When you hear the name Kansas City, think art. The city is the Midwest SoHo, a capital for culture between two coasts, and a mecca for artists, where they can afford to do things like raising families (pdf, p.3). Of the estimated 6,000 artists living in Kansas City, 5,000 are gainfully employed in an artistic field. This is not just thanks to the Kansas City Art Institute or the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Arts, but because one of the world’s largest employers of visual artists is headquartered here: Hallmark.

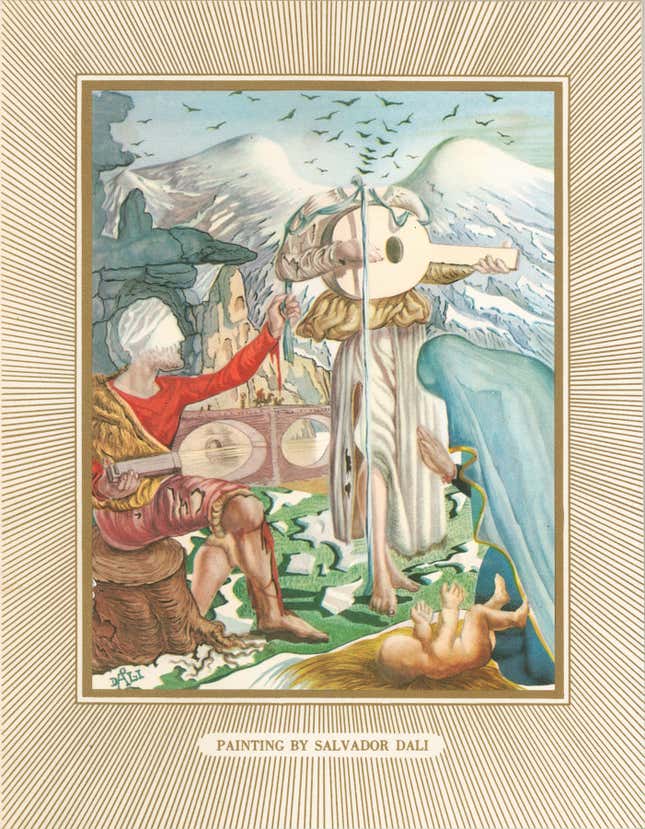

Established in 1910 by Joyce Clyde Hall—a teenager who legendarily left his native Nebraska with just two shoeboxes of postcards to sell—Hallmark is now a greeting cards and merchandise giant that employs over 1,000 artists worldwide. Five hundred of them are in Kansas City, and they have some of the world’s best art at their fingertips for inspiration; Hallmark’s headquarters also hold one of the US’s oldest corporate art collections, including Rauschenbergs, Dalìs, Picassos and Hoppers. This little-known treasure comprises 3,800 works by 1,200 artists, including some of the most important of the 20th century.

The beginning: A Christmas competition

It all started with a competition.

In 1948, Hall decided to set up a Christmas-themed art award, to encourage contemporary artists to produce Christmas themed images. Of the entries, 100 were acquired (including the winners), and were shown around the country (and the world): These were the works that established the Hallmark collection.

The award—which eventually let go of the Christmas theme—was held year after year, and grew in notoriety and profile: Edward Hopper participated, as did artists of the likes of Andrew Wyeth and Salvador Dalì. Submissions would be acquired, and end up enlarging the collection until 1960, when the final contest was held. That was not, however, the end of the collection: the Hall family, through Hallmark, continued its support to acquisitions, which were initially carried out by the architects working to design the Kansas City campus and the international offices. By 1979, the collection was large enough to warrant a full-time curator.

Interestingly, Hall wasn’t an art connoisseur, and wasn’t particularly keen on collecting contemporary art. ”Most corporate collections developed out of the interest of the CEO, like Chase Manhattan—at the time David Rockefeller was a collector— or IBM—it was Thomas Watson, the founder,” says Joe Houston, a former contemporary art curator at the Columbus Museum of Art in Ohio, who has been curating the Hallmark collection since 2008.

“J. C. Hall wasn’t a collector, but he wanted us to have [the art], the thought it was important for us to have the best in contemporary art to inspire us on a daily basis.”

Today, Hallmark’s collection isn’t anywhere near the largest—JP Morgan Chase collection counts 30,000 pieces—but its quality is remarkable. The collection’s stated goals are to build company prestige and inspire employees—particularly the hundreds of artists working to create holiday and greeting cards for the company.

At work with Calder, Lewitt and Dalì

Once you know, it’s hard to forget the art dotting the Hallmark campus. A big red Shiva by Alexander Calder marks the entrance to the Crown Center, where the Hallmark campus hosts shopping centers, hotels, and its corporate offices. Around the corner, a large Sol Lewitt wall painting takes up the hall of one of the buildings, bright and eye-catching from the outside.

Yet, the art collection seems virtually unknown to the city: Even gallery owners working downtown, in the Crossroads Art District, an area that used to host movie studios and is now teeming with art galleries and hip shops, don’t seem familiar with it. Some of the works are loaned for exhibitions, and a website was set last year to let people browse the collection, but for the most part, the art is intended for employees’ eyes only.

