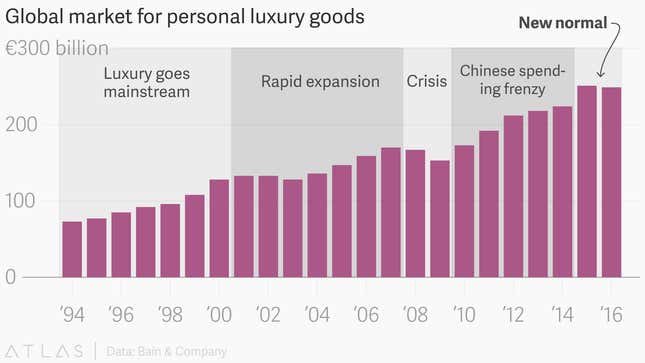

Last year was a bad one for many companies selling expensive fashion, handbags, and jewelry. For the first time since the financial crisis of 2008, the global market for personal luxury goods failed to grow, stalling at €249 billion (about $258 billion).

The good news is that 2017 should see a return to growth, according to a Dec. 28 report on the global luxury market by management consulting firm Bain & Company, only it won’t look anything like the boom years from 2010 to 2015, when global sales of such goods jumped 45%, fueled by Chinese consumers with high-end appetites. The slowing of China’s economy and its government’s ongoing crackdown on corruption, paired with turmoil in the US and Europe from Brexit, terrorism, and the US presidential election, have created a “new normal” of low single-digit growth and intense competition. The years ahead will produce ”clear winners and losers,” Bain says, determined by which brands can read the field and respond best.

China is at the center of this shift. Today Chinese shoppers account for 30% of all sales of personal luxury goods. While Bain foresees the Chinese market improving again after contracting slightly in 2016, it isn’t likely to return to its former rate of expansion, which insulated brands’ bottom lines from other problems. “We expect around 30 million new customers in the next five years coming from the Chinese middle class,” Claudia D’Arpizio, a Bain partner and lead luxury analyst, told Quartz in an interview last year. “But this is nothing comparable to the past big waves of demographics entering [the market]. This new normality will mean mainly trying to grow organically in the same consumer base, being more innovative with product, more innovative with communication.”

Exane BNP Paribas echoed the thought in a December research note to clients. “The peak of the largest nationality wave ever to benefit luxury goods is behind us,” the authors wrote. “Brands need a new paradigm, other than opening more stores in China and bumping up prices.”

The period luxury is entering could see some of its slowest growth since it started opening up to a mass audience around 1994. That was the year, D’Arpizio noted, that “the jeweler of kings and queens,” Cartier, launched its first lower-priced line for mainstream consumers. Other brands followed in search of greater sales, and names “like Gucci, Prada, also Bulgari were really growing, doubling size every year, sometimes triple-digit growth rates, opening up to 60 stores every year and covering all the capitals across the globe,” she said.

Around 2001 came another period of expansion when brands became global retailers, not just selling wholesale, amid a spate of acquisitions that would eventually create today’s giant luxury conglomerates, including LVMH and Kering (previously Gucci Group). By the time of the financial crisis, luxury had conquered much of the US, Europe, and Japan, and then China came along to offer more unfettered growth.

There’s no new China, however, at least not now. The next big luxury market is likely Africa, particularly countries such as Congo, Angola, and South Africa. But D’Arpizio estimated this scenario won’t come about for seven to 10 years, meaning only moderate expansion for some time.

“In the new normal, we expect a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3% to 4% for the luxury goods market through 2020, to approximately €280 billion,” Bain’s report says. “That is significantly slower than the rapid expansion from the mid-1990s to the late 2000s.”

Other characteristics of this new period include more shoppers making purchases at home. Last year, local purchases exceeded tourist purchases by five percentage points, the first time since 2001 that has happened.

And digital sales will keep growing. Last year they accounted for 8% of the industry.