Not so long ago, television was seen as a boob tube for the drooling masses. But in what is widely referred to as a new Golden Age of television, the small screen is art. And how do we know it’s art? Just ask the people who make television.

Television has come a long way since 1961, when then-Federal Communications Commission chair Newton Minow characterized it as a “vast wasteland” full of “game shows, formula comedies about totally unbelievable families” and “most of all, boredom.” Today, quality television shows have ravishing cinematography, high production values, and top-flight talent—including movie stars like Jude Law in The Young Pope or Anthony Hopkins in Westworld.

Perhaps emboldened by their star power and critical acclaim, some quality television programs have gone one step further. Shows such as Westworld and Sherlock have plots that are thinly veiled metaphors for the awesomeness, depth, and moral complexity of quality television itself. In these shows, super-smart protagonists masterfully orchestrate complicated plots, dazzling lesser mortals and the viewing audience alike. You can practically hear the thump thump as the showrunners pat themselves on the back.

Consider “The National Anthem,” the first episode of the high-concept British anthology series Black Mirror, currently on Netflix. In a near-future Britain, an unknown, mysterious villain kidnaps the beloved people’s princess. As a condition of her release, her captor demands that the prime minister have sex with a pig on live television. At the end of the episode, we find out that the kidnapper was not a terrorist, but an artist. A newscaster notes that one art critic described the orchestration of the prime minister’s humiliation as “the first great artwork of the 21st century.”

“The National Anthem,” then, is a television show about a scandalous, dangerous, shocking television show. It uses the term “great artwork” with some irony, but this fact actually affirms its self-awareness—and therefore its status as intelligent and meaningful.

HBO’s Westworld is almost as blatant in its celebration of its own transcendent cleverness. The science fiction series is set in a futuristic Western theme park where visitors are encouraged to kill and fornicate with resident androids. The park is, therefore, violent, sexy adult entertainment, much like the violent, sexy adult entertainment for which HBO has become famous with shows like Game of Thrones.

The park is designed and run by Robert Ford, played by Anthony Hopkins doing his patented turn as a creepy genius. Ford is presented as an all-powerful manipulator. He murders those who threaten to expose his scheme, deceives his underlings and corporate bosses alike, and even replaces humans with robots, all in the interest of advancing his own complicated narrative. He’s also a stand-in for the showrunners themselves, who create tricky, interlocking plots for the viewer just as Ford creates a tricky, interlocking plot for his theme park visitors. Ford is compared repeatedly to God himself—which means that the showrunners of Westworld are fairly directly identifying themselves as deities. Television isn’t just art; it’s divine.

