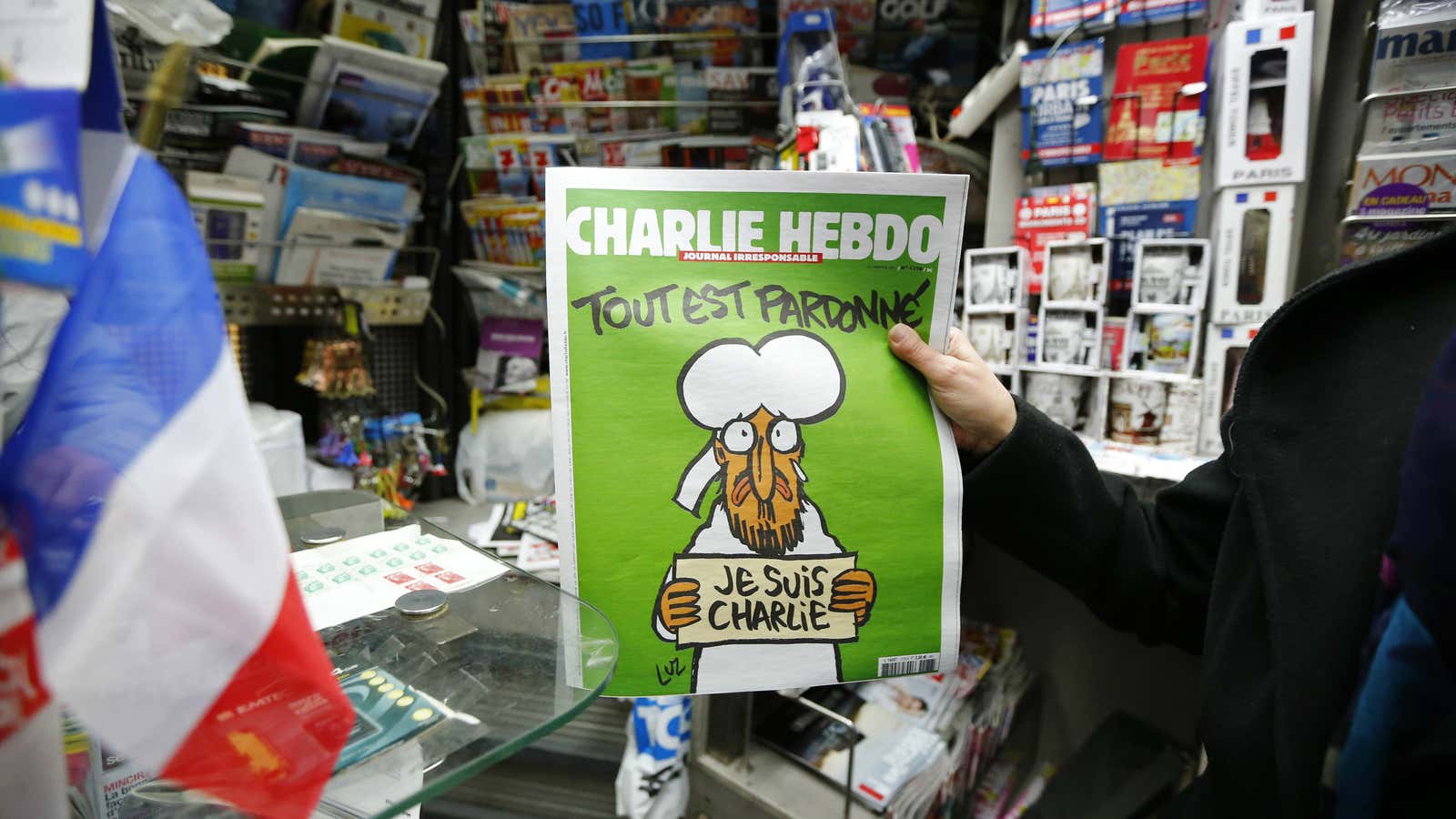

On Jan. 7, 2015, two gunmen stormed Charlie Hebdo’s office in the center of Paris, massacring 12 and wounding five. The French satirical magazine had been printing cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad, an act that is deemed blasphemous in Islamic culture. After the attack, the world rallied together to show solidarity for the magazine’s actions: “Je suis Charlie,” we said in unison.

But the magazine’s legacy unfortunately appears to be in limbo.

After the 2015 attack, Charlie Hebdo became a firebrand of sorts; it looked like their commitment to free speech was triumphing over the naysayers. In the immediate aftermath of the attacks, 3.7 million demonstrators—including notable world leaders such as then-British prime minister David Cameron, German chancellor Angela Merkel, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu—took to the streets. The cash-starved publication witnessed glory days as purchases of their successive issue logged nearly 8 million sales, many of which were bought as an act of solidarity with the magazine’s values.

However, the fervor was short-lived. Over time, the fine moral line Charlie Hebdo treads between voicing dissent and printing out-right insults has blurred, leading to some parties to call for its censorship. For example, University of Manchester and University of Bristol in the UK have blacklisted Charlie Hebdo, the latter on the grounds of violating the institution’s “safe space” policy with its offensive content. The magazine’s brutal satirical representations of the death of three-year-old Syrian refugee Aylan Kurdi in 2015 and again in January 2016 sparked outrage. And its cartoon commentary on the victims of last September’s Amatrice earthquake in Italy, which illustrated the victims as pieces of pasta, led not only to outcry at their poor taste, but to the Italian town suing Charlie Hebdo.

The shifting status quo is apparent within the magazine’s internal ranks, too. In July 2016, the magazine’s editor, Laurent “Riss” Sourisseau, announced they would no longer draw Muhammad, saying they’ve “defended the right to caricature” already. In September 2015, well-known cartoonist Renald “Luz” Luzier and columnist Patrick Pelloux left the magazine, unhappy with its new policies and character. Those unhappy with the post-attack management also called the newfound wealth the “poison of the millions.”

A day before the second anniversary of the tragic event, journalist Zineb El Rahzoui also formally quit the publication. (However, she had “not written a line” for them for a year, and had originally announced her plans to leave in September.) A lightning rod in French media, El Rhazoui alleged that Charlie Hebdo was bowing to pressure from Islamic extremists by steering clear of drawing Prophet Muhammad. “Freedom at any cost is what I loved about Charlie Hebdo, where I worked through great adversity,” she said.

But it’s not all bad news. In November 2016, the magazine took its contemptuous brand of journalism to Germany, selling copies of German translations of its French content for €4 ($4.21). By December, they released the first German-based edition with a torn-down Merkel gracing the cover. The 16-page-issue, created by Riss, depicted thoughts from German locals on cultural heritage, national identity, and the refugee crisis.

As the world grapples with more austerity and conflict in the coming months and years, whether Charlie Hebdo rides the wave of criticism or goes under could redefine political satire.