If you grew up in the English-speaking world in the 1970s or 1980s, you probably encountered the Berenstain Bears, the much-loved children’s book series by the American husband-and-wife team Stan and Jan Berenstain.

Beginning with 1962’s The Big Honey Hunt, the Bear family—Papa, Mama, Brother, Sister, and later baby Honey—navigated with love and folksy wisdom the changes and obstacles common to Western childhoods: new babies, new schools, dentists, messy rooms, sibling rivalry. The world beyond Bear Country may have changed drastically in the last 55 years, but the Bears never do(at least until 2008, when family became evangelical Christians under the stewardship of Stan and Jan’s son Mike Berenstain).

“The Berenstain Bears are always facing up to new challenges, but their lives—in that big tree house down the sunny dirt road—never change much,” wrote journalist Saul Austerlitz in the New York Times Magazine. “Parents know best, children always heed their lessons and everything is in its right place.”

Bear Country’s comforting consistency may be reassuring to children. But to an adult re-reading the books today, it’s clear the Bear most resistant to change is Papa.

He undermines Mama Bear’s efforts to get the family eating healthy in the Berenstain Bears and Too Much Junk Food. When a family of pandas moves in next door with their unfamiliar food and culture in the Berenstain Bears’ New Neighbors, he’s a downright xenophobe. (Disclosure: I have two small kids and so have read and thought more about the Bear family dynamics in recent years than a normal adult should.)

Nowhere is this anxiety more evident than in the Berenstain Bears and Mama’s New Job. After nearly choking on his soup when Mama announces she’s opening a quilt shop, Papa Bear’s first worry is that a job will leave Mama less time to scavenge worms for his fishing. Yes, that’s a whole lot of gender politics to read into a family of cartoon bears. But the book also reflects a broader (and still ongoing) cultural conversation about families and work.

A working mom—at least the human kind—wasn’t a novelty when the book came out in 1984: Nearly 60% of US women with children under the age of 18 then held jobs outside the home. Of course many families then (as now) were grappling with what women’s return to the workforce meant for domestic roles, and upon whose shoulders the task of balancing work and life must fall.

Mama’s New Job came out while sociologist Arlie Hochschild was researching her groundbreaking 1989 book The Second Shift, which documented the tensions in American households as gender parity in the home failed to keep pace with women’s increasing responsibilities outside it. Hochschild called this the “stalled revolution.”

In the 1981 book What’s Happening to the American Family?, economists Sar A. Levitan and Richard S. Belous wrote that the American family had some major changes to adjust to. “The greatest changes will be the reallocation of work responsibilities within households,” they wrote. “These changes—unlike fads which come and go—will probably have some of the deepest and most lasting effects on the family institution and on American society.”

The strong reactions this book provokes, even decades after its release, hint that we’re not entirely settled into that new phase yet. “Mama Bear now works late and comes home well after dinner and instead of the family eating healthy meals—they now pick up burgers and fries while Mama Bear waves around cash. Really?” a one-star reviewer on Amazon complained in 2012. “She no longer has time to spend quality time with the cubs.”

So, how did the Bear family take on the problem that has no name? Take a look and decide for yourself.

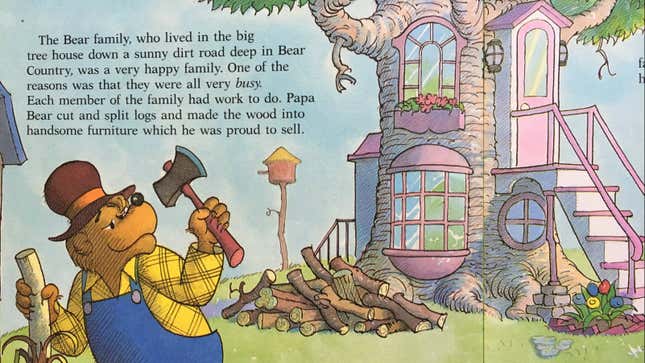

This is the Bear family. They live in Bear Country. All the Bears have important jobs to do.