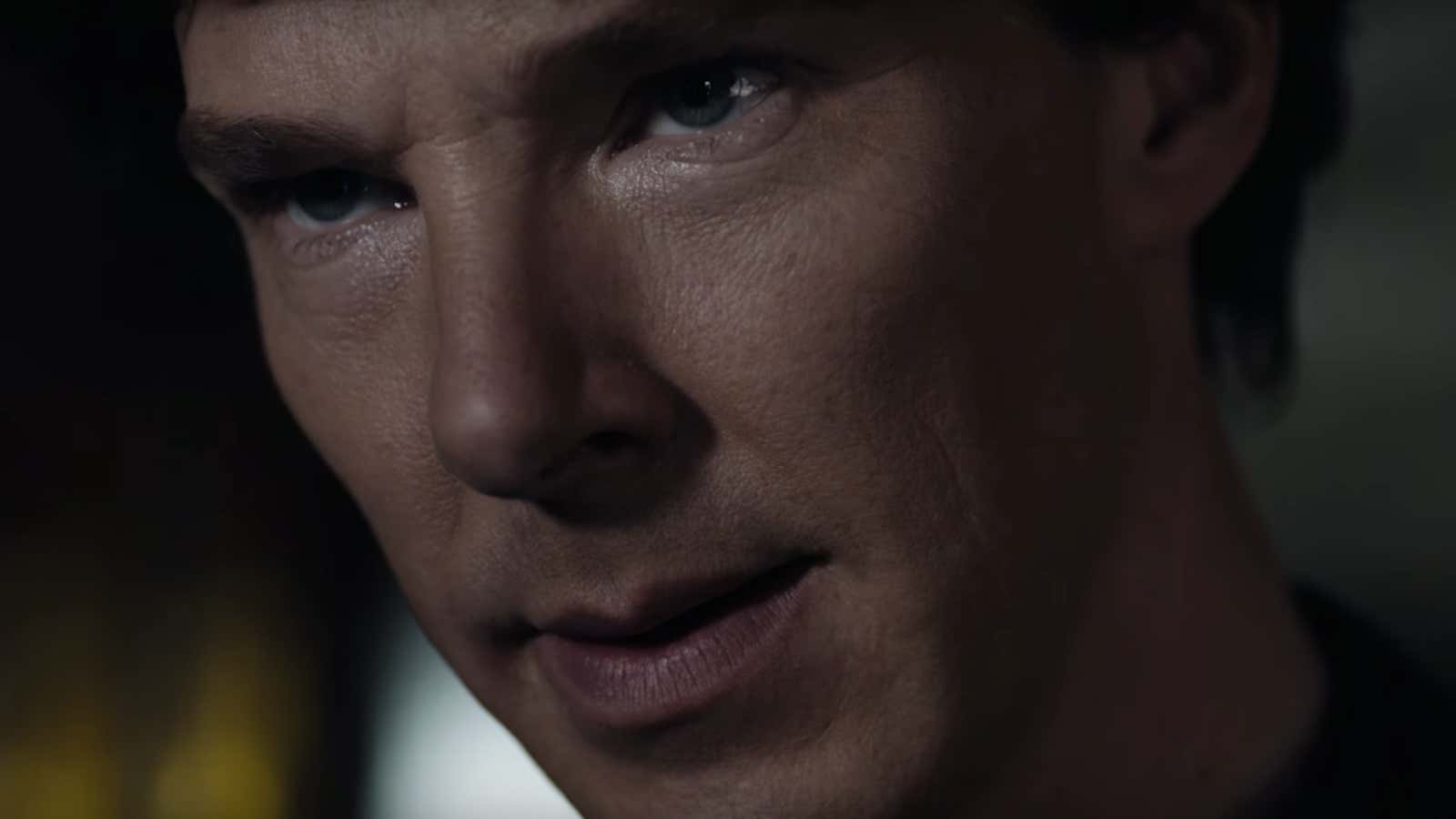

The BBC detective drama Sherlock, starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman, uses somewhat different methods to emphasize its cleverness. Instead of having a character stand for showrunner Steven Moffett, or create plots that mirror its own excellence, Sherlock producers love to layer powerpoint-like graphics with words and arrows over their crime scenes to show Sherlock’s thinking. This aesthetic meddling is as ostentatiously brilliant as the hero himself. Sherlock‘s recently completed season was particularly obsessed with its own genius, as the narrative cut back and forth between maybe-dream sequences and real action. Even Sherlock’s dog is not what it appears to be. Sherlock’s superintelligence is matched only by the superintelligence of his adversaries—and by the superintelligence of the show’s creators, who are constantly rubbing the viewer’s nose in all the clues they missed the first time.

In shows like Sherlock and Westworld, then, intricate storytelling is meant to signify depth and meaningfulness, as Elana H. Levine, coauthor of Legitimizing Teleivison told me by email. “It’s pretty common for these more aesthetically legitimated shows to also offer pretty convoluted kinds of storytelling, basically refusing to make it easy for a viewer to pop in and catch up right away,” she said. “Often the ‘answers’ to the mysteries or enigmas a program holds get held off until later episodes.”

Levine added that while quality television shows may “present this style of storytelling as sophisticated and requiring intellectual savvy to grasp,” the truth is that ” much less highly respected genres have been doing this for a long time—all kinds of mysteries, for example, as well as daytime soaps, which can drag out the answers and resolution to stories for months.” Indeed, shows like Westworld and Sherlock are so insistent on their own brilliance that it starts to come across as a little desperate. When Irene Adler (Lara Pulver) declares “Brainy is the new sexy” on Sherlock, you wonder if Moffat is reassuring his viewers, or himself, or both.

Great art shouldn’t have to keep nudging you to tell you how great and smart it is. Pride and Prejudice isn’t about how Elizabeth Bennett is a master manipulator who can only be understood by the most advanced readers. Singin’ in the Rain is about scrappily cobbling together art, not about the awesome spectacle of sweeping mastery. For that matter, Sesame Street, one of those old shows from back when everyone hated television, didn’t harp on its own genius. It just stood back and let Daveed Diggs or Stevie Wonder do their thing.

Today, practically everyone accepts that television is art, or that it can be. Yet it seems that doubts linger for television creators themselves. Why else should shows like Westworld and Black Mirror go out of their way to declare themselves works of complex genius? Television can be quality, no question. But a show in which showrunners spend whole episodes anxiously trying to prove their prowess to the audience isn’t great art. It’s just irritating.

Correction: A previous version of this post’s headline described season 4 as the series finale. It is the season finale.