The main building slopes downward on the side of a hill, with the main entrance on top at the eighth floor and the visitor center on the bottom at the first floor. The building, which once also served as the cards production facility, has mostly low ceilings, and the sheer amount of art of display easily turns hallway into the well-stocked walls of a gallery.

On one wall, a 1959 oil by David Park depicting three young boys after a swim hangs next to a 2008 painted bronze sculpture by Tony Matelli. A short walk away, one of Benjamin Edward’s largest paintings, a 2002 layered vision of urban Los Angeles, hangs behind a 1987 Nancy Dwyer sculpture that spells out the word “dog.” Down a flight of stairs, by an elevator, a 2010 diorama by Patrick Jacobs set in the wall shows a view of Brooklyn from the artist’s studio.

A large 1992 photograph by artist Barbara Kruger reminds the watcher, A picture is worth more than a thousand words.

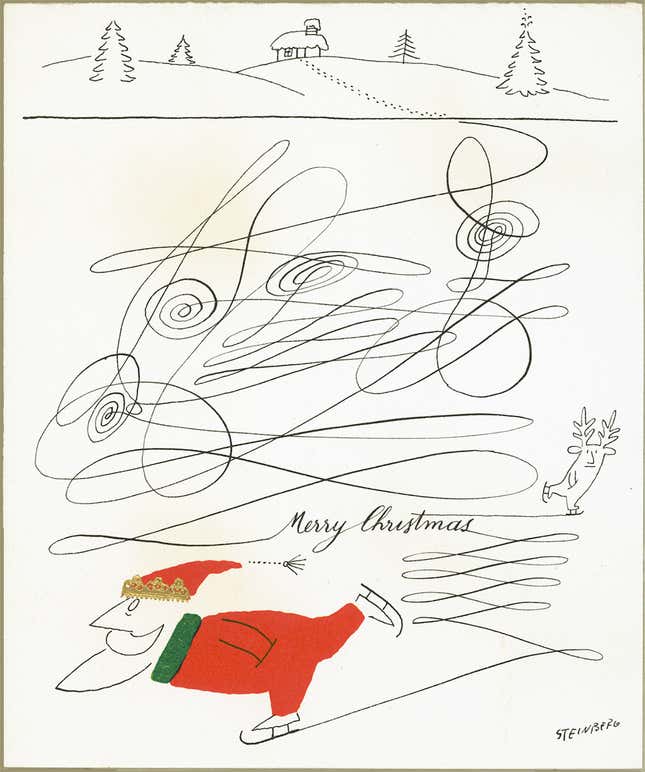

And behind all of it is the vault. The works rotate yearly, and many are kept in storage when they are not being displayed. These include works by Norman Rockwell, Saul Steinberg, and Roy Lichtenstein.

Creatives standing on the shoulders of giants

“When I walk in, I walk past Deborah Butterfield, I walk past Pablo Picasso, I walk past Saul Steinberg, Norman Rockwell, Haddon Sundblom, Herbert Ferber,” says Ken Sheldon, who has been working as an artist at Hallmark for over twenty years. “I walk past these artists and if they hadn’t been part of my education, they became part of my daily life.”

That is, in a nutshell, the main aim of this high profile collection, and one that sets it aside from similar ones owned by banks or insurance companies. “We are a creative organization, so I believe we live with the art a bit differently on a daily basis,” explains Houston. He claims the collection grows as a museum’s would, prioritizing the artistic value of acquisitions over investment value.

Artists are constantly inspired by the collection. Melissa Powlas, who works on creative trends forecast for Hallmark, says that she recently saw at a trade show that 1950s and 1970s influences would be popular next year. So she went back to Hallmark HQ to consult the collection’s pieces from those decades, to nail down the colors that artists preferred at that time.

For Sheldon, the inspiration is more in the techniques. “Sometimes I need to run to these heroes,” he says, especially when “trying to figure something out, and go look at somebody who really figured it out really well.” For that, he and other creatives reach out to the curator, who may dig into the vault and bring out exactly what they need.

Recently, says Sheldon, he was looking for help with watercolor, so “I talked to Joe [Houston] and he went down [to the vault] and he brought out a whole bunch of Rockwell watercolors.”

This is more than a perk for the artist employees of Hallmark. According to Darren Abbott, the creative vice president of the company, running a creative business requires providing an environment that’s constantly inspiring. ”You can’t just push a button and be creative,” he says.

But the relationship works the other way, too: It’s not just the collection that inspires the artists, it’s the day-to-day creative work that helps curators decide what direction the collection should take. Looking at the creative work being done at Hallmark “helps me see what may be the priority for acquiring for the collection,” says Houston, who has been looking more into op-art and mid-century modern design after observing company artists’ interest.

After all, even Norman Rockwell was once a Hallmark artist. So was Dalì. And so was Winston Churchill: They were the first of a series of high-profile artist collaborations that started in the 1940s and continued through the decades, involving visual artists as well as writers such as Maya Angelou, who authored messages for an entire collection of greetings and objects in 2002. These artists’ cards have since transcended the drug-store business model—and are now preserved as part of the company’s private collection.