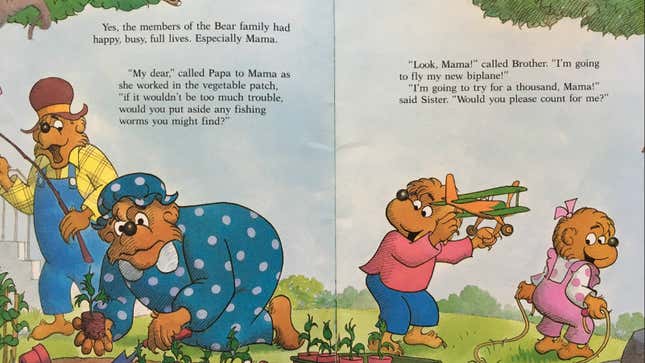

Mama Bear has the most important job of all. In addition to caring for the treehouse and garden, she also has to validate all the other Bears’ experiences. What a lot of unpaid labor!

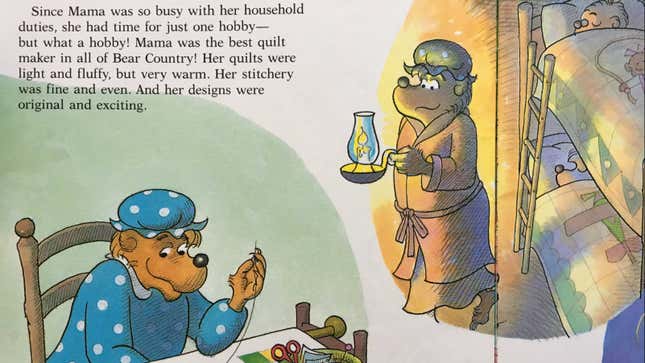

When she isn’t taking care of her treehouse or her family, Mama likes quilting. Quilting is fun. Quilting is therapeutic. Quilting disguises subversive political messages as harmless sows’ work.

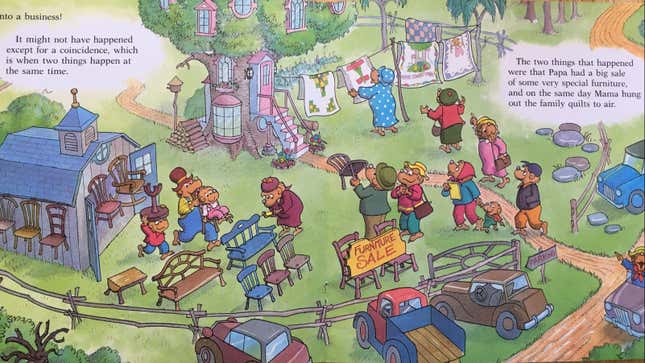

Everything changes when Mama puts her handmade quilts out to display—sorry, air—on what just so happens to be the day of Papa’s furniture sale. That’s a coincidence. (Is it, though?)

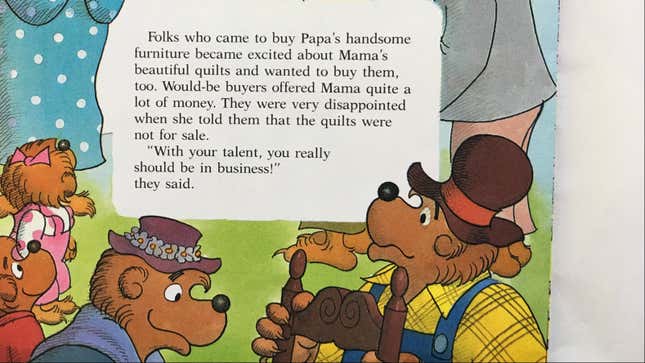

People love Mama’s quilts. They want to give her money for them. Papa last had this expression in Berenstain Bears and The Ghost of the Forest. A lady bear’s economic autonomy is as scary as the undead.

