Martin Shkreli has been the butt of many jokes. The latest one comes from a group of high-school students in Australia.

Shkreli is the former CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, which in 2015 raised the price of the drug Daraprim by 5,000%, from $13.50 per dose to $750 (cutting it to a mere $375 for some hospitals, after an outcry). The drug treats infections from toxoplasmosis, which can be fatal in patients also suffering from AIDS. Turing was heavily criticized by politicians and even other pharmaceutical executives.

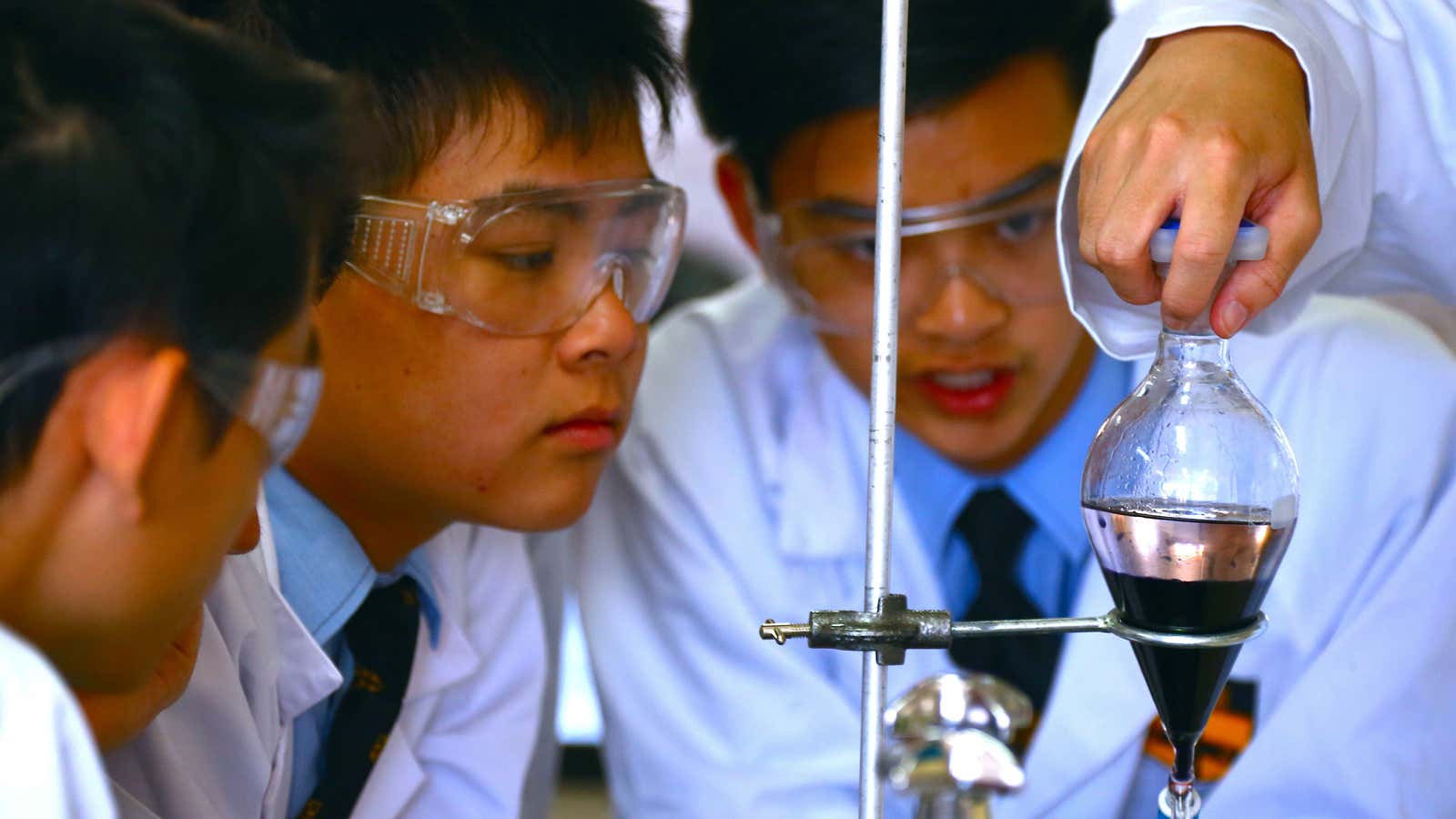

The students of Sydney Grammar School were looking for a chemistry project, and Shkreli’s antics gave them inspiration to try and synthesize pyrimethamine, the key ingredient of Daraprim, with assistance from a researcher at the University of Sydney. The end product? They calculate the cost of making the drug is $2 per dose.

When the story was reported by the Sydney Morning Herald, Shkreli responded on Twitter in his usual acerbic tone:

For the high-school kids, it was a nice science project. Sadly, barring Shkreli’s lack of nuance, he does have a point. The cost of manufacturing a drug has little if anything to do with the cost of developing it—and of marketing it, which is often higher than the cost of research. (Just as some people prefer sneakers from Nike to a no-name brand, people prefer to buy branded drugs.)

Some drugs can be discovered and developed for a few million dollars, while others might need more than a billion. On average, though, the cost has been going up. Because of these widely variable but often very high costs, the deciding factor in the price in any given country is often nothing other than what a company can get away with charging.

An extreme example is the cancer drug imatinib. In the US, its cost is $146,000 for a 1-year supply. In India, it’s only $400. That’s because in the US only Novartis, which owns the patent on the drug, is allowed to sell it. Patents are offered to pharma companies as a way of recouping the development cost of a drug. In India, after Novartis lost a court case, it also lost the patent rights to imatinib in the country. That’s why generic manufacturers, which can make the drug for about $200 for a year’s supply, are able to sell it so cheaply.

Similarly, pyrimethamine, the drug the Sydney Grammar School kids were able to make for $2 per dose, and which Turing sells for up to $750, can be bought in India for as little as $0.10.

Turing was able to charge the premium because it owned the rights to the brand name Daraprim in the US, and was its only manufacturer at the time. Turing had acquired Daraprim from another company, so it wasn’t even trying to recoup development costs—though the company says the revenue is funding its development of other drugs.

The good news is that pyrimethamine, the key ingredient of Daraprim, is not protected by patents. If a generic manufacturer can pass the US drug regulator’s tests, it can compete with Daraprim on price. Soon after Turing’s price hike, Imprimis Pharmaceuticals promised such an alternative, for $1 per capsule. But because it’s not an identical replacement to Daraprim, as of August this year, Turing was still charging many patients $375 per dose.