have to defend 25 Senate seats in 2018, whereas the Republicans only have to defend 8. Heavily gerrymandered districts will also make retaking control of the House unlikely in the near future. Media headlines are already predicting that the Democrats are doomed if they don’t completely retool their agenda. Just as in 1952, “[t]he Democrats were a party in disarray, a party, as Time would put it, ‘looking for an excuse to fly to pieces,’ a party reeling and bloody amid the wreckage of a battlefield on which they had suffered a great defeat,” Caro notes.

But Johnson, the newly elected Senate minority leader in 1952, did not wallow in despair. He recognized that “while Eisenhower was popular with the voters, in the Senate it was not the Eisenhower wing of the GOP but the Taft wing (conservatives loyal to Ohio senator Robert Taft) that ruled, and with those “old guard” senators Eisenhower was not popular at all.”

Today there is a similar schism, with leaders like McConnell and Ryan representing a fairly traditional group of Republicans opposed by many within their party, including the Tea Party and vulnerable moderates. Johnson decided to position Democrats as supporters of the president, and therefore opponents of Taft Republicans. In 1954, the Democrats took back the majority in both the Senate and the House and proved Johnson’s strategy right.

Although he has triggered massive partisanship, there are a number of issues where the Democrats appear to agree with Trump and disagree with McConnell and Ryan. For example, Trump has signaled he wants a massive, trillion-dollar infrastructure plan, along with paid family leave. Trump has also backtracked somewhat on his plans to repeal the Affordable Care Act; he’s indicated he supports protecting pre-existing conditions and allowing individuals to stay on their parents’ insurance until age 26. In contrast, the “Old Guard” Republicans want to slash government spending and have voted to repeal the Affordable Care Act over 50 times. Business Insider senior editor Josh Barro has suggested these early proposals are a shot across McConnell and Ryan’s bow; an attempt by Trump to gain leverage and show the party leadership that he will not be their errand boy. While it is unlikely Trump has that kind of political foresight, Democrats can still use his support to achieve their own agenda while publicly binding Trump to proposals from which he will find it difficult to retreat.

This does not mean the Democrats should capitulate on any of their core beliefs or normalize his rhetoric—they should continue to oppose the construction of a wall with Mexico, the deportation of undocumented immigrants, and a freeze on Muslim immigration. But they also shouldn’t give up just yet.

The Republican Party’s blanket obstructionism has deadlocked Congress, and voters know this. Certainly with Trump’s unfavorable rating—not to mention the fact that he lost the popular vote—he’s no Eisenhower. But he also is arriving in the White House with stronger support in Republican areas than Mitt Romney would have had in 2012. Trump was also able to carry states that typically vote Democrat, including as Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. As a result, like Eisenhower in 1952, Caro writes, “the popularity of the man who had vanquished the Democrats could mean not doom but hope for the Democrats, that it could in fact be the very key to a Democratic resurgence.”

So when Trump inevitably suggests a proposal such as an infrastructure plan—which will be tough to find Republican support as a tool for economic stimulus—the Democrats should do as Johnson did: immediately declare their support, and force the Republicans either to agree with the Democrats or oppose a president who is, at least now, popular with rank-and-file voters. If Democrats can do this, Republicans might find, as they did in 1952, either position is a losing proposition.