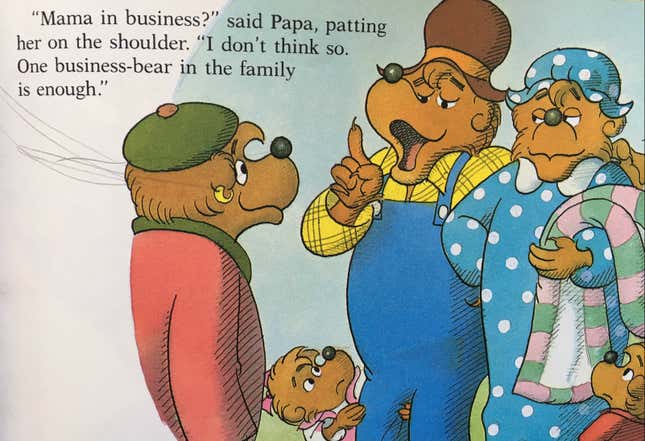

“One business-bear in the family is enough,” says Papa. Even the cubs think this is bullshit.

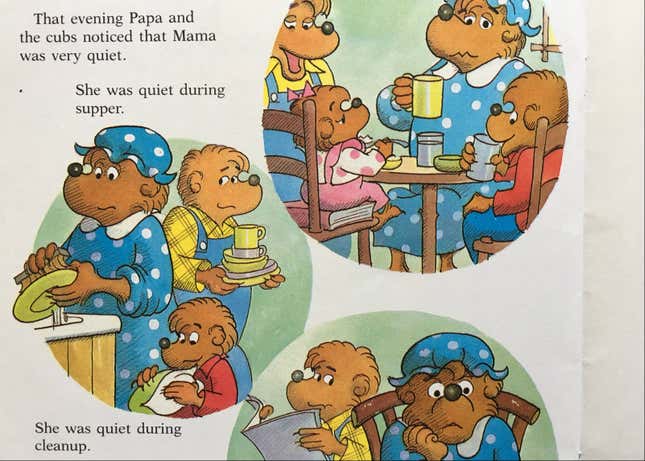

At home, Mama is quiet. All the Bears get nervous when Mama is quiet.

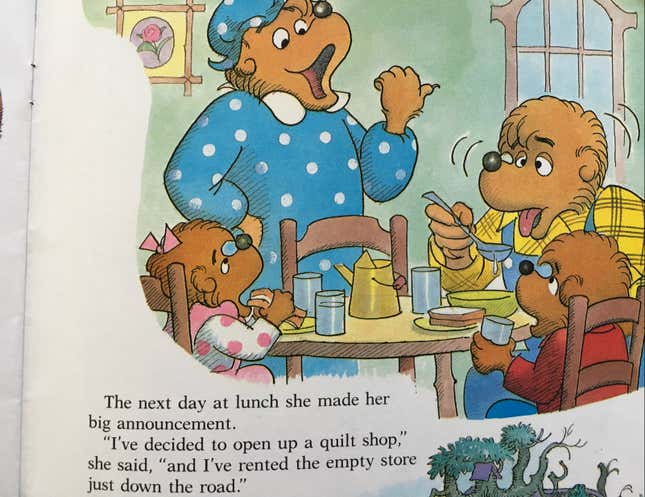

Mama is going to open her own quilt store! Papa is going to throw up that soup.

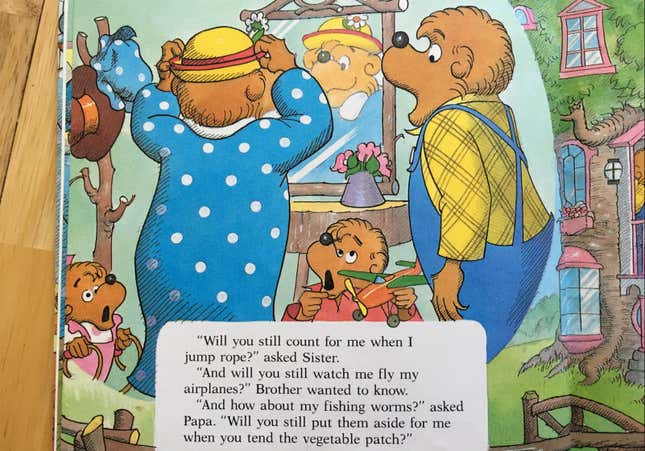

Brother wants to know how this will affect his model planes. Sister is worried about her jump rope. Papa is worried about his worms. Brother and Sister are children. They are naturally egocentric and wary of change. What is Papa’s problem?

