A curious thing happens to medical students shortly after they enter clinical training. As explained in an evocative essay in the New York Times, the students begin to stop trusting their own ability to examine a patient. They instead start to lean on the machines that create medical imagery—MRIs, CT scans, ultrasounds—to do the work of “seeing” for them. These and other diagnostic tools are so good at what they do that young doctors may not feel pressured to develop their own powers of observation.

That’s a shame, say the previous generations of doctors that act as their mentors, because it means the young docs can miss less-obvious clues in a patient, or the patient’s environment, that could point to obscure or even common health conditions, or teach them something useful about a patient’s lifestyle or mental state.

To encourage students to build a habit of thorough visual inspections, Yale professor and dermatologist Irwin Braverman, and Linda Friedlaender, curator of education at the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA), co-pioneered a novel program in 1999 that introduced medical students to Victorian and Pre-Victorian art. Variations of the program caught on across the country and are now in place at more than 70 institutions.

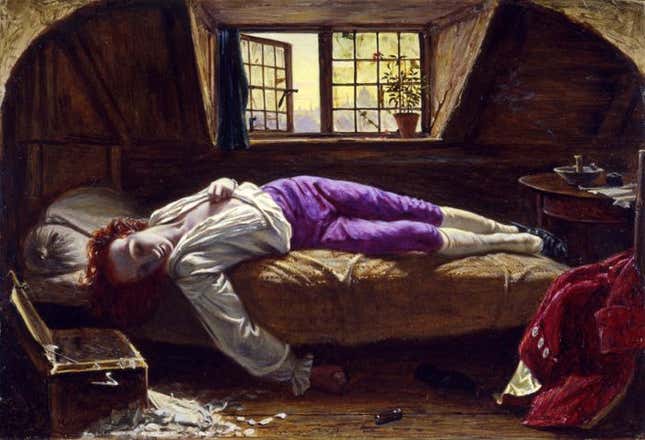

At Yale, Friedlaender explains, students are divided in groups of four and assigned to a moderator. Each one takes a turn with a selected painting, sitting in front of it for 12-15 minutes, perhaps with a notepad or sketchbook, to jot down their impressions. They are then asked to describe the painting to their peers in as much detail as possible. (All the paintings are representational.)

In the first half of the subsequent discussion, the students are required to supply only an objective description of the painting; they are not allowed to interpret, draw conclusions or offer an opinion. Making judgements is usually their first instinct, however. “A student will say ‘This painting is of a sad woman,’ and we’ll say, ‘That’s an opinion. Tell us more about what you see in her,'” says Friedlaender. They’re taught to note things like a furrowed brow or a lowered chin, hand gestures, posture, and clothing, and all the objects and environmental details, even those in the edges of a painting.

Then comes the second half of the discussion: “Once we are satisfied that they’ve given a complete visual inventory of the painting, they are allowed to draw conclusions about the narrative,” Friedlaender says. That’s when another student might jump in with a different interpretation. “We talk about how we’re looking at the same object, i.e., the same patient, and people are coming up with different conclusions,” says Friedlaender. The same thing can happen with a patient who presents with symptoms that don’t neatly point at an obvious diagnosis. It may look like pneumonia, for instance, but it might be something completely different—or maybe the patient has pneumonia and another illness.

The moderator will then try to move on to the next artwork, but often the medical students, being medical students, will insist on knowing who got the “right” answer. Only then does the expert share what’s known about the painting—whose title and label is covered—but the research behind a piece is introduced as just more evidence to consider, not the final word. The lesson: In art, there is ambiguity, just as there is in medicine. “Sometimes I say, ‘I don’t have the information to tell you which conclusion makes the most sense,’” Friedlaender says.

All the gazing and art discussion apparently works. A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2001 showed that students who had taken the Yale art class were 10% better at recognizing symptoms in photographs of patients. A later study of a nine-week Harvard program, published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, found that graduates of the art class made 38% more visual observations during an exam than a control group that prepared for the same test with only a lecture.

Writing in the Journal of the American Medical Association study, Braverman explained that the art classes jump-start “the experiential process” so that students build their talent for gathering and reassembling observed data logically. “That is the skill of the diagnostician and our favorite Sherlockian detectives,” he wrote.

These are some of the YCBA paintings used to train the students become better visual analysts: