In the new year, many of us resolve to cook more often—a habit that’s healthier, cheaper, and often more enjoyable than eating out or ordering Seamless. Yet it can be hard to find the time to devote to meal preparation, much less creative menu-planning.

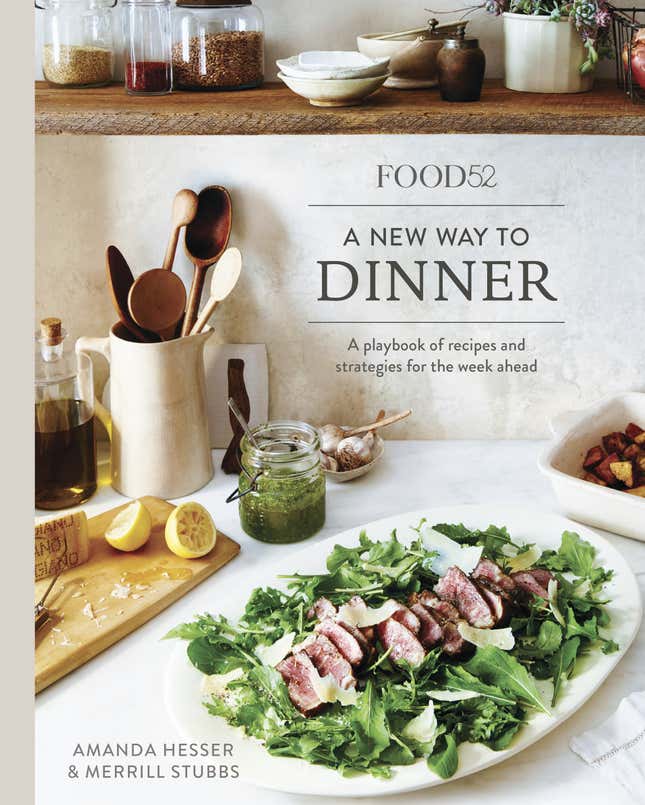

It’s little wonder, then, that meal kits like Blue Apron—which offer pre-planned menus, detailed instructions, and tiny plastic cups of pre-portioned garnishes—can barely keep up with demand. But for those of us who prefer a more wholesome (and less expensive) approach to streamlining our time in the kitchen, there’s A New Way to Dinner—a new book by Amanda Hesser and Merrill Stubbs, founders of the beloved food media company Food52.

Like Blue Apron, the cooking system designed by Hesser and Stubbs aims to simplify the process of grocery shopping, menu-planning, and cooking. But rather than compelling cooks to whip up a whole new dish every day or two, the book advises readers to invest a few hours of weekend kitchen time to create meal components to be mixed and matched throughout the week. This strategy reflects how its authors—both mothers of young children—adapted their cooking habits for a hectic phase of life.

“As our business took off and as our families grew, we were facing new time constraints,” says Hesser. The entrepreneurs realized that if they needed a new system for cooking, many other busy people probably felt the same way.

“Getting in the kitchen is not the hard part,” says Stubbs. “It’s deciding what you’re going to make, what your dinners are going to look like over the course of a week, getting your grocery list together, and then doing all the prep in an organized way…we wanted to clear the path.”

It’s not a cookbook; it’s a way of life

A New Way to Dinner is delivered in the guise of a cookbook, but has some qualities of a self-help book: a friendly introduction warning readers the book may seem daunting, a promise that the benefits of this new lifestyle far outweigh the challenges, and chapters of recipes divided by a week’s worth of cooking, rather than sections such as “main dishes,” and “salads.” Each of the seasonal plans contains a week’s worth of menus (five dinners plus a handful of lunches), a clearly laid-out cooking plan, a shopping list, and a series of recipes.

To understand how the system works, look no further than Hesser’s meals this week. Over the weekend, she prepared a pot of brothy, garlicky white beans and a pan of oven-fried chicken. These became the foundations for a week’s worth of lunches and dinners that included chicken and latkes, beans with thick parmesan shavings for the kids, a thinned-out white bean soup, and a Burmese chicken salad with fried shallots and fish sauce.

“The whole goal is to make your time in the kitchen well spent,” says Stubbs. If you’re chopping onions, you’re only doing it once.

A test run

The book is divided into four seasons, each of which has four weeklong plans—two by Stubbs, and two by Hesser. To try it myself, I started with one for “Merrill’s Fall.”

As promised, I indeed felt daunted when I turned to the “game plan” page, which said I would be ”hunkered down in the kitchen for about three hours.” But a week of meals including baked penne with sausage ragù, roasted applesauce, and warm chicken salad—and more!—sounded worth it.

The grocery list was helpfully sectioned into categories such as “produce,” “baking aisle,” and “spices,” which allowed me to easily check my cupboards for items I might already have and efficiently divide my shopping between the farmer’s market and grocery store.

Once home with my ingredients, I cleared my kitchen counter, and followed Stubbs’ instructions with hopeful zeal. One of the book’s most helpful aspects is the way its authors—both of whom learned to maximize their time in professional kitchens—coordinate your multi-tasking, specifying the order in which to prep ingredients, how best to store leftovers, and so on. Before long, I had roasted apples cooling on the counter, sausage ragù bubbling on the stove, a pan full of chicken with rosé, tomatoes, and garlic roasting in the oven, and a refrigerator stocked with clean, dry salad greens.

That night, and for about 12 days to follow, I used every Tupperware in my possession and ate like a queen—a smug, healthy queen who popped a sweet potato into the oven while she showered after the gym, spooned reheated ragù over the top, and had salad on the side. For work, I packed lunches of chicken over greens with jars of red wine vinaigrette. When an unexpected potluck arose, I had a pan—literally, a pan—of baked penné with sausage ragù to contribute. I didn’t buy groceries for two weeks. When a friend arrived on a late night flight, I poured her a glass of rosé leftover from the chicken recipe, and made her a grilled cheese with a side of homemade apple sauce. No sweat.

Make it work for you

While the book is structured for a family of four, I was cooking only for myself in a tiny kitchen, so was happy to see a section entitled “to scale back.” This gave me license to skip baked pasta and polenta, and instead serve the ragù over pasta one night and baked sweet potatoes another, and to opt for store-bought applesauce over the homemade variety. That said, in the end, the farmer’s market apples looked so good, I made the applesauce anyway.

But I skipped using it for an applesauce cake included in the week’s menus. Instead, I ate it as a side dish and stirred it through yogurt for morning snacks. I also skipped a recipe for zucchini with chile and mint. I just had so much food already.

The authors emphasize their system is designed for this sort of flexibility.

“It’s about teaching skills that can be applied and adapted to your own taste,” says Stubbs. But there is one thing that’s non-negotiable, according to Hesser. “Wash dishes as you go,” she says. “No one wants to end a cooking session with a huge pile of dishes.”