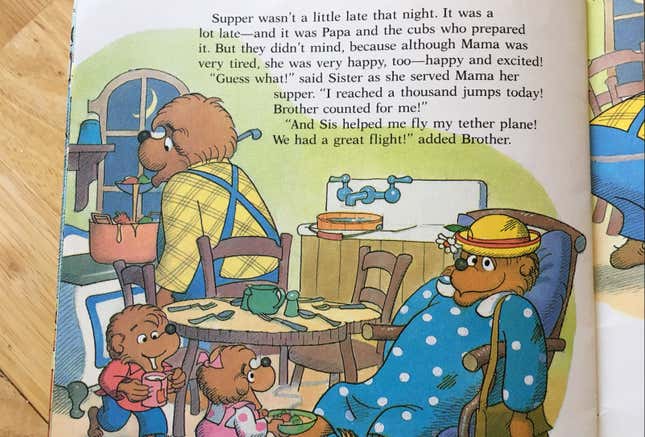

Mama’s home from her first day at work, and the Bears are so happy to see her and tell her about everything she missed. No one even minds that dinner is late and they had to prepare it themselves. They’re not upset at all. Just mentioning it!

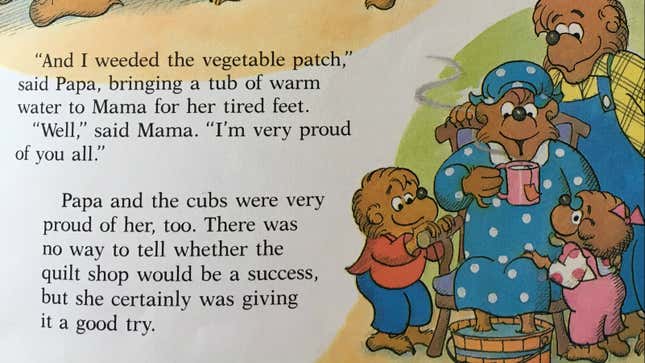

Everyone is proud—of Mama for launching a sow-owned enterprise and of Papa, for doing a chore by himself. It doesn’t matter if the quilt shop succeeds or not. All that matters is that Mama tries hard, has fun, and doesn’t threaten anyone’s sense of identity as the household’s main provider.

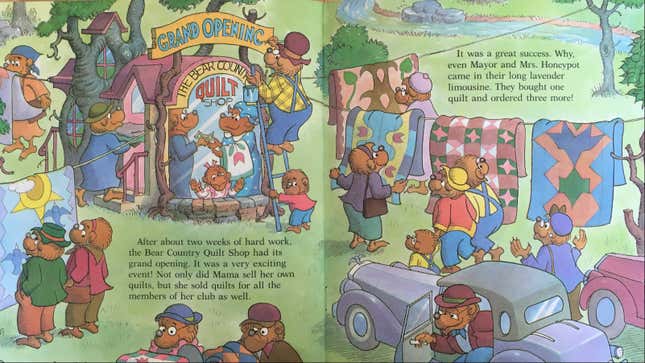

The grand opening is very exciting. It’s so exciting that no one thinks to ask where Mama got the start-up capital. Maybe Mama has an account at Bear Country Mutual that nobody knows about. Maybe Papa just thinks he’s been supporting a family through occasional sales of custom birch furniture all this time.

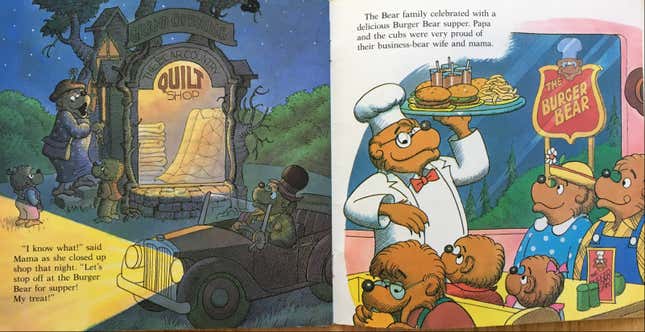

In the end, having a business-bear for a mom isn’t so bad. Burgers!