The world is full of stark contrasts; and contrasts present great opportunities to spin doctors. In India, the spectre of black money—untaxed stashes of cash hoarded by individuals—coexists with the world’s highest number of people living in extreme poverty. This contrast has been there for years.

So when Indian prime minister Narendra Modi announced an immediate ban on two high-value banknotes—Rs500 (worth roughly $7.27) and Rs1,000 ($14.54)—to fight the menace of black money, as well as fake currency and terror financing, was it sound policy, or yet more spin? Or was it, as Modi’s predecessor Manmohan Singh has called it, “organised loot and legalised plunder?”

The two notes accounted for 86% of cash in an economy dominated by cash transactions. The idea behind the policy is that banning these notes will lead to more money being taxed, and those taxes will be directed to making all Indians better off.

Engulfed by crisis

When Modi announced the decommissioning of the notes, he also announced a roadmap for the future, containing 21 action points.

The prime minister rightly stressed that the benefits of eliminating these notes may not be immediately felt. He described some of the initial implementation hiccups as “temporary hardships.”

The question now is how temporary these hardships will actually be. This needs to be stressed because many of the other policies announced on Nov. 08, for example on the ability to exchange the old notes, and the ability of ATMs to dispense new notes, have not yet been met. Yet demonetisation took place with almost immediate effect.

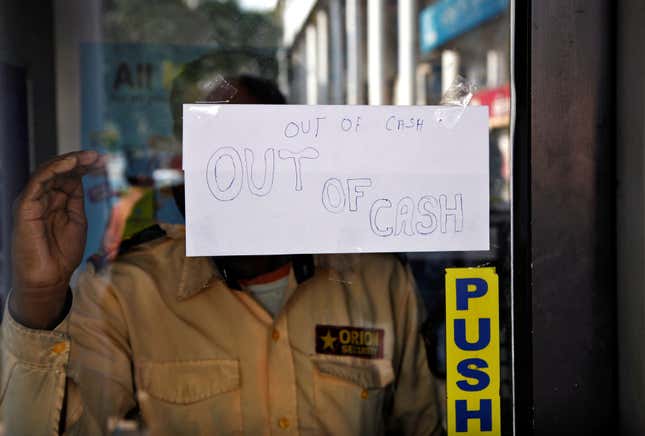

As could have been anticipated, a crisis has engulfed the nation. The degree of suffering directly relates to income, with the poorest of the poor worst affected.

Since Nov. 08, 55 people have died due to the currency chaos, never mind the suffering hundreds of millions of ordinary people, mostly among the marginalised, have been enduring.

Basic logistical issues, such as reconfiguring ATMs, or catering to rural people through cooperative banks have not been adequately planned, and at best are too little too late. The central bank is engaged in a messy fire-fighting exercise.

Do the ends justify the means?

The need for demonetising existing high-value banknotes has been investigated time and again in India and elsewhere in the world. But for fear of exactly the kind of massive disruption we are now seeing, no sudden decision was recommended for India.

In 2014, a much milder demonetisation programme was implemented, with the central bank withdrawing certain series notes from circulation gradually, giving citizens adequate time to exchange their cash, rather than cancelling notes overnight.

In opposition at the time, Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) opposed this demonetisation policy. It’s unclear why the prime minister has had such a change of heart now.

There is no doubt that the goal of the policy—fighting black money—is worthy. Collateral benefits, such as the shift towards a cashless economy, are being cited on a daily basis.

From this point of view, the ends are seen to justify the means, and Modi’s “temporary hardships” are merely the birth pangs of a new and rising India.

But are the ends really worth it? The amount of black money held in cash is tiny. Estimates vary but the range, almost always, is in single digits: from 3% to 6% or at best up to 10%, a figure mentioned in a few television debates.

So even if the policy works to eliminate black money held in cash, 90% or more of the problem will persist.

Financial inclusion

Context is important here. The demonetisation exercise has come after more than two years of a programme called Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), the “Prime Minister’s People Money Scheme” in English.

Data from the last census show that in 2011, only 67% of urban households and 54% rural households had access to mainstream financial services. Getting the remaining households access to banking services is a process known as financial inclusion.

In the context of banning bank notes, financial inclusion is crucial. People who have access to credit cards and operational bank accounts are much better prepared for a demonetisation crisis than those marginalised people whose money is all in cash, primarily in the form of these decommissioned notes.

The intent of the policy is partially to stop poor people living cash-only lives. So India needs to give people the ability to borrow money from banks when required rather than from money-lenders, a common practice among the nation’s poor.

But smartphone and internet access is yet to reach the majority of Indian households. This is not the time to talk about how online payment services can replace cash. A similar argument can be made about the proportion of people holding identity documents, a prerequisite for opening a bank account.

Social and economic divides are complex areas of study, be they investigations of extreme inequality, the education gap, the digital divide, or financial inclusion.

In general, such divides are narrowed by improving three things: affordability, accessibility, and skills. Developing skills by influencing user behaviour in many cases proves to be the most difficult and time-consuming.

Changing behaviour

To understand whether it’s possible to change user behaviour in India right now, we need to look at the household-level financial inclusion data. The best possible source is the Reserve Bank of India.

In this analysis, data on the use of bank and credit cards comes from three moments in time. The first is the latest available data, from August 2016 (pdf). The second is from January 2014 (pdf), when milder demonetisation was introduced and BJP condemned any move towards demonetisation as being “anti-poor.” The third reflects the same amount of time between the first and the second points and comes from June 2011 (pdf).

My analysis of the data from these time points shows that growth in the number of valid credit and debit cards from January 2014 to August 2016 was 85%; much higher than the 55% growth rate in the previous corresponding period.

But when it comes to transaction value, there’s a slowdown in the growth of the cashless economy. Between January 2014 and August 2016 it was 35%, down from 61% in the previous period.

All this means that PMJDY did not prepare the ground for demonetisation adequately. Indeed, many PMJDY accounts had been left unused for years. Until now, that is, when it’s being suggested that some of these PMJDY bank accounts are being misused to launder money rendered invalid by demonetisation.

This is not an unlikely scenario given how market forces operate. And surely, this is not the kind of user behaviour the government wanted to encourage.

Stop the spin

What is the right name for what has happened in India in recent weeks? Is it demonetisation, half-a-demonetisation, a surgical strike or carpet bombing? Some in leading think-tanks would identify it as poverty tax.

This is a debate for economists, academics, and policy-makers like me. But the poorest of the poor feel the pain firsthand; they do not need to debate what to call this crisis. There is no doubt that, wherever you live in the world, it’s expensive being poor. Nowhere more so than in India today.

Let’s stop the spin: demonetisation was the wrong policy at the wrong time. The economy was not ready to turn cashless, and millions of people have been left behind. As usual, it’s the poor who suffer most. Let’s hope the promised better days come sooner rather than later.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.