In August 2014, Roxane Gay released a series of essays called Bad Feminist. It debuted as a New York Times paperback nonfiction bestseller and spent another seven weeks in total on the list. When Gay had negotiated her advance, Harper Perennial paid her only $15,000. That’s about a third of what a first-year banking analyst with an MBA makes as a signing bonus.

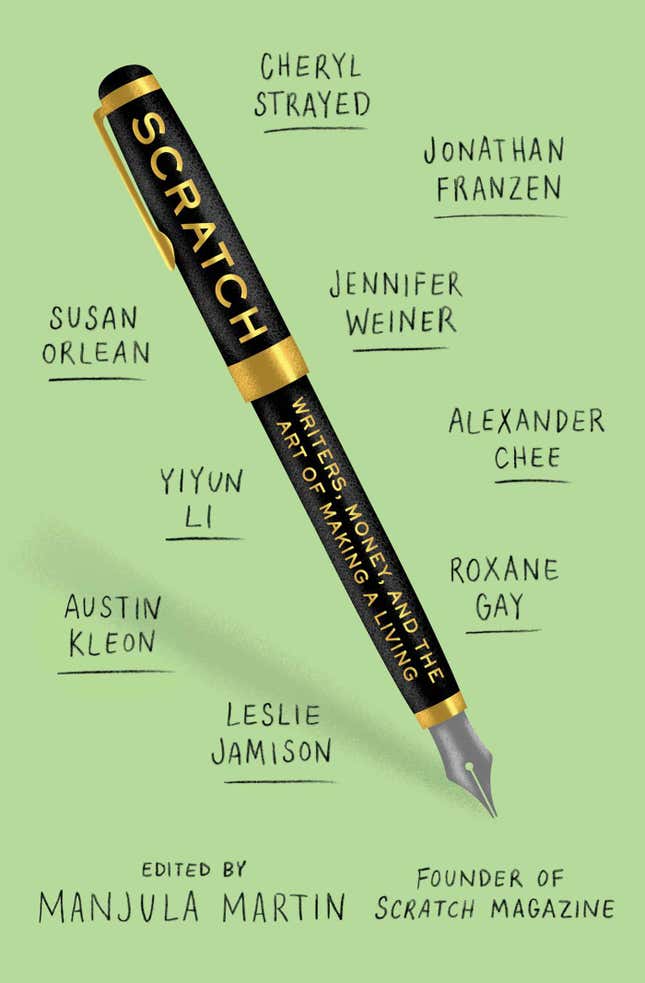

Scratch: Writers, Money, and the Art of Making a Living is a new book edited by Manjula Martin, and it reveals the often depressing, poignant, hair-tearing, compromising positions that writers take to pay their rent. The book contains interviews between Martin and big-name authors like Cheryl Strayed and Jonathan Franzen, as well as essays from Kiese Laymon, Mallory Ortberg, and Emily Gould. Scratch was released Jan. 3 from Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

The book comes at its subject from a slew of voices and angles, which include moments of social anxiety at publishing galas, an FAQ on how to buy a home, and what it means to be a “real black writer.” For aspiring MFAs, the collection serves as a warning of the slog to come, and for book lovers a reminder of the realities of creative life. But what’s likely to draw in anyone who picks up the book is the punch-to-the-gut realization that some of your favorite books were born out of debt.

Strayed, the author of Wild, says she thought her life would change forever when she signed a $100,000 advance for her first novel in 2003 (about $130,000 today). Upon receiving the first of four installments, Strayed realized that the $21,000 (after her agent’s cut) would be immediately spent: She used it toward her $50,000 credit card debt. Gay sold her first book for a $12,500 advance, and her second for just $15,000. Only by her third book did she get a $75,000 advance.

Despite the sentimental image we have of an introverted auteur squirreled away in her apartment with don’t-give-a-fuck, what-is-Twitter-anyway armor, making a living from writing is deeply unsexy, and even unseemly. The illusion of creative freedom exists even among writers, who don’t divulge to writer friends how much they make, how much they’re struggling, or what it really takes to keep writing. Aside from the lucky few with trust funds, few writers talk about the help they do get, like in-laws who can watch the kids or help pay college tuition, says Strayed.

Gay is extremely prolific and was able to rack up a salary of $150,000 in 2014, but mostly from teaching and speaking fees. Franzen, who says he sold his first book for $20,000 in 1988 (about $40,000 today), recalls drinking jug wine and living off food from book parties. Sari Botton, editor of the 2013 essay series Goodbye to All That, has a juicy chapter about her career as a ghost writer. She recounts contract after fallen-through contract: wedding-planner book proposals, flopped memoirs about disabled sons, and repellent pseudo-celebrities.

Through each essay, we learn a truth about living from what you love. The marginalia are filled with false hopes, and the footnotes are ledgers of failure. The creative writing life is one of pandering, rejection, graduate school debt, hustling at cocktail parties, and condescending emails from agents and editors.

Scratch does have one comfort, in that all its contributors have in one sense or another “made it,” at least enough to be asked to be included in this book. To the reader, their stories of squalor, crappy wine, mental health problems, and debt collectors all read romantic in hindsight, and the grind is glorious once that check finally